How and why could Confessing Christians either tolerate or support the totalitarian Nazi regime of Hitler? We cannot help but ask that question because we see bulging eyes of the skeletal concentration camp victims looking up in those black and white photographs, but we must realize that nobody in the prewar years could have predicted that the concentration camps would come to define Nazism.

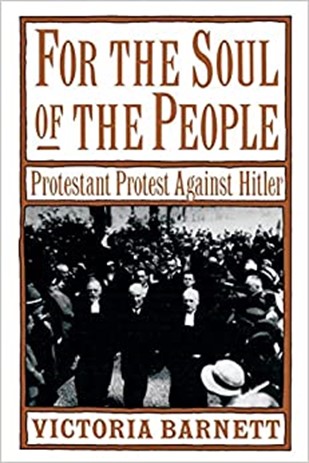

One of the main sources we used for our video on how Christians Kept the Faith in Nazi Germany was Victoria Barnett’s book, For the Soul of the People, she had excerpts from post-war interviews of Confessing Christians in her book. These slides come from this rather long video.

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/christians-under-hitlers-german-nazi-regime/

YouTube: https://youtu.be/QP9UR8fqfvs

This YouTube video: https://wp.me/pachSU-IZ

Germany on the eve of World War II was about 97% Christian, a third were Catholics, two-thirds were Protestants. Therefore, the story of Christianity under Hitler is really two interlocking stories. First, there is the story of the German Catholic Church and its futile attempt to negotiate a Concordat with the Nazis. Once this Concordat was signed the Nazis ignored their obligations under the treaty. Second is the story of the German Protestant Church. The Nazis tried to commandeer the Lutheran and Reformed Churches and turn them into a German Christian Church that denied the Old Testament and the Jewishness of Jesus, glorifying the fatherland and the Nazi doctrines on race. Some churches formed the Confessing Church that resisted Nazi intrusions into Church doctrines. About a sixth of German Protestant Churches were Confessing Churches, another sixth were Nazi German Christian Churches, the rest declined not to be political and to take neither position.

WHY DID MANY CHRISTIANS TOLERATE NAZISM AND ANTI-SEMITISM?

To answer this question, we can listen to post-war interviews of members of the Confessing Church as they struggle to explain the past.

The son of a pastor explained why many Christians went along with the persecution of the Jews under Hitler:

“Just as the average Protestant was middle class and ‘national,’ he was also anti-Semitic. Today you can hardly speak of ‘harmless’ anti-Semitism, but at that time we saw it as harmless.” “I was raised to believe that, until the Jews rejected Jesus, they were a loyal people, a wonderful people. They were farmers and shepherds. Then God rejected them, and since that time they have been merchants, good for nothing, and they infiltrate everything, everywhere they go. And against that you had to defend yourself.” “Certain kinds of restrictions on their civil rights, that was generally talked about and sympathized with.”[1]

One German said this, “This way of thinking was embedded in the Christian tradition (in Germany): the persecutions were hard on the Jews and one had to pity them, but they had brought it upon themselves somehow. Either because there had been Jews who had dominated the business sector or because they had immoral business methods, or, this was a reason the pious, that it was the wrath of God which now, after such a long time, had turned upon the Jews.”[2]

One German explained his experience as a Jewish Christian member of the Confessing Church, and this viewpoint influences many middle-class parish members in our current day:

“As a matter of principle, the German bourgeoisie, to which the overwhelming majority of pastors and parish members belonged, was anti-Semitic in the sense that Jews didn’t ‘belong’ to the church.” “The guilt of the Christians and the church rests in the fact that the commandment to love your neighbor was interpreted or taken to mean that one looked after your Christian brothers and sisters, those who had been baptized. That means that when Christians came into conflict with the state or with the police, the church of parish took care of them as long as it had to do with the church. They didn’t look after these people when it was a political matter. The Christians in the church cared for Christians when something happened because they were Christians. The responsibility for society, the Jews, Social Democrats, communists, gypsies, atheists, the responsibility for all these was not seen as a responsibility of the church.”[3]

The Confessing Church would be persecuted increasingly through the end of the war, and many confessing pastors served time and often died in Gestapo prisons or the concentration camps in Germany. Many Confessing Church students were purposely drafted into military service. Many Confessing Germans wrestled with the question of whether they should have done more during the war to oppose the Nazis, but many who actually did, died in concentration labor camps or on the battlefield.

Though the individual churches initially sought mainly the freedom to worship and congregate without governmental interference, they were increasingly forced to face the many moral challenges thrust upon them.

You never saw an organized resistance in Nazi Germany that you saw in Vichy and Occupied France, but then Germany was the conquerors rather than the conquered. Although Confessing Church was never a resistance organization, some individuals were part of the small German resistance, including the martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

What could the ordinary devout do in such extraordinarily evil times? Should they try to comfort their Jewish neighbors who had been ordered to the train station to be sent to the death camps? Do they help them flee from deep inside Germany? Do they accompany them to the train station? What could they do?

Why didn’t more Germans speak out during the Kristallnacht, when Jewish businesses, homes, and synagogues were attacked, looted, and often burned? One newlywed admitted,

“I frankly admit to you that sometimes you had to push yourself not to be a coward. I had married in 1936.” “I had to weigh every word I spoke on a scale. When you have a child, then you’re not as courageous as the Catholic priests are, with their light baggage.”[4]

One Confessing Christian who was haunted by these choices remembers, “We were never sure whether were doing the right thing or not. We had been brought up differently, and it was war, and then, it’s hard to undertake something against your own country. Later, when young people asked us, particularly abroad, why we hadn’t resisted more, I tried to explain to them how hard it is, particularly during a war, to do something illegal that could lead to punishment,” and possibly imprisonment in a concentration camp.

“We were simply too cowardly. That is what I would say today. That is the great guilt we have taken upon ourselves. It was due to the war. We were against the government, but our men were on the front. My two brothers were also soldiers.”[5] Since they were ‘also’ soldiers, that must mean they were also Confessing Christians.

One confessing German remembers the large number of suicides among the Jews in Berlin, “Jews had to wait one week and a half for a funeral, due to overload caused by twenty to thirty Jewish suicides per day, of which the German people, because of the isolation of the Jews, learn nothing.”[6]

MEMORIES OF CONCENTRATION LABOR CAMPS

Many do not realize that thousands of concentration labor camps were built in Germany and across the Third Reich. One pastor in Germany remembers,

“The concentration camp lay between my two parishes; the borders of the camp were a few hundred meters from my parsonage. From the fields behind my house, you saw the towers and boundary walls of the camp.” “When the prisoners were taken to their workplace, we saw them, emaciated, wraithlike. Parish members and school children often put bread unobtrusively on the street curb, out of pity, so that the prisoners could grab it and get a little more nourishment. This happened even during the war when food was rationed.”

“There were no gas chambers in the Sachsenhausen camp, but they had a crematorium. When the prisoners died as a result of the treatment in the camp, not enough food, overwork, and the gruesome treatment, then they were cremated. We could see the number of murdered prisoners in the perpetually smoking chimneys of the crematorium. Some were murdered when, out of desperation, they ran into the barbed wire.”

“Those of us who lived in the south part of the parish witnessed the Russian POW’s arriving, totally exhausted. They had been transported for weeks, standing and closely penned in cattle cars, and when they pulled up to the train station, they just fell out. This always took place at night, under the glare of spotlights. A tower of corpses rose beside the still living bodies that tumbled out onto the platform. The living prisoners would be driven by the SS men with whips and dogs into the camp. Those who collapsed got a kick that snapped their necks.”

“Our parishes knew what was happening there. The knowledge about the procedures in the camp lay like a poison cloud over our parishes. Because of that, the recognition grew quickly that this war would work its way out on us like the judgement of God.”[7]

There were many labor camps where conditions were harsh, but were not as harsh as the concentration camps. One half-Aryan worker recalls,

“We were housed in military barracks, where twenty-four people slept instead of sixteen. The room was overfilled. But we had an oven in the room, and we had as much wood as we could take from the forest to heat the oven. We received our board, and we even had the chance to steal sugar beets or potatoes from the fields, whatever we wanted, so we had enough to eat.”

Although the camp was under the control of the Gestapo, “we had a camp commandant who screamed like a starling, by the didn’t touch anyone physically. And under the most threadbare pretenses, he gave individuals weekend leaves. I had such a leave once myself.”[8] From the account it seems they were paid very little if anything for their labor, but there was no labor unrest there! They weren’t starved or beaten or overworked, life was good as life could be for a slave in Nazi Germany. Many French POW’s worked in many camps like this camp.

The war brought out the worst in the morally weak. One prison chaplain was discussing his war experiences with a farmer, and he remembered:

“I had SS men in my prison who loaded Jewish children onto a bus and said they were taking them on an outing, and they hanged them in a forest.”

The farmer said, “Oh, oh, what criminals they were.”

The chaplain responded, “They were farm boys from Schlesinger-Holstein. Before, they wouldn’t have bent a hair on a dog or a horse or any animal. But, they hung children.”[9]

The government tried to keep news of these mass murders from the ordinary people. One lady could not recall when she first heard of the mass murders:

“We knew some things, but we never knew the entirety. We knew more than others, but we actually learned the extent of the horrors after 1945. No one ever came back from the concentration camps, and when people did return, they had to sign that they wouldn’t talk, and they were much too afraid to talk.”[10]

The war softened the hearts of many Germans. One German remembers shopping during the time of the brutal Allied bombing of Berlin, the “shopkeeper was talking to another customer whom she knew and said, ‘This is the punishment for what we’ve done to the Jews.’ And she dared to say that much, although I was a stranger in her shop.”[11]

FOR MORE FOOTNOTES, See the main blog of Christians Living in Nazi Germany.

[1] Victoria Barnett, For the Soul of the People, Protestant Protest Against Hitler (New York, Oxford University Press, 1992), p. 15.

[2] Victoria Barnett, For the Soul of the People, p. 125.

[3] Victoria Barnett, For the Soul of the People, p. 133.

[4] Victoria Barnett, For the Soul of the People, p. 140.

[5] Victoria Barnett, For the Soul of the People, p. 147.

[6] Victoria Barnett, For the Soul of the People, p. 137.

[7] Victoria Barnett, For the Soul of the People, p. 102.

[8] Victoria Barnett, For the Soul of the People, p. 177.

[9] Victoria Barnett, For the Soul of the People, p. 180.

[10] Victoria Barnett, For the Soul of the People, p. 148.

[11] Victoria Barnett, For the Soul of the People, p. 170.

Be the first to comment