We have listened to many histories of the American Civil War, but how did the ordinary soldiers and generals view this conflict that so deeply shaped American and world history?

We reflect both on the memoirs and correspondence of Generals Grant and Lincoln, as well letters of ordinary soldiers writing home, describing the long struggle by the Union to capture the last major stronghold on the mighty Mississippi River, Vicksburg in Mississippi.

See our prior reflection for a broad overview of the Civil War through paintings, and some interesting photographs of Civil War forts in Georgia and Florida.

Civil War Through Paintings

https://youtu.be/2hoBOSOBUP8

BACKGROUND LEADING UP TO SIEGE OF VICKSBURG

Many citizens in both North and South thought the Civil War would be a short conflict, but military strategists feared a protracted struggle. Foremost among them was General Winfield Scott, a brilliant strategic general and hero of the Mexican War who served under seven Presidents. However, by the 1860’s he was in his seventies and was so obese that he had to be hoisted on and off his horse with a crane.

But Scott was still a sharp general, and his “Anaconda Plan” was the strategy that would win the war for the Union. This Great Snake picture was printed in the newspapers across the country in 1861. This plan called for a naval blockade that strangled the commerce of the Confederacy, the Union forces seizing control of the Mississippi River, and Union forces marching through the heart of the Confederacy.

There were roughly two theaters of War, the Eastern Theater where Confederate Generals, in particular Robert E Lee, often bested Union generals in early battles in Virginia and surrounding states, and the Western Theater where the Union forces were victorious from the beginning in their struggle to seize control of the Mississippi River basin. But the battles in the Eastern Theater were more visible to newspapermen and foreign diplomats.

As horrific casualties mounted for both sides, the Civil War became unpopular in the North, and although the Republicans did not lose control of Congress in the 1862-63 midterm elections, their margin in the House was greatly decreased. Abraham Lincoln began to have serious doubts about whether he would win the upcoming 1864 Presidential Election.

In July 1863 the Union won two key battles that started to turn the tide of war in favor of the Union. The Confederate General Robert E Lee invaded Pennsylvania at Gettysburg, desperately seeking an offensive win to legitimize the Southern cause to potential allies in England and France. In the bloodiest battle of the Civil War, Robert E Lee was defeated, but the overcautious General Meade failed to pursue him into Virginia.

Also in July 1863, General Grant won the Siege of Vicksburg, which enabled the Union gunboats to control the entire Mississippi River, cutting the Confederacy in two. After this battle, finding a general who relentlessly pursued the enemy forces, Lincoln promoted General Grant to command all the Union armies.

EVENTS BEFORE THE SEIGE OF VICKSBURG

Initially, General Halleck was placed in charge of the Union forces in the Western Theater. Although he was a competent bureaucrat, he was not an effective field commander. Rather than give succinct orders to his subordinates, he instead gave them vague suggestions. Ulysses S Grant took advantage of these opportunities, winning many battles, earning many promotions, persevering in difficult battles like Shiloh where the Confederates initially had the upper hand.

Union forces had already captured New Orleans at the mouth of the Mississippi, and General Grant had won many battles gaining control of the upper Mississippi. The major Confederate fort remaining on the Mississippi was Vicksburg, about fifty miles west of the Capitol of Mississippi, Jackson. The problem was that Grant’s armies were far from the Union supply lines in Memphis, Tennessee, which was over two hundred miles north of Vicksburg.[1]

In his memoirs, General Grant remembers: “Up to this time it was an axiom in war that large bodies of troops must operate from a base of supplies which they always covered and guarded in all forward movements.” Grant had ordered that the army forage for supplies at the beginning of his Vicksburg campaign, he noticed that “the stock was bountiful,” “it gave me the idea of the possibility of supplying a moving column in an enemy’s country from the country itself.” A footnote posits that it was not entirely Grant’s idea, General Halleck had also suggested it.[2]

His friend and subordinate General Sherman thought it would be too risky to advance on Jackson, and then to Vicksburg, that it would be wiser to approach from the north, keeping a secure supply line in his rear. But General Grant was willing to take risks to gain an advantage.

General Grant remembers: “The North had become very much discouraged. Many strong Union men believed that the war must prove a failure. The elections of 1862 had gone against the party which was for the prosecution of the war to save the Union if it took the last man and the last dollar. Voluntary enlistments had ceased through the greater part of the North, and the draft had been adopted to fill up the ranks. It was my judgment at the time that to make a backward movement from Vicksburg to Memphis, would be interpreted, by many of those yet full of hope for preservation of the Union, as a defeat, and that the draft would be resisted, desertions ensue, and the power to capture and punish deserters lost. There was nothing left to be done but to go forward to a decisive victory.”[3]

General Grant decided to take the risk of having federal gunboats and troop transport ships run the gauntlet past the formidable Confederate batteries on the Mississippi shores of Vicksburg on April 16, 1863. These ships hugged the shore when the Union forces observed that the Confederate cannons could not point down readily. After that, Grant’s troops quickly marched on General Johnston’s position near Jackson, living off the land, preventing him from joining forces with General Pemberton’s forces, who then pulled his forces into the town and fortifications of Vicksburg. The many battles and maneuvering before the siege of Vicksburg were like a long chess game, which we are vastly oversimplifying.

Professor Gallagher says, “Grant’s Vicksburg campaign ranks among the most brilliant in American history. He abandoned his supply lines in moving east towards Jackson,” his army living off the land, capturing food and livestock from the farms they encountered. “He marched quickly and defeated the enemy in detail,” not giving the Confederates time to consolidate their forces, “capturing a 30,000-man army and vast Confederate military material. His victory achieved one of the North’s major strategic goals.”[4]

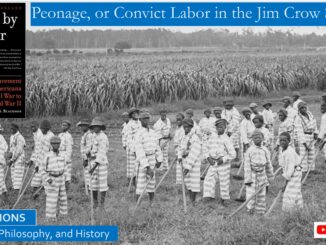

FREEDMEN’S BUREAU IS BORN, NEGRO SOLDIERS

After the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, runaway slaves were flocking to Union lines in ever greater numbers, and many were permitted to work and sometimes fight in the Union Army. These wartime experiences changed many Northerner’s opinions about the freed slaves. Conditions in the field during the Vicksburg campaign gave rise to the idea of the Freedmen’s Bureau assisting the freed slaves. Runaway slaves flocked to the Union lines by the thousands.

General Grant remembers: “Orders of the government prohibited the expulsion of the negroes from the protection of the army.” “Humanity forbade allowing them to starve.” “There was no special authority for feeding them unless they were employed as teamsters, cooks and pioneers with the army; but only able-bodied young men were suitable for such work.” But “the plantations were all deserted; the cotton and corn were ripe: men, women and children above ten years of age could be employed in saving these crops. To do this work with contrabands,” “organization under a competent chief was necessary.”

The army paid for the contrabands, or runaway slaves, to pick the cotton and harvest the crops, selling it up north. “In this way, a fund was created not only sufficient to feed and clothe all, old and young, male and female, but to build them comfortable cabins, hospitals for the sick, and to supply them with comforts they had never known before.”[5]

General Sherman was not enthusiastic about negroes assisting in the war effort, he wrote to his brother in April 1863: “The Union companies prefer to be rid of negroes,” “they desert the moment danger threatens. As soon as we began our march from Memphis, the negros quit leaving their teams standing in the roads and details of soldiers had to be sent back to bring up the wagons. At Shiloh, all our negro servants fled, and some of them were picked up by boats forty miles down the river. I won’t trust negroes to fight yet, but don’t object to the government taking them from the enemy, and making such use of them as experience may suggest.”[6]

However, some Union soldiers were impressed by the efforts of freedmen soldiers. Chauncey Cooke writes to his mother in July 1863, “I see by the papers there are fifty thousand freedmen under arms and they are doing good service. The poor black devils are fighting for their wives and children, yes and for their lives, while we white cusses are fighting for an idea. I tell the boys right to their face that I am in the war for the freedom of the slave. When they talk about the saving of the Union, I tell them that is Dutch to me. I am for helping the slaves if the Union goes to smash.”[7]

ASSAULTING CONFEDERATE LINES OF VICKSBURG

In his memoirs, General Grant remembers: “The ground about Vicksburg is admirable for defense. On the north it is about two hundred feet above the Mississippi River at the highest point and very much cut up by the washing rains; the ravines were grown up with cane and underbrush, while the sides and tops were covered with a dense forest. Farther south the ground flattens out somewhat and was in cultivation. But here, too, it was cut up by ravines and small streams.”[8]

Federal troops had tried to breach the defensive works, but to no avail. General Grant remembers the final assault: “The attack was ordered to commence on all parts of the line at 10 AM on April 22nd with a furious cannonade from every battery in position. All the corps commanders set their time by mine so that all might open the engagement at the same minute. The attack was gallant, and portions of each of the three corps succeeded in getting up to the very parapets of the enemy and in planting their battle flags upon them; but at no place were we able to enter.” “This last attack only increased our casualties without giving any benefit whatever.” At dark the Union forces were withdrawn.[9]

SIEGE OF VICKSBURG

In his memoirs, General Grant recalls: “I now determined upon a regular siege, to out-camp the enemy, as it were, and to incur no more losses.” “With the navy holding the river, the investment of Vicksburg was complete. As long as we could hold our position, the enemy was limited in supplies of food, men and munitions to what they had on hand.”

The Union trenches were six hundred feet or closer from the Confederate positions, they were so close that both sides could shout out to each other.[10] At one point in the line, General Grant remembers, “the soldiers of the two sides occasionally conversed pleasantly across this barrier; sometimes they exchanged the hard bread of the Union soldiers for the tobacco of the Confederates; at other times the enemy threw over hand-grenades, and often our men, catching them in their hands, returned them.”[11]

The fighting was miserable, HH Penniman of the Illinois volunteers wrote to his wife in early June: “We still lie here waiting for the fall of Vicksburg and expect it will be ours in a few weeks. Grant’s fine army needs a few weeks of rest very much. Marching and countermarching, fighting, watching, and digging, with hot weather, dry and excessively dusty roads and fields, miserable camping places on the ground, and great scarcity of water,” “with short diet, sleepless nights, dirty clothes, absence of tents, distance of wagons, and much confusion among the countless hills, all have aided in rendering the troops debilitated, and most decidedly uncomfortable.”

Our Illinois volunteer continues, “War is a dreadful evil, and the army is a school of bad morals; about nine-tenths of the troops entering the army are irreligious, becoming worse and worse. A great crowd of men, without the restraints of society, and no influence from woman, become very vulgar in language, coarse in their jokes, impious, and almost blasphemous in their profanity.”[12]

The two sides were competing in digging tunnels and blowing up mines under the enemy lines. General Grant remembered “one colored man, who had been underground at work when the explosion took place, who was thrown to our side. He was not much hurt, but was terribly frightened. Someone asked him how high he had gone up. ‘Dun no, massa, but t’ink ‘bout t’ree mile,’ was his reply.” He served the Union cause for the duration of the war.[13]

SURRENDER OF VICKSBURG

By July 1863, it was clear to the Confederates they would not be relieved, and it made no sense to wait to surrender until their provisions had completely run out. On July 3rd, two Confederate officers approached the Union lines under white flags. They proposed an armistice, with three Confederate commissioners meeting with three Union commissioners to negotiate the terms of surrender.

General Grant proposed that instead he meet with Confederate General Pemberton, sending this reply: “The useless effusion of blood you propose stopping by this course can be ended at any time you may choose, by the unconditional surrender of the city and garrison. Men who have shown so much endurance and courage as those now in Vicksburg will always challenge the respect of an adversary, and I can assure you will be treated with all the respect due to prisoners of war. I do not favor the proposition of appointing commissioners to arrange the terms of the capitulation, because I have no terms other than those indicated above.”

Pemberton and Grant had served in the same division in the Mexican War and were old acquaintances. Pemberton did not immediately agree until that evening, as he did not want to formally surrender on July 4th. The terms of surrender were similar to those ending the Civil War at Appomattox Courthouse. The arms of the soldiers would be stacked, but the officers would be permitted to take their sidearms, and cavalry officers could take one horse. The Confederates were fed alongside Union soldiers.

General Grant remembers: “Pemberton’s army was largely composed of men whose homes were in the Southwest; I knew many of them were tired of the war and would get home just as soon as they could. A large number of them had voluntarily come into our lines during the siege, and requested to be sent north where they could get employment until the war was over and they could go to their homes.” The Union Army did not want the burden of caring for this large group of Confederate prisoners.

General Grant continues, “Our soldiers were no sooner inside the lines than the two armies began to fraternize. Our men had full rations from the time the siege commenced to the close. The enemy had been suffering, particularly towards the last. I myself saw our men taking bread from their haversacks and giving it to the enemy they had so recently been engaged in starving out. It was accepted with avidity and with thanks.” The Confederates had only two weeks rations remaining when they surrendered.

How did the Confederate civilians manage during the weeks long Union artillery bombardment? After riding into Vicksburg, General Grant “found that many of the citizens had been living underground. The ridges upon which Vicksburg is built” “are composed of a deep yellow clay of great tenacity. When roads and streets are cut through, perpendicular banks are left and stand as well as if composed of stone.” “Many citizens secured places of safety for their families by carving out rooms in these embankments. A doorway would be cut in a high bank, starting from the level of the road or street, and after running a few feet, a room was carved out of the clay.” “Some of these rooms were carpeted and furnished with considerable elaboration. In these rooms the occupants were fully secure from the shells of the navy, which were dropped into the city night and day without intermission.”[14]

As at the surrender several years later at Appomattox Courthouse, Union soldiers were discouraged from celebrating the end of the long series of battles and the siege at Vicksburg. But individual soldiers were ecstatic in their letters home, as Sergeant Stephen Rollins of Illinois wrote to his mother: “The great work has at last been accomplished, the fight is fought, and the victory won! The great rebel stronghold has at last fallen, and let us thank God fervently.” “Thanks be to God first, who has ruled our affairs to the dismay of our enemies! Thanks next to the patriotism, valor, ability, and energy of Major-General US Grant! Thanks to the soldiers, who have nobly and patriotically performed so many deeds of valor, endured so many hardships, and bravely won so many victories!”[15]

In a succinct letter to General Grant, Abraham Lincoln showed his magnanimous nature in congratulating his victorious general. “I write this now as a grateful acknowledgment for the almost inestimable service you have done the country. When you first reached the vicinity of Vicksburg, I thought you should do, what you finally did: march the troops across the neck, run the batteries with the transports, and thus go below; and I never had any faith, except a general hope that you knew better than I, that the Yazoo Pass expedition, and the life, could succeed.” He recounted one of the engagements, “I thought it was a mistake. I now wish to make the personal acknowledgment that your were right, and I was wrong.”[16]

DISCUSSING THE SOURCES

General Ulysses S Grant wrote his personal memoirs when he was on his deathbed to provide for his widow, this was a best-seller when originally published after 1885, and helps bring alive the many battles of the Civil War, reminding us that history when lived is not inevitable. Due to their nature, the correspondence of General Sherman was less helpful. This collection of the Civil War letters of mostly ordinary soldiers, but also of generals and the occasional letter from President Lincoln, revealed the concerns and thoughts of ordinary soldiers fighting in this epic struggle.

One major source we consulted was the Teaching Company lectures on the Civil War by Professor Gary Gallagher. The battles and maneuvering leading up to the siege of Vicksburg were an elaborate chess game, we encourage you to listen to these lectures to learn about how the quick actions of General Grant ensured the ultimate victory, and how he overruled the misgivings of many of his subordinates in his tactics and strategy, including his associate General Sherman. We also reflected on Professor Gallagher’s reflections on why Union soldiers were willing to fight to preserve the Union, and how the speeches of Daniel Webster inspired many Americans to cherish the Union.

Civil War Through Paintings

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/civil-war-struggle-through-paintings/

https://youtu.be/2hoBOSOBUP8

Why Were Union Soldiers in the Civil War Willing to Fight to Preserve the Union?

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/why-were-union-soldiers-in-the-civil-war-willing-to-fight-to-preserve-the-union/

https://youtu.be/0aak9Mtt0eI

How Did the Speeches of Daniel Webster Inspire the North to Fight To Preserve the Union?

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/how-did-the-speeches-of-daniel-webster-inspire-the-north-to-fight-to-preserve-the-union/

https://youtu.be/etLbkY_zgY0

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Civil_War and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Halleck and Gary Gallagher, The American Civil War (The Great Courses, www.thegreatcourses.com, 2000) and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1862%E2%80%9363_United_States_House_of_Representatives_elections

[2] The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S Grant (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017, 1885), Chapter 30, pp. 292-293.

[3] The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S Grant, Chapter 31, p. 307.

[4] Gary Gallagher, The American Civil War, Lecture 23: Vicksburg, Port Hudson, and Tullahoma, p.93.

[5] The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S Grant, Chapter 30, p. 293-294.

[6] Simpson & Berlin, Sherman’s Civil War, Selected Correspondence of William T Sherman, 1860-1865 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1999), p. 461.

[7] Civil War Letters, From Home, Camp & Battlefield, edited by Bob Blaisdell (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2012), p. 149.

[8] The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S Grant, Chapter 37, p. 370.

[9] The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S Grant, Chapter 36, p. 367.

[10] The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S Grant, Chapter 37, p. 372.

[11] The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S Grant, Chapter 38, p. 380.

[12] Civil War Letters, From Home, Camp & Battlefield, pp. 126-128.

[13] The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S Grant, Chapter 38, p. 380.

[14] The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S Grant, Chapter 38, p. 384-393.

[15] Civil War Letters, From Home, Camp & Battlefield, p. 142.

[16] Civil War Letters, From Home, Camp & Battlefield, p. 146.

5 Trackbacks / Pingbacks