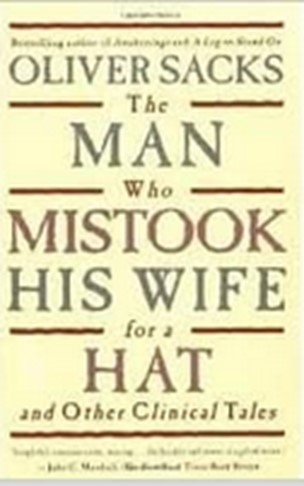

What can we learn from reflecting on the case studies of Phineas Gage and those included in Oliver Sacks’ book titled The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat?

To what extent should those suffering from certain mental illnesses and dementia be excused from also suffering the consequences of their actions?

Why was Phineas Gage arguably the most famous schmuck in history because of the horrific accident he suffered as a railroad worker in 1848?

What is it like to live your life unable to remember recent events, or remember who your loved ones are? Why do dementia patients often lash out at baffled bystanders, or even at those close family members who take care of them?

YouTubeScript with Book Links:

https://www.slideshare.net/BruceStrom1/man-who-mistook-his-wife-for-a-hat-sspdf

YouTube Video for this blog: https://youtu.be/tBZIs0YZ05A

HOW DID I BECOME INVOLVED IN SPREADING AWARENESS OF DEMENTIA?

How did I become involved in promoting awareness of dementia patients? I was involved in a controversy where I halted the foreclosure of an over-55 destitute condominium owner, who had advanced dementia, who had no close family, and who had fallen behind in his condominium maintenance fees. The foreclosure was halted so the court could appoint a guardian to place him in an appropriate care facility, and then pay off his back maintenance fees.

Why was everyone so upset? He had been harassing the people in the office. He had an alcoholic girlfriend, who moved out after his money ran out. There were numerous domestic disturbance calls to the police, and there were unconfirmed reports of him waving a gun around. His demented behavior was causing his neighbors to be quite upset, like it was his fault.

How I Halted a Foreclosure on a Destitute Owner with Advanced Dementia! We Discuss Dementia

The concept that someone could be so demented that they are no longer responsible for their behavior is hard for people to accept. After all, the concept that we are all responsible for our actions, that we always act out of free will, is a bedrock principle in our legal and even religious institutions. But unfortunately, as psychologists know, there are many mentally ill who cannot control their actions.

One early and famous case history is that of Phineas Gage, who is perhaps the most famous and influential schmuck in human history. I have listened to many psychology lectures in Wondrium, the Teaching Company, and university lectures on YouTube that retell the story of Phineas Gage, which I have heard a dozen times. When my daughter in medical school told me that she was starting her psychology section, I told her that she would soon hear the remarkable story of Phineas Gage.

Phineas Gage was working on the railroad one sunny day in September 1848. The gang he was directing had drilled a hole where a metal rod tamping iron was packing the powder and sand into the hole. He was distracted, and inadvertently positioned his head over the hole. As he opened his mouth about to speak, a spark ignited the powder, blasting the tamping iron behind his jaw and left eye, through his skull. The tamping iron landed eighty feet away, smeared with bits of blood and brain.

Remarkably, Phineas Gage never lost consciousness and was not in tremendous pain. He walked without assistance to an oxcart, in which he rode sitting upright to the doctor’s office half an hour away. He was vomiting and regurgitating blood, but the doctor patched him up, and he did live, although he had a very lengthy convalescence, he never suffered any extreme handicaps.

But the tamping iron did take out a big chunk of his cerebral cortex, the region of the brain that scientists have since determined governs our inhibitions. His behavior changed radically. Previously, Phineas Gage was a healthy, punctual, hardworking, conscientious twenty-five-year-old employee, who was the best foreman working for the railroad. After the accident, Phineas Gage started cursing, became rude and abrasive to his coworkers, and was unable to follow through on any planned activity. There were rumors that he started drinking and gambling and was guilty of inappropriate sexual behavior. These behavior changes, plus the inability to manage your financial affairs, are common markers for dementia today.

In time, often other portions of the brain can assume the functions of a damaged section. Dr Wikipedia reports that Phineas Gage may have recovered his ability to control his emotions a few years later. He emigrated to Chile, where he was able to hold a job driving a stagecoach, before passing about a decade after his accident when he was thirty-six. It is indeed remarkable that he could function somewhat normally after such a devastating trauma to his brain.

Did that tamping iron take out that part of Phineas Gage that controlled his moral compass? The testimony of his associates and medical experts of the time would agree, though it seems that in time his brain rewired and recovered at least some of this compass.

Can dementia rob those with advanced dementia of their moral compass? I did not ask, DOES dementia rob some of their moral compass because, unlike the sudden accident of Phineas Gage, dementia is gradual at first, and does not really change the personality of the patient, but rather accentuates their existing personality. Someone who begins with a strong moral compass will likely retain more of their compass as their dementia progresses.

But there is a caveat: we must also emphasize that many dementia patients do lash out as their dementia progresses, mostly out of frustration, and in response to pain and discomfort they experience because they are not eating well, or able to take care of themselves, or perhaps have a urinary tract infection, including many who wound have never struck out before their dementia. The irrational behavior of those suffering from dementia is such a problem that a page on the Alzheimer’s Association website discusses why those with dementia also often suffer from aggression and anger, and how to deal with it.

This means that whenever someone is seventy or older, or sometimes younger, lashes out inappropriately, or behaves in a sexually inappropriate manner, even if that has always been part of their personality, you can never rule out that they are suffering from the early stages of dementia. You have to show patience towards our elderly citizens, you have to give them a break.

And we always repeat that there is a rare type of dementia that is curable, and that tumors or other metabolic or medical disorders can cause symptoms that mimic dementia, so it is critical that the elderly are seen by doctors, and that their doctors be completely informed about all the health challenges they face. And also fill up the grocery bag with all their medications to make sure that combinations of drugs are not causing problems.

THE MAN WHO MISTOOK HIS WIFE FOR A HAT

One book that was continually mentioned in the footnotes was Oliver Sacks’ The Man Who Mistook His Wife For a Hat, which is a remarkable collections of case histories of patients with puzzling, remarkable, and often tragic neural deficits of the brain. Many of his patients were in a home for the aging, but he did not report any cases that were obviously dementia, as they did not seem to have the relatively quick deterioration that dementia patients suffer. But they do illustrate the persistent inability of these patients to control their behavior, their inability to better themselves by simply trying harder, and their persistent helplessness in the face of their mental conditions.

One curious story was the case of the man who mistook his wife for a hat. Dr P. was a well-known musician, known as a singer, then as a music teacher, but as he aged a curious deficit evolved. He lost the ability to recognize faces, but when they began to speak, he could identify them by their voice. He could converse without difficulty and intelligently. He did not feel ill, and he was a dazzling singer, much like Glen Campbell and Tony Bennett who did not lose their ability to perform until very late in the course of their dementia.

What was wrong? He went to see an ophthalmologist to check his eyesight, but there was nothing wrong physically, so he was referred to Dr Sacks, a neurologist. He performed a reflex test, and afterwards discovered he did not know how to put his shoe back on! The good doctor had to help him put on his shoe, and then asked him to describe pictures in a National Geographic magazine. He could describe this detail or that but found that he had lost the ability to describe the landscape as a whole!

When the examination was over, Dr P. “looked around for his hat. He reached out his hand and took hold of his wife’s head, tried to lift it off, to put it on. He had apparently mistaken his wife for a hat! His wife looked as if she was used to such things.”

Later, our good doctor visited his house. Dr Sacks remembered, “On the walls of his apartment were photographs of his family, his colleagues, his pupils, and himself.” “By and large, he recognized nobody: neither his family, nor his colleagues, nor his pupils, nor himself. He recognized a portrait of Einstein because he picked up the characteristic hair and mustache; and the same thing happened with one or two other people.”

Although he could distinguish the stylized pictures of royalty on the playing cards, or maybe he saw the letters J-Q-K. Also, he could not make sense of what was happening in a movie playing on the television. Dr P also reported that he could no longer dream pictorially, and his wife said he could only perform daily tasks if he sang while doing them. The visual cortex of his brain suffered damage, his brain could interpret sounds, but not sight.[1]

HEALING QUALITIES OF MUSIC AND PERFORMING

In addition to this case of Dr P, the music teacher, Dr Sacks has several case histories where music can stimulate many who suffer from neural deficits. Dr Sacks states that even the profoundly retarded can seemingly come alive when exposed to music: “Their uncouth movements may disappear in a moment with music and dancing. Suddenly, with music, they know how to move. We see how the retarded, unable to perform fairly simple tasks involving perhaps four or five movements of procedures in sequence, can do these perfectly if they work to music.” “What we see, fundamentally, is the power of music to organize, and to do this efficaciously, as well as joyfully, when abstract or schematic forms of organization fail.”[2]

In our review of books about Alzheimer’s, the best case study we have found is that of the biography of Glen Campbell’s latter life by his fourth wife and widow Kim, which shows both how his personality slowly transitioned into dementia, and how music and his musical performances appeared to slow his descent into advanced dementia.

Glen Campbell Suffering from Alzheimer’s, Early Signs and Symptoms

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/glen-campbell-suffering-from-alzheimers-early-signs-and-symptoms/

https://youtu.be/F9NmDiiPowI

Both Glen Campbell and Tony Bennett had a final performance, sharing with the audience that they were indeed suffering from Alzheimer’s. Tony Bennett’s last performance included duets with Lady Gaga, who was his New York neighbor and who often visited his studio to practice their duets. Both these musicians had little difficulty performing their old songs with panache, but had great difficulty performing new songs, though a teleprompter helped some.

Likewise, Rita Hayworth also continued her acting career through the earlier stages of her Alzheimer’s, and her performance helped her dementia to subside, though she found it increasingly difficult to remember her lines.

Tony Bennett and Rita Hayworth: Their Struggle With Alzheimer’s

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/tony-bennett-and-rita-hayworth-their-struggle-with-alzheimers/

https://youtu.be/4ujlV3a7Il8

Dr Sacks has a touching story about Rebecca, who was profoundly retarded from birth, unable to walk around the block, clothed herself with difficulty, and was unable to unlock her door with a key. The rituals, the candles, and the bowing in her Orthodox Jewish services brought her comfort, but she did not perform well in the workshops and odd jobs that were intended to give her focus. But she loved to perform in a special theater group. Dr Sacks remembers, “She loved the theater group, it composed her. She did amazingly well: she became a complete person, poised, fluent, with style, in each role. If you saw Rebecca on the stage, for this theater group became her life, one would never even guess that she was mentally defective.”

Dr Sacks concludes, “We pay far too much attention to the defects of our patients, as Rebecca was the first to tell me, and far too little to what was intact or preserved.”[3]

This same concept that rather than trying to improve dementia patients, in a foolish attempt to make them normal again, we should rather seek to encourage and enhance those joyous activities and capabilities they have remaining, is a theme both in the prior videos we discussed, but also in the wonderful book by Joanne Koenig Coste, Learning to Speak Alzheimer’s. She not only cared for her husband who suffered from early onset dementia, but also cared for many dementia patients in a facility for many years after his death.

Learning To Speak Alzheimer’s and Dementia Caretakers Guide

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/learning-to-speak-alzheimers-a-caretakers-guide/

https://youtu.be/9vPK05gs8BQ

AMNESIA FOR JIMMY MEANT HARRY TRUMAN WAS PRESIDENT FOREVER

Jimmy G was admitted to the nursing home where Dr Sacks was in attendance in 1975, he had a severe case of retrograde amnesia. Jimmy remembered his wartime experiences like they were yesterday. He enlisted in the Navy when he was seventeen in 1943, and by 1945 America had just won the war, FDR had died at Warm Springs, and Harry Truman was giving the Russians hell. When he first examined him, our good doctor made the mistake of showing Jimmy his face in the mirror. He panicked! Who was that grey-haired man? He knew he was all of nineteen years old!

Jimmy was looking forward to attending college on the GI Bill, he was proud that his older brother was studying accounting and would soon get married. Dr Sacks obtained his records from the Navy, he was discharged in 1965, but found his way to Bellevue Mental Hospital in 1971, where his heavy drinking and cirrhosis of the liver led to a diagnosis of “advanced organic brain-syndrome.” He was dumped in a substandard nursing home until he was transferred to Dr Sacks’ nursing home.

Jimmy could converse in witty conversation, he could play a good game of checkers, but did not have the attention span for chess, and he performed well on cognition tests. They contacted his brother, they discovered they had not been in contact for thirty years, his brother said his drinking became uncontrollable after he retired from the Navy. They convinced him to visit Jimmy in the hospital, but that only made him angry. In a deep sense, he recognized his brother, but he was so angry. Who was this strange, unsettling fifty-year-old man? His real brother was only twenty-one!

Was his amnesia caused by his drinking, or did he drink to crowd out his creeping amnesia, or did they feed on each other? We learned that Rita Hayworth also was drinking heavily in her early years of dementia. We can ask the same question of her, did her drinking worsen her dementia, or did she drink because of her dementia, or both? Dr Sacks does say that on rare occasions heavy drinking can contribute to amnesia. Likely the medical records that would answer that question do not exist.

Jimmy, like many with dementia, only remembers the past, he remembers nothing of recent experiences. Unlike dementia patients, his condition did not deteriorate rapidly. He could cope in the hospital from day to day, although like some dementia patients, seeing his image in a mirror upset him, as it caused a conflict between his self-image in his mind and his actual appearance.[4]

Dr Sacks describes another case of another frenetic patient who had no short-term memory whatsoever, forgetting names and people. He remembers that “Mr Thompson would identify me, misidentify, pseudo-identify me, as a dozen different people in the course of five minutes. He would whirl, fluently, from one guess, one hypothesis, one belief, to the next, without any appearance of uncertainty. He never knew who I was, or what and where he was: an ex-grocer, with severe Korsakov’s Disease, in a neurological institution.” He told “amazing personal stories full of fantastic adventures.”[5]

OTHER VIDEOS AND BLOGS

We also reviewed an even more enlightening collection of case histories of both dementia patients and their caretakers, which helps alleviate the guilt many caregivers feel when they react negatively to the dementia displayed by their loved ones. Caregivers are discouraged when their efforts are not appreciated by the loved ones they care for, because their dementia has either robbed them of the compassion they once felt or made their remaining compassion fleeting and fickle.

Problems Family Caretakers Face When Caring for Loved Ones Suffering From Dementia

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/problems-family-caretakers-face-when-caring-for-loved-ones-suffering-from-dementia/

https://youtu.be/VqR7y0Z8bYk

Many police departments, particularly in my state, Florida, have CIT police training programs through NAMI which cover mental illness, but currently these only cover autism, drug abuse issues, and mental issues with younger offenders. But we do know that there are discussions between the Alzheimer’s Association, NAMI, and the police departments locally to address this training issue, and perhaps nationally as well.

Wellness Checks for Dementia: Police and Mental Illness

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/wellness-checks-for-dementia-police-and-mental-illness/

https://youtu.be/z_SlPLARCxU

DISCUSSING THE SOURCES

Oliver Sacks’ wonderful book, the Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, is one of those rare books that both clinicians and laymen can benefit from reading and is cited by many other books and studies. There is a hundred-page book that analyzes further these case histories, and that itself has close to five thousand citations. The review states that Dr Sacks found it puzzling why so many doctors preferred an impersonal approach to their patients. “His ideas were so influential that they heralded the arrival of a broader movement – narrative medicine – that placed stronger emphasis on listening to and incorporating patients’ experiences and insights into their care.” [6] The original copyright was in 1970, it paralleled the anti-psychiatry movement that sought to humanize the mentally ill patient and give him as much agency as possible.

This book has twenty-four case studies that have fascinated clinicians. They include a case where a patient cannot recognize anything on the left side of her body, or even her plate at mealtime,[7] a patient whose drug use caused an extremely heightened sense of smell,[8] and an autistic artist who could draw amazingly expressive illustrations with just a little encouragement.[9]

He explored patients with Tourette’s Syndrome, which “is characterized by an excess of nervous energy,” with “strange motions and notions: tics, jerks, mannerisms, grimaces, noises, curses, involuntary imitations and compulsions of all sorts.”[10] He examined several cases of Parkinson’s, a gradual neurological disease. Patients first experience tremors and difficulty walking, and as the disease slowly progresses, symptoms of dementia manifest. In one case a patient leaned a good twenty degrees when he walked.[11]

We have learned in our studies that sometimes a brain tumor can cause dementia-like symptoms, and if the tumor can be removed, the dementia dissipates. Oliver Sacks explored several cases of patients suffering brain tumors, sometimes they cause changes in behavior, such as when one droll chemist became funny, impulsive, and superficial.[12] An Indian patient had a malignant brain tumor that could not be removed, her tumor caused vivid technicolor memories of the Indian landscape, villages, homes, and gardens from her childhood. As death approached, these pleasant memories flooded over her that lasted most of the day.[13] He examined cases where strokes also caused hallucinations, as in the case of an Irish lady whose stroke triggered songs she had heard in her childhood.[14]

Oliver Sacks also ponders the visions of the influential Hildegard of Bingen, the mystic who so profoundly influenced medieval Catholicism. He examines her illustrations of many of these visions, saying that they indisputably resemble hallucinations caused by visual auras of migraines. Hildegard herself writes: “The visions which I saw beheld neither in sleep, nor with my carnal eyes, nor with the ears of the flesh, nor in hidden places; but wakeful, alert, and with the eyes of the spirit and the inward ears, I perceive them in open view and according to the will of God.” “I have never fallen prey to ecstasy in the visions, but I see them wide awake, day and night.”[15] This scientific observation should not damage the faith of anyone, for when God does bless a saint with visions, he would then cause their senses to perceive the visions.

[1] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 1, pp. 8-22.

[2] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 21, pp. 185-186.

[3] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 21, pp. 178-184.

[4] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 2, pp. 23-42.

[5] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 12, pp. 108-110.

[6] https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781912282548/analysis-oliver-sacks-man-mistook-wife-hat-clinical-tales-dario-krpan-alexander-connor

[7] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 8, pp. 77-79.

[8] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 18, pp. 156-159.

[9] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 24, pp. 214-233.

[10] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 10, p. 92.

[11] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 7, pp. 71-76.

[12] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 13, pp. 116-119.

[13] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 17, pp. 153-155.

[14] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 15, pp. 132-134 and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hildegard_of_Bingen

[15] Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Chapter 20, pp. 166-170.

2 Trackbacks / Pingbacks