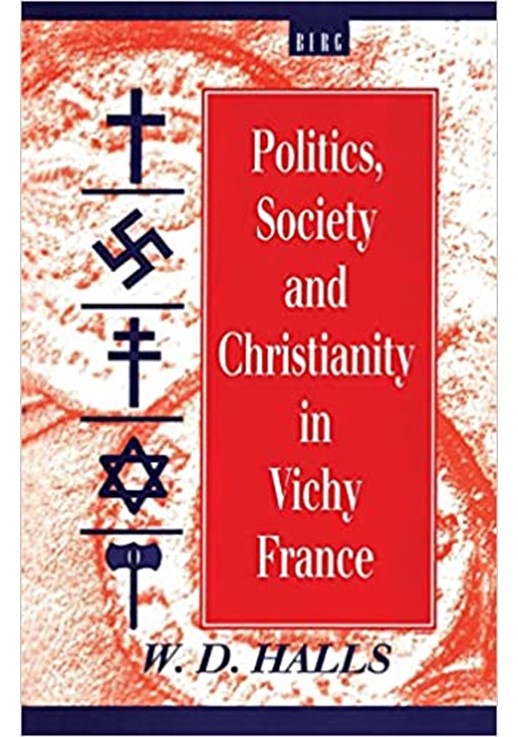

When reviewing the book, “Politics, Society and Christianity in Vichy France,” we realize that the reactions by French Christians to the calamity of the German invasion are a reflection of the reactions of the French people as a whole. In the early years the war seemed to be over soon after it started, nobody could imagine that the German army could be dislodged from Europe proper, everybody supported Marshal Petain and the Vichy regime, everyone wanted to blame the success of the German invasion on the moral weakness of the old French Republic, nobody was eager to fight a guerilla war on French soil where the Nazis could bring vengeance on their wives and children.

Blog 1 of this series: http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/vichy-france-regime-blog-1-pro-life-pro-catholic-and-fascist/

Blog 2 of this series: http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/vichy-france-blog-2-collaborating-with-the-germans-in-the-early-years-1940-1942/

Blog 3 of this series: http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/vichy-france-blog-3-the-tide-turns-resistance-and-collaboration/

Hitler shrewdly allowed the rump Vichy regime nominal autonomy in the third of France that was unoccupied by German troops. Marshal Petain and the Vichy regime had moral legitimacy in the early years of the war. Since the church teaches that the political authorities should be respected, the regime had the support of the elderly bishops throughout the war. The British were urging the French to fight on, from North Africa if necessary, but the Church Hierarchy felt that an attitude of repentance and acceptance was more appropriate. The humiliation of the German conquest was seen as an opportunity for moral and religious transformation.

France at the start of the war was becoming more and more secular, although 80 per cent were nominally Catholic, only one in three attended Mass at Easter. Mostly women and children attended Mass regularly. In 1940 the clergy was aging; forty percent were over sixty, although many younger priests answered the call to the priesthood during the war. The French state became more hostile to religion, religious property was seized, religious orders had their schools closed and had to be approved by the state, and the state no longer paid the clergy.[1] The Protestant pastors tended to be younger and more active in the Resistance, I part due to the fact that they were more numerous in the mountainous Vichy regions of France. The Vichy regime reversed some of this anti-clerical legislation, and some of this legislation survived when France was liberated.

Like the general population, some of the clergy were collaborators, some aided the Resistance. At the beginning of the war the godless Communists were seen as the enemy, and as the fascists in the recently concluded Spanish Civil War sided with the Catholics in opposing the Communists, many Catholics initially supported the fascists. Also, many Catholics were anti-Semitic, we discussed the role of the Dreyfus affair in shaping French culture in an earlier blog. Many Catholics did not turn away from fascism even in the face of the continuing brutality of the German occupation, many of the French who joined the Milice, the French version of the Gestapo with an even worse reputation, considered themselves hard core Catholics. Many Catholics volunteered to fight in the French Volunteer Legion, or LVF, who fought the Communists on the Eastern Front. They saw themselves a participating in a Christian Crusade against Bolshevism, delivering France from the clutches of the Jews. Both of these organizations had Catholic chaplains.[2]

The abhorrent treatment of the Jews was what turned much of the clergy and the faithful against the regime. Several bishops protested against the treatment of the Jews while they continued to support Petain.[3] Many Catholics and Protestants clergy and faithful cooperated in actively resisted the Nazi persecution of the Jews.

Many seminaries, convents and churches hid Jews, often with secret cooperation from bishops and other church administrators, many of the faithful helped Jews escape to Spain and Switzerland. Nuns in Lyons became specialist in forging identity papers to help Jews escape. Laval once had ordered the deporting of Jewish children, they were snatched from a train station and hidden in seminaries and convents. The Germans were furious at clerical intervention in their plans to exterminate the Jews.[4]

In the end the Church gained little from the efforts of the Vichy regime, upon its liberation France reverted back to a secular state, and the constant battle between clericalism and anti-clericalism was resumed. The authority of the bishops, who were so closed tied to Marshal Petain and the Vichy regime, was undermined, most bishops were forced into retirement. Much of the Vichy legislation was declared null and void, although the Vichy bureaucracy was allowed to continue governing. Some measures were retained, the religious orders continued to be teachers, the subsidies paid to Catholic schools were not revoked. The experience of the Resistance may have helped the new worker-priest movement grow, younger priests wanted to be closer to the working class. The adversity of the war had encouraged a revival among many faithful.

How did the experience of the faithful affect the sessions of the second Vatican Council? The war years brought more denominational mixing, the Dachau prison camp was an ecumenical brotherhood, where French priests and protestant pastors and Jews all suffered together for their faith. The experience of Yves Congar in a French POW camp influenced his later ecumenical theology. Likewise, Catholics and Protestants cooperated in the Resistance movements.[5] Definitely after the war and the Holocaust purged anti-Semitism from the hearts of the truly faithful, and the Vatican II decrees on ecumenicism peaceful coexistence with Jews were directly influenced by these wartime experiences.

The greatest effect of the war experiences was the realization that Democracy was the most desirable political system for not only tolerating but encouraging the faithful in their desire to live a godly life, bringing up their children in the faith. The Vichy government may have been seen as the defender of ancient virtue in the early years of the occupation, but it was all too eager to collaborate with the evil Nazi occupiers in the vain and futile hope that order would be maintained. All who survived the war realized that totalitarian governments would in the end be inimical to the Christian faith, freedom was seen as a Christian virtue. The greatest lesson was that the Catholic Church needed to be on the side of virtue on issues that affect social justice.

Click here for another blog which compares Trump and his politics to the situation in Vichy France.

[1] WD Halls, “Politics, Society and Christianity in Vichy France”, (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 1995), pp. 9-15.

[2] WD Halls, Politics, Society and Christianity in Vichy France, pp. 346-351.

[3] WD Halls, Politics, Society and Christianity in Vichy France, p. 75.

[4] WD Halls, Politics, Society and Christianity in Vichy France, pp. 136-139.

[5] WD Halls, Politics, Society and Christianity in Vichy France, pp. 384-387.

4 Trackbacks / Pingbacks