How Did Pythagoras Influence Plato and the Neoplatonists?

Why did the Pythagorean communities die out?

How did Pythagoras and his followers find mystical truths in music and mathematics?

Did mystics from faraway India influence the Pythagorean and Platonic beliefs on reincarnation?

How similar were Pythagorean and early Christian monasticism?

Why did the Pythagoreans refuse to eat or touch beans?

BIOGRAPHY OF PYTHAGORAS

Pythagoras, born in Ionia, which is the Eastern Mediterranean coast of today’s Turkey, was both a philosopher and religious leader in the Greek settlements in Southern Italy in the sixth century BC, several centuries before Plato. Iamblichus, in his life of Pythagoras, calls him “leader and father of divine philosophy, “a god and demon,” or supernatural being, “or a divine man.” As a youth, he may have studied under Thales and the other Ionian Pre-Socratic philosophers. Diogenes Laertius says that he traveled abroad, visiting the Chaldeans, the Magi, and the Egyptians, initiating himself into the Greek and barbarian mysteries, learning the ancient Coptic language. He settled in Samos, Italy when he was forty.

Porphyry, in his Life of Pythagoras, says that “his speech was so persuasive that” “in one address in Italy he made more than two thousand adherents,” founding a community. “His ordinances and laws were by them received as divine precepts, and without them would do nothing. Indeed, they ranked him among the divinities. They held all property in common. Whenever they communicated to each other some choice bit of his philosophy, from which physical truths could always be deduced, they would swear by the” mystical number called the “Tetractys, adjuring Pythagoras as a divine witness.”

Many followers of Pythagoras lived in religious communities, as did the followers of Orpheus. For the Pythagoreans, philosophy was a way of life. Both these two sects influenced each other and ancient culture, exactly how is hard to say. The god Dionysius was worshipped in the Orphic cult.

Frederick Copleston, in his history of philosophy, notes that Orphic initiates “were also taught the doctrine of the transmigration of souls, so that for them it is the soul, and not the imprisoning body, which is the important part of man. In fact, the soul is the ‘real man,’ and it’s not the mere shadow-image of the body, as it appears in Homer.”

Robin Waterfield says that the elements of Orphism that the Pythagoreans adopted include the beliefs that:

- “The soul is imprisoned in the body until it has paid the penalty for past misdeeds.”

- “A life of ritual purity is required to cleanse our souls.”

- “Ascetic prescriptions for purity include abstention from blood sacrifice, and from eating meat and most fish.”[1]

The poet Xenophanes penned a poem about Pythagoras:

“One day, passing a puppy being thrashed,

Pythagoras pitied the whelp and cried out:

‘Stop! Don’t Strike! For it is the soul of a dear man,

I recognized him by his yelp.’”[2]

In a prior reflection by the Lutheran theologian Anders Nygren on Plato’s Symposium, he posits that there is a connection between the Platonic concept of divine love as described by Socrates’ lady friend Diotima in the Symposium and Orphism, which were early Greek religious practices surrounding the myth of Dionysus, according to the mythical poet Orpheus.[3]

Summary of Platonic Dialogues on Love and Friendship, With Commentary by Copleston and Anders Nygren

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/summary-of-platonic-dialogues-on-love-and-friendship/

https://youtu.be/cjXRXQc6Ff4

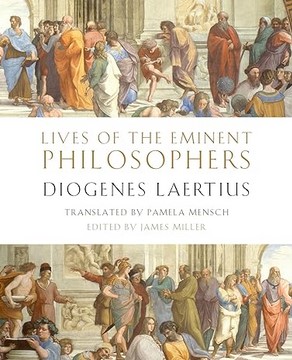

Frederick Copleston says that the three ancient biographies of Pythagoras are all romances, but that is misleading. Diogenes of Laertius likely wrote the famous Lives of Eminent Philosophers in the third century AD. Diogenes is a valuable source for the Greek philosophers, and for many he is the only source. He prefers to repeat interesting vignettes and stories about their lives rather than present a coherent summary of their philosophy, but often he is the only extant source.

Although they were written later in the fourth century AD, the two versions of the Life of Pythagoras, written by the Neoplatonists Porphyry and Iamblichus are more coherent, both as biographies and as summaries of their philosophies. Porphyry is best known for writing down the teachings of the eminent Neoplatonist Plotinus, his biography is much more succinct than the rambling, repetitive biography by Iamblichus.[4] But we must not forget that these ancient authors had access to sources that have since been lost in the sands of history.

MORAL LESSONS OF PYTHAGORAS

Iamblichus says that Pythagoras’ philosophy is primarily a moral philosophy that seeks, above all, to follow God,[5] which is also the goal of the Stoic and Platonic philosophies that draw from this tradition.

Iamblichus’ Pythagoras advises us to “arrange our whole life with a view to follow God.” Because “God exists and is the Lord of all things, it is universally acknowledged that good is to be requested of him.” “For all men do good to those whom they love, and to whom they are delighted.” Thus, we must live a godly life “in which God delights.”

Were the moral teachings of Pythagoras describing the type of henotheism that we see in the writings of the Greek and Roman Stoic philosophers? Like the Stoics, the Pythagorean works we reviewed do not dwell on the myths of the gods or refer to the various gods individually very often. Although the Pythagoreans often to refer to a singular God, or to the gods as a plural entity, they do not interchangeably speak of Zeus and God as the Stoics often do. This henotheism can be seen as an incipient monotheism. Although henotheism does not deny the existence of the pagan gods, they speak of them as if they had one voice.

Major Roman Stoic Philosophers, My Favorite Maxims: Epictetus, Rufus, Seneca & Marcus Aurelius

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/major-roman-stoic-philosophers-my-favorite-maxims-epictetus-rufus-seneca-marcus-aurelius/

https://youtu.be/E0qQgqGkoOE

Greek Stoic and Cynic Philosophers: My Favorite Maxims: Heraclitus, Antisthenes, Diogenes, and Zeno

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/greek-stoic-and-cynic-philosophers-my-favorite-sayings/

https://youtu.be/rq3oRftjM4c

Epictetus, Stoic Philosopher

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/epictetus-discourses-blog-1/

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/epictetus-discourses-blog-2/

https://youtu.be/Dhd543kov-E

Marcus Aurelius Blog 2, Others will be irritating, but not I!

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/marcus-aurelius-blog-2-others-will-be-irritating-but-not-i/

Marcus Aurelius Blog 3 Genuine Friends Don’t Keep Scorecards

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/marcus-aurelius-blog-3-genuine-friendships-have-no-scorecards/

Marcus Aurelius Blog 4 Be critical of yourself, be gracious towards your neighbor

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/marcus-aurelius-blog-4-be-critical-of-yourself-be-gracious-towards-your-neighbor/

Marcus Aurelius Blog 5 Seeing life’s misfortunes through the eyes of our neighbor

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/marcus-aurelius-blog-5-seeing-lifes-misfortunes-through-the-eyes-of-our-neighbor/

Marcus Aurelius: Meditations: Stoic View of Life

https://youtu.be/0qHpReZYhv4

Diogenes quotes Sosicrates: “Pythagoras said life resembles a festival, where some go to compete for a prize, others to buy or sell,” “while the philosopher hunts for the truth.”[6]

Iamblichus’ Pythagoras says that some men “are influenced by riches and luxury; others by love of power and domination; and others by an insane ambition for glory. But the most pure and unadulterated character is the man who give himself to the contemplation of the most beautiful things, and whom it is proper to call a philosopher.”[7]

Pythagoras taught the beautiful truth is that the “gods are not the causes of evil, and that diseases and calamities of the body are the seed of intemperance,” which is contrary to many myths.[8]

Diogenes’ Pythagoras says that “the soul of man is divided into three parts: mind, reason, and passion. Other animals have mind and passion, but man alone possesses reason.”

The Egyptians thought the brain was unimportant, and extracted it during embalming, but Pythagoras disagreed. “The soul’s headquarters extend from the heart to the brain: the part that resides in the heart is passion, while reason and mind are located in the brain. Sensations are distilled from these. Reasoning is immortal, the others are mortal. The soul draws its nourishment from the blood, and the ratios of the soul are breaths. The soul and its faculties are invisible, just as the ether is invisible.” [9]

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, we pray to God for guidance, or seek advice from our priest, pastor, or rabbi. But instead, Iamblichus’ Pythagoras encourages his disciples to consult someone “who has heard God himself, or procures it through divine art. Hence, the Pythagoreans studied the art of divination.”[10] Pythagoras himself never sacrificed animals, but he permitted his followers to “sacrifice animals, such as a cock or a lamb, or some other animal recently born,” but never oxen.[11] Would Pythagoras condone the examination of the entrails of sacrificed animals for messages from the gods, as was common in ancient Greece centuries later?

Porphyry explains that “Pythagoras instructed his disciples to speak well and think reverently of the Gods, muses and heroes, and likewise of parents and benefactors; that they should obey the laws; that they should not relegate the worship of the Gods to a secondary position, performing it eagerly, even at home; that to the celestial divinities they should sacrifice uncommon offerings; and ordinary ones to the inferior deities.”[12]

As a defender of paganism against Christianity, Porphyry urges his fellow pagans to worship the gods as fervently as Christians pray, that sacrifices alone are not enough. But traditionally, in paganism the proper form of the sacrifice was more important than the devotional motives of the devotee.

Diogenes Laertius cites the general principles of Pythagoras: “He forbids us to pray for ourselves, since we do not know what is good for us.” “One should be moderate when drinking or eating,” rejecting drunkenness. “Sexual pleasure is harmful in every season and not good for one’s health.”[13]

PYTHAGORAS ON GOOD AND EVIL, AND ON JUSTICE

Diogenes’ Pythagoras concludes that “the most important aspect of human life is the power to persuade the soul towards good or evil. Men who acquire a good soul are blessed,” while evil men “are never at rest,” nor can they keep to the narrow path. “Justice has the force of an oath, which is why Zeus is called the God of Oaths. Virtue is harmony and health and goodness in its entirety and God himself.” The universe is governed by “the laws of harmony. Friendship is harmonious equality.”[14]

Iamblichus explicitly states that Plato learned his concepts of justice as the first principle from the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras advises us that “association with men introduces justice, but alienation, and a contempt of the common man, produces injustice.” He extends this to friendly animals, urging that we can “neither injure, nor slay, nor eat any one of them,” since they, too, have rational souls.

Iamblichus’ Pythagoras warns us that since “want of riches sometimes compels many to act contrary to justice,” it is wise to live within your means. He also cautions that “insolence, luxury, and a contempt for the laws impels men to injustice.” He counsels that luxury be outlawed, and men be compelled to live “a temperate and manly life.” He proscribed his followers to establish governments that pass benevolent laws to promote justice, as “nothing is a greater evil than anarchy.” He suggests that men can be compelled to respect justice through fear, perhaps through judges, though he does not say how.[15]

Porphyry’s Pythagoras advises us: “There are three kinds of things that deserve to be pursued and acquired; honorable and virtuous things, those that” help us to live a godly life, “and those that bring pleasures of the blameless, the solid and grave kind, but not the vulgar intoxicating kinds. There are two kinds of pleasures: one that indulges the bellies and lusts by a profusion of wealth, which he compared to the murderous songs of the Sirens; the other kind consisted of things honest, just, and necessary to life, which are just as sweet as the first, without the need for repentance; and these pleasures he compared to the harmony of the Muses.”[16]

Pythagoras advises us “not to make enemies of our friends, but to make friends of our enemies. Regard nothing as your own, safeguard the law, and make war on lawlessness, and don’t destroy or injure plant life or any animal that does men no harm. He held that shame and discretion forbid indulgence in laughter or scowling.”[17]

We have an interesting reflection on whether Christians can laugh and joke, penned by St Nicodemus who famously compiled the Greek Philokalia. Although we do not agree totally with his advice, which was penned in a Greece surrounded by an overly strict Muslim culture, nevertheless it contains valid warnings of the spiritual dangers of mockery and satire.

St Nicodemus: Can Christians Laugh and Joke?

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/st-nicodemus-can-christians-laugh-and-joke/

https://youtu.be/WAroedUiytY

We can also question, in hindsight, whether Erasmus’ mocking and satirizing the corruption of the Catholic hierarchy in his witty work, In Praise of Folly, penned shortly before the Protestant Reformation, was beneficial or harmful to Christianity.

Did Erasmus’ On Praise of Folly Influence the Protestant Reformation?

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/erasmus-luthers-predecessor-the-praise-of-folly/

https://youtu.be/FYuIbYlIx5U

Porphyry repeats many of the pithy sayings of Pythagoras, with Porphyry’s interpretation of their meaning:

- “Do not poke the fire with a sword,” which means that “we ought not to excite a man full of fire and anger with sharp language. “

- “Do not pluck a crown, which means we should not violate the laws, which are the crowns of cities.”

- “Do not eat the heart, which means we should not afflict ourselves with sorrows.”

- “When starting a journey, do not turn back, which means that we should not regret this life when nearing our time of death.”

- “Do not walk in the public way, which means we should avoid the opinions of the multitude, adopting those of the learned and the few.”

- “Do not carry the images of the Gods in rings, which means that we should not reveal at once to the vulgar one’s opinions about the Gods, or discourse about them.”[18]

Porphyry’s Pythagoras counsels that “when we go to sleep,” “we should consider our past actions,” “and when we wake,” we should review with care our future plans. He repeats to himself before he falls asleep:

“Nor suffer sleep to close thine eyes

Till thrice thy acts that day thou hast run over;

How did I slip? What deeds? What duty have I left undone?”

On rising, Pythagoras repeats:

“When I wake, in order lay

The actions to be done today.”[19]

Many Stoic essays extol the heavenly pleasures of friendship and the qualities of a true friend. Diogenes’ Pythagoras said that “the possessions of friends are common property,” which was the practice of his followers, and that “friendship is equality.”[20]

Porphyry’s Pythagoras “loved his friends exceedingly, being the first to declare that the goods of friends are common, and that a friend was another self. While they were in good health, he always conversed with them; if they were sick, he nursed them; if they were afflicted in mind, he solaced them, some by incantations and magic charms, others by music. He had prepared songs for the diseases of the body, by the singing of which he cured the sick. He had also some that caused oblivion of sorrow, mitigation of anger and destruction of lust.”[21]

PYTHAGOREAN MONASTIC COMMUNITIES

Iamblichus describes how Pythagoras ministered to the students who joined his musical and mathematical monastic school of philosophy. Pythagoras sought to heal the souls of his followers through soothing melodies played on lyres.[22]

Iamblichus’ “Pythagoras encourages young men to the cultivation of learning,” saying it was “absurd to judge reason to be the most laudable of all things,” and yet spend little time studying, while they pay great “attention to the body, which is like a depraved friend who rapidly fails, while erudition, like worthy and good men, endures until death, and for some procures immortal renown after death.”[23]

The Pythagorean monastic ascetic practices are surprisingly similar to the seventh-century monastic practices of the early Egyptian desert monks as described by St John Climacus in his Ladder of Divine Ascent. One difference is that the early Christians did not emphasize the study of music and mathematics. Though these early Christian communities did not emphasize intellectual studies; nevertheless, all novices were expected to become literate so they could read the psalter.

John Climacus: First Step of the Ladder of Divine Ascent

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/st-john-climacus-first-step-on-the-ladder-of-divine-ascent/

https://youtu.be/Fco0W3bt5GA

Ladder of Divine Ascent, Remembrance of Death, Joy Making Mourning, and Despondency, Steps 6,7, & 13

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/ladder-of-divine-ascent-remembrance-of-death-joy-making-mourning-and-despondency-steps-67-13/

https://youtu.be/pFwC2nDf1CQ

St John Climacus on Gluttony and Fasting, Ladder of Divine Ascent, Step 14, and Eating for Health: DASH diet

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/eating-for-health-dash-diet-st-john-climacus-on-gluttony-and-fasting-in-ladder-of-divine-ascent/

https://youtu.be/KM0eMjE1fXc

St John Climacus on Love, Lust, and Marriage: Ladder of Divine Ascent, Step 15, on Purity and Chastity

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/st-john-climacus-on-love-lust-and-marriage-ladder-of-divine-ascent-step-15-on-purity-and-chastity/

https://youtu.be/YOlrP6-6YP0

Diogenes shares Pythagoras’ instructions for purification, some of which resemble the ancient Jewish laws. “Purity is attained by cleansing, ablution, and sprinkling with lustral water, and by avoiding all contact with cadavers, women in childbirth, and that defiles,” and beans and eggs and other forbidden foods.[24]

Diogenes’ “Pythagoras forbade the slaughter and eating of animals since their souls” also “possess justice. His real reason for forbidding the consumption of sentient animals was to train and accustom men to be content with their diet, so they could live on the most easily procurable foodstuffs, spreading their table with uncooked food and drinking only water.”[25]

Like later monastics, his initiates are not full-fledged members of the community, but are probationers when they first join. He speaks of quinquennial silence, which must mean that probationers must be silent for their first five years. They are not expected to share their property with the community until they are initiated as a full member. Like monks, they should be temperate in their behavior, avoiding anger and avarice. They are discouraged from sharing the order’s rituals with outsiders.[26]

In evaluating his newly admitted probationers, Iamblichus’ Pythagoras observed whether “they were able to refrain from speaking;” “whether they were modest;” whether they were driven by “immoderate passion or desire;” and whether they were capable of learning and memorizing, as a good memory is synonymous with intelligence in an oral tradition where all written works had to be copied.

Pythagoras evaluated whether they were obedient; whether they could “follow what was said, with rapidity and perspicuity;” and whether they showed a “certain love and temperance” in their studies. “He considered ferocity as hostile to such a mode of education. For impudence, shamelessness, intemperance, slothfulness, slowness in learning, unrestrained licentiousness, disgrace, and the like,” are characteristic of “savage manners.” Rather, he valued “gentleness and mildness.”

Iamblichus’ Pythagoras encouraged his students to learn how to be good leaders, “equal in all things to citizens, surpassing them in nothing other than justice,” which is a theme that Plato later adopts. Pythagoras also advises his students that they “should neither revile anyone, nor take vengeance on those who reviled them.”[27]

Iamblichus’ Pythagoras warns us: “Only a stupid man pays attention to the opinion of everyone,” “but it is also stupid to despise the opinion of everyone.” “Those young men who wish to be saved should listen to the opinions of their elders, and of those who have lived well.” “No man should be allowed to do as he pleases,” but should be obedient to the laws of a just government.[28]

The community members performed their tranquil morning walks alone, waiting to discuss their doctrines and disciplines later in the day. Although Pythagoras was himself a vegetarian, he did not forbid his disciples from eating the meat of animals that were noxious to the human race, which likely meant that they could only eat the meat of predatory animals. After all, an unfortunate relative may have been reincarnated as a cow or a goat, but if they were so objectionable that they were reincarnated as a wolf or a bear, then they were out of luck. For some reason, they did not eat fish. Those members who did not meet the ascetic or intellectual standards were expelled from the community.[29]

Like St Francis of Assisi, Iamblichus’ Pythagoras could reason with predatory beasts. “He detained the Daunian bear which had severely injured the inhabitants, and that having gently stroked it with his hands for a long time, fed it with maze and acorns, and compelled it by an oath no longer to touch any living thing, he dismissed it.” He also talked an ox out of eating beans, which was a foodstuff the Pythagoreans avoided.[30]

PYTHAGORAS, MUSICAL SCALES, AND MATHEMATICS

Copleston notes: “The religious-ascetic ideas and practices of the Pythagoreans centered around purity and purification, and the doctrine of transmigration of souls.” “The practice of silence, the influence of music, and the study of mathematics were all looked on as valuable aids in tending the soul.”

Aristotle, in his Metaphysics, observes that “the Pythagoreans devoted themselves to mathematics, they were the first to advance this study,” “and thought it contained the principles of all things.” Aristotle says, “since the Pythagoreans saw that the attributes and the ratios of the musical scales were expressible in numbers, and numbers seemed to be the first things in the whole of nature, then the whole heaven was like a musical scale and a number.”

Copleston notes: “To the Pythagoreans, not only was the earth spherical, but it is not the center of the universe. The earth and the planets, along with the sun, orbited round the central fire or ‘hearth of the Universe,’ which is identified with the number ONE.”[31] Porphyry notes that the Pythagoreans divided the world into “opposite powers; the ‘ONE’ was a better monad: light, right, equal, stable and straight; while the ‘OTHER’ was an inferior duad: darkness, left, unequal, unstable and movable.[32] Neoplatonists also view the Almighty, immovable God as the ONE, who perhaps corresponds to the Christian God the Father.

The Pythagoreans attached great mystical significance to the Tetractys, a triangle of ten points formed by ascending one, two, three, and four points. The Pythagoreans coined a prayer address to Tetractys:

“Bless us, divine number, you who generated gods and men! O holy, holy Tetractys, you who contain the root and source of the eternally flowing creation! For the divine number begins with the profound, pure unity until it comes to the holy four; then it begets the mother of all, the all-comprising, all-bounding, the first-born, the never-swerving, the never-tiring holy ten, the keyholder of all.”

The Pythagoreans saw the external world as expressions of numbers: ONE is a point, TWO is a line, THREE is a plane, and FOUR is a surface, which corresponds with our notion of dimensions. The Pythagoreans also associated other aspects of life with numbers, justice was assigned the number FOUR, and marriage FIVE, which is the sum of the even feminine number TWO and the odd masculine number THREE. The number four also corresponds to the four seasons, and to the ancient classical elements of air, fire, water, and earth. [33] Also, the proof of the Pythagorean theorem is attributed to the Pythagoreans, where a^2 + b^2 = c^2, where the square of the hypotenuse of a right triangle is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides.[34]

The lifeless boring manner in which most of us learned mathematics in school blinds us to the true elegance of mathematics. A brief foray into the puzzling world of recreational mathematics will demonstrate how mathematics can truly give us a glimpse into the mysterious cosmos that pervades our reality.

YouTube: Mathematics, Glimpse Into the Eternal, Plato, Meno, and Pythagoras

We also discovered that our favorite translator and commentator, Robin Waterfield, translated Iamblichus’ work on the Theology of Arithmetic. We are curious why Robin Waterfield was curious about this rather arcane work. Perhaps it is an ancient version of Martin Gardner’s Annotated Alice in Wonderland. If we find this interesting, we will cut a video on this sometime in 2025.

YouTube: Iamblichus, Theology of Arithmetic

We decided to reflect on how Pythagoras influenced Platonism after we reflected on the Platonic dialogue Meno, where Socrates led a slave boy into mathematically proving a simple geometry problem, ostensibly proving that knowledge can be remembered from a prior life.

YouTube: Meno

CONCLUSION

How did the Pythagoreans influence Plato? Copleston observes that “the Pythagoreans were certainly impressed by the importance of the soul and its right tendance and was one of the most cherished convictions of Plato, to which he clung all his life. Plato was also strongly influenced by the mathematical speculations of the Pythagoreans.”[35] In addition, Iamblichus specifically states that Plato adopted Pythagoras’ principal concern for justice.

DISCUSSION OF SOURCES

Before I researched this topic, I was under the impression that reliable sources on Pythagorean philosophy were scanty, but I was surprised by their depth. These ancient sources have their problems, as is typical, but they credibly describe in detail what life was like in a Pythagorean monastic community. Whenever possible, you should read the original works before drawing conclusions. Remember that when you read works penned by later historians or philosophers, you often learn more about them and their worldview than the history or philosophy they are depicting, which is why I prefer to heavily quote from the sources.

It is true that few, in any, writings directly by Pythagoras, have survived. None of his works listed by Diogenes Laertius have survived. Like Socrates, he may not have written down his teachings, relying on his disciples to transmit his knowledge. But we do know that Pythagoras had many enthusiastic disciples who spread his philosophy, quoting memories of what their beloved master taught them centuries before Plato. These later works could include quotations from Pythagoras, but we just do not know.

Pythagorean philosophy deeply influenced Plato, as he also believed in the transmigration of souls, or reincarnation. Socrates also adopted the ascetic attitudes of the Pythagoreans. There were many Neoplatonist philosophers who called themselves Pythagoreans. But why did the old Pythagorean schools die out long before the lifetimes of Socrates and Plato?

The Neoplatonist Porphyry himself speculates: “Pythagorean philosophy was enigmatic, and their commentaries were written in Doric, an obscure Greek dialect. These Doric writings were not fully understood, were misapprehended, and some were spurious.” The Pythagoreans affirm that Plato, Aristotle, and other philosophers appropriated the best of them, making but minor changes.[36]

Copleston glibly dismisses our three ancient biographies of Pythagoras as mere romances, one by Diogenes of Laertius, and two by the later Neoplatonists Porphyry and Iamblichus, who both used Diogenes as a source. Certainly, these works have problems, but the fact that these Neoplatonists were more interested in penning a moral hagiography of Pythagoras than an historical biography does not discredit their efforts.

But even with these problems, these Neoplatonist biographies include far too many historical details and details of the practices and the rules the Pythagorean communities followed to be deemed unreliable. Indeed, our Neoplatonists relied on now-lost works by several of Aristotle’s students, and they likely drew from original Pythagorean sources, now lost. In addition, there are numerous moral essays by other Neoplatonist Pythagoreans.

We purchased Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of Eminent Philosophers because it has excellent footnotes, plus half the book has many interesting scholarly essays on Diogenes and the ancient philosophers. You can purchase the Neoplatonist biographies for a reasonable price, but we did not since they were reproductions of what we found on the internet, with no additional footnotes.

Iamblichus’ Life of Protagoras

https://archive.org/details/b29318610/page/n7/mode/2up

Porphyry’s Life of Protagoras

https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/porphyry_life_of_pythagoras_02_text.htm

And we have book and lecture reviews on Greek History and Philosophy.

Book and Lecture Reviews of Ancient Greek History and Philosophy

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/book-and-lecture-reviews-of-ancient-greek-history-and-philosophy/

https://youtu.be/472aVKkPsk8

Although these biographies describe how Pythagoras quickly gained many adherents in many communities, positively influencing the various city-states to govern justly, they also describe intense political opposition his adherents faced. Pythagoras died an old man, in one account that Diogenes cites, he died a peaceful death, but in another account, he did not.[37]

It is undeniable that these Neoplatonists sought to bolster the pagan cause in an increasingly Christian world. Several miracle stories from Iamblichus mirror similar New Testament accounts, such as when a poisonous snake bit Pythagoras, but he bit back, killing the snake; and when witnesses heard a voice boom from above, “Hail Pythagoras.”[38]

One of the more fantastic stories was when the Tyrant Dionysius became angry when he could not befriend a group of travelling Pythagoreans. Dionysius dispatched thirty soldiers to fetch them. One couple was unable to keep up, straggling behind. Seeing the pursuing soldiers, the Pythagoreans determined that the precepts of their order permitted them to flee, but they encountered a field of beans, and since Pythagoreans should not even touch, let alone eat, beans, they halted, and were slaughtered by the soldiers.

The soldiers then remembered that their boss wanted them to bring back the Pythagoreans alive, so they brought these two straggling Pythagoreans, Myllias and his pregnant wife Timycha, before the Tyrant Dionysius. He offered to allow the couple to administer his kingdom. They refused, so the Tyrant queried if he could pose a question instead, and they agreed. He asked: Why did your companions avoid the field of beans?

Since Pythagoreans are not permitted to divulge information about their sect’s rituals to outsiders, this upset the pregnant Timycha so much that she bit off her tongue and spat it out at the Tyrant. The stated morals of the story are that it is challenging to keep your tongue in check, and that sometimes bad things happen to those with pure intellects.[39]

Why did the Pythagoreans abstain from beans? Aristotle speculates that this is because “beans resemble the genitals in shape, or because they,” having no joints, “resemble the gates of Hades, or because they ruin the constitution,” through flatulence, “or because they are oligarchic, since they are used to elect magistrates by lot.”[40] Porphyry speculates that a beans plant, when sprouting, resembles the head of an infant.[41] What we do know for sure is that the pregnant Timycha never revealed the secret behind the beans.

[1] Frederick Copleston, A History of Philosophy, Greece and Rome (New York: Image, Doubleday Books, 1962, 1993), Chapter IV, The Pythagorean Society, p. 29, and

Porphyry, Life of Protagoras, translated by Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie, 1920, Paragraph 20, from https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/porphyry_life_of_pythagoras_02_text.htm, and

Robin Waterfield, Pythagoras and Fifth-Century Pythagorism, included in The First Philosophers, The Presocratics and the Sophists, translated by Robin Waterfield (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, 2009), p. 88.

[2] Diogenes, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, translated by Pamela Mensch, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), Book on the Pythagorean Philosophers, Book 8.36, p. 410.

[3] Anders Nygren, Agape and Eros (New York, Harper & Row, 1969, 1958, 1938), Chapter 2-1, The Eros Motif, The Doctrine of Eros as a Doctrine of Salvation, pp. 160-165.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iamblichus

[5] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, translated by Thomas Taylor (London: AJ Valpy, 1818, originally 300s AD), Chapter XVIII, p. 63, from https://archive.org/details/b29318610/page/n7/mode/2up

[6] Diogenes, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book on the Pythagorean Philosophers, Book 8.8, p. 398.

[7] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, Chapter XII, pp. 38-39.

[8] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, Chapter XXXII, p. 155.

[9] Diogenes, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book on the Pythagorean Philosophers, Book 8.30, pp. 407-408.

[10] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, Chapter XXVIII, pp. 99-100.

[11] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, Chapter XXVIII, p. 109.

[12] Porphyry, Life of Protagoras, translated by Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie, 1920, Paragraph 38, from https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/porphyry_life_of_pythagoras_02_text.htm

[13] Diogenes, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book on the Pythagorean Philosophers, Book 8.9, p. 398.

[14] Diogenes, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book on the Pythagorean Philosophers, Book 8.32-33, p. 408.

[15] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, Chapter XXX, p. 122-130.

[16] Porphyry, Life of Protagoras, Paragraph 39.

[17] Diogenes, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book on the Pythagorean Philosophers, Book 8.23, p. 404.

[18] Porphyry, Life of Protagoras, Paragraph 42.

[19] Porphyry, Life of Protagoras, Paragraph 40.

[20] Diogenes, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book on the Pythagorean Philosophers, Book 8.10, p. 399.

[21] Porphyry, Life of Protagoras, Paragraph 33.

[22] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, Chapter XV, pp. 43-47.

[23] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, Chapter VIII, p. 27.

[24] Diogenes, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book on the Pythagorean Philosophers, Book 8.33, p. 408.

[25] Diogenes, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book on the Pythagorean Philosophers, Book 8.13, p. 401.

[26] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, Chapters XVII and XVIII, pp. 41-57.

[27] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, Chapter IX, pp. 29-32.

[28] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, Chapter XXXI, p. 142-144.

[29] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, Chapter XX, pp. 69-71.

[30] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, Chapter XIII, pp. 40-41.

[31] Frederick Copleston, A History of Philosophy, Greece and Rome, Chapter IV, The Pythagorean Society, pp. 29-37.

[32] Porphyry, Life of Protagoras, Paragraph 38.

[33] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetractys

[34] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pythagorean_theorem

[35] Frederick Copleston, A History of Philosophy, Greece and Rome, Chapter IV, The Pythagorean Society, p. 37.

[36] Porphyry, Life of Protagoras, Paragraph 53.

[37] Diogenes, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book on the Pythagorean Philosophers, Book 8.44-45, pp. 413-414.

[38] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pythagoras quoting from Walter Burkert, Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism, 1972, https://archive.org/details/lorescienceinanc0000burk/page/n9/mode/2up , the miracles are mentioned in Iamblichus’ work.

[39] Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras, Chapter XXXI, p. 136-140.

[40] Aristotle, On the Pythagoreans, fragment T10 in The First Philosophers, Pythagoras and Fifth-Century Pythagorism, p. 97.

[41] Porphyry, Life of Protagoras, Paragraph 44.

Be the first to comment