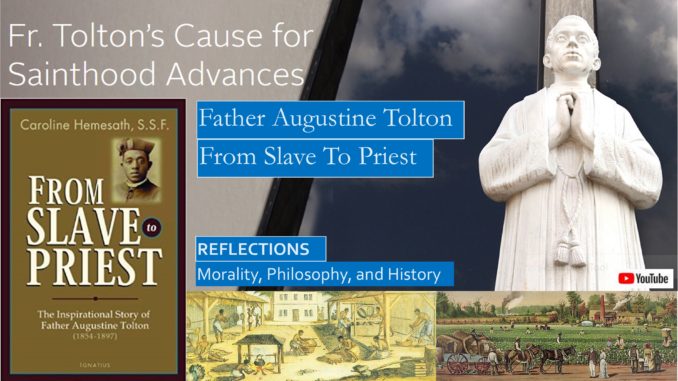

What is most remarkable about the biography of Father Augustine Tolton, “From Slave to Priest,” is how many Catholic clergy, including priests, nuns, and bishops, both American and Roman, both in those years after the Civil War and during Reconstruction, were eager to help this barely literate former black slave gain a clerical education and encourage and enable him to study for the priesthood.

What is also remarkable is how many of these missionary priests from Germany and Ireland were willing, in homily after homily, month after month, year after year, to persistently and without much success to encourage their white parishioners to treat their fellow black freedmen with the dignity and respect that is due to all of God’s children. His biography, which is really a hagiography of a prospective saint, was written by Sister Caroline Hemesath in 1973. She had learned of his remarkable ministry as a priest in Chicago in 1933, and she interviewed many who knew Father Tolton when he was alive.

Please view the YouTube video: https://youtu.be/dZbzWJkAf5k

What is also remarkable is how many of these Catholic clergy, after Father Tolton attended seminary and was admitted into the priesthood in Rome, encouraged him in his ministry to his black parishioners, and how they came to respect him and even admire his life of faith and dedication, so much so that he is now being considered for canonization.

This biography would have been impossible if the many people Father Tolton had corresponded with over the years had not kept their caches of letters, we presume that Father Tolton must have been punctilious in keeping the responses to this correspondence. The fact that these church officials and friends would have kept the correspondence with an ex-slave is also remarkable.[1]

Father Tolton left for us a living example of persistence, patience, unending forgiveness, and lovingkindness that he showed in the years and years it took for him to gain an education and work in the church in addition to working in a factory to support his mother and siblings. Not only did Father Tolton lean how to read and write in English, Latin, and biblical Greek, but since many Catholic parishes in his area were German, he was also fluent in German.

The process for the beautification and eventual granting of sainthood to Father Augustine Tolton began in 2010. In June 2019, the Archdiocese of Chicago says that “Pope Francis has issued the declaration that Father Augustus Tolton lived a life of heroic virtue thus advancing him to the title, The Venerable Father Augustus Tolton.”[2]

BORN INTO SLAVERY

Most slave autobiographies begin with noting how slaves were viewed as little more than talking livestock, with no feelings of their own. The biographer tells us that the Catholic families in the border state of Kentucky that owned the Tolton family members respected, somewhat, though not completely, the human dignity of their slave families. Not only were their slaves well-fed with decent clothes, the Catholic owners were concerned about the state of the souls of their slaves. They ensured that their slaves received religious instruction and permitted them to partake of the Catholic Sacraments. That included the sacrament of marriage, the owners permitted the slave parents of Augustine Tolton to be formally married by a Catholic Priest in the Catholic Church. The Tolton family was permitted to live together in one house although the parents were owned by different masters. Amazingly, the slave children were recorded in the parish registry when they were born, including his mother, Martha Jane. Unlike many slaves in the Deep South, Tolton was not the last name of their master, but was a real last name. The biographer does not mention it, but we can presume that husbands and wives were not sold separately, which often happened in the Deep South.

But they were still slaves, and they were still treated like slaves, and their masters saw nothing wrong with treating them as slaves. Literate slaves were seen as dangerous slaves, quick to run away, so slaves were never taught how to read and write. Like all slaves, they could be whipped and beaten by their masters and overseers at will for any reason, or no reason, and both the parents and their children were brutally whipped, with lashes, many times by the overseer trying to whip more work out of them. Dawn to dusk, every day, except maybe Sunday, they toiled in the fields.

The biographer notes, “Under slavery there was great estrangement, a total lack of communication, a latent hostility which would, and at times did, break through the varnished surface, with violence and murder. Slavery rested upon the ability to use unmeasured force, and every slave and master knew it.”

On at least one occasion, one or more slave families were broken up. The biographer tells us that when Augustine Tolton’s mother was a child the owner’s daughter was married. On the day of the wedding the owner went through his slave quarters and brushed paint on the forearms of some of his slaves, including the young slave girl who was Augustine’s future mother, seemingly at random. The slaves were terrified, what would become to the slaves who were painted?

Sometime later the slaves with paint were locked in the meeting hall, including Martha Jane. During the wedding festivities the father of the bride brought the radiant couple to the meeting hall, unlocked the door, and exclaimed to the newlyweds, Behold, your dowry!

After the cart carrying the slaves of the newlywed was hitched, Martha Jane’s younger brother Charley ran over and bear hugged his precious sister, as if somehow he could prevent her from being taken away. The overseer brutally whipped him until he let go.[3]

CIVIL WAR AND FREEDOM

In the beginning of the war, Kentucky was not far from the Union lines. Encouraged by his wife, Augustine Tolton’s father joined the thousands of slaves who fled to the Union army lines where he wanted to sign up as a soldier, promising to send for his family when they were free. They never heard from him again. After the war they found his name on a Union Army casualty list. His last testament was that his children “must not be slaves; they must learn to read and write; they must have a better life than we had.”

Conditions worsened as the war progressed. The remaining slaves had to work ever harder to make up for the slaves who ran away. Martha Jane feared for the safety of her children, slave traders were prowling for slave children to kidnap. The lashings increased. Civil order was disintegrating.

One night Martha Jane with her toddler and two young children with a little bit of food made their way to the Mississippi River. Freedom was many days journey away. During the day they mingled with friendly neighborhood plantation slaves. Confederate officials actually caught them, but by chance some Union soldiers encountered them, kept the handcuffs off them, claiming jurisdiction, and letting the family go.

Finally, they were in a dilapidated rowboat, with Martha Jane rowing to freedom to the free states of Illinois. The biographer writes, “In later years Augustine Tolton often recalled the passage across the wide Mississippi. His mother, wholly inexperienced at rowing, struggled frantically with the oars and caused the small craft to veer crazily from side to side.” Then they “heard the angry voices of Confederate men shouting threats and curses. One of them raised his musket, firing repeatedly. Undaunted by the whistling bullets, Martha Jane ordered her children to lie flat in the bottom of the boat. The baby screamed from sheer bewilderment and fright. The boys did what they could to calm her, although they also cried all the way. Relying entirely on the protection of divine power, the determined mother clung to the oars and succeeded in placing a safe distance between the boat and the chagrined slave hunters.”

“Although Martha Jane had been without food for days, she had the strength to bring her children to safety.” “Kneeling upon the ground, the valiant woman gathered the weeping children into her arms. Tears streamed down her dark cheeks as she said, ‘Now you are free. Never, never forget the goodness of the Lord.’”[4]

LIFE IN QUINCY, ILLINOIS

They were found by a mixed black and white work crew at an Illinois wharf, feeding them from their lunch boxes. When they gave the mother directions to Quincy, twenty miles down the road, “for the first time in her life Martha Jane heard herself called Mrs. Tolton, and despite her weariness that gave her new courage and a sense of dignity.” They had to travel quietly, Confederate spies were known to kidnap any blacks they could find to sell into slavery.

Quincy, a river town with a population of 25,000, including 300 blacks, with many schools, churches, and factories, was known as a haven for fugitive slaves. Mrs. Davis, a widow with a young daughter, offered to share her shack with them for the next few years. One mother worked nights, the other days, so they looked after each other’s children.

During their time at Quincy, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, and then after a few years the Civil War ended after the surrender of Robert E Lee at Appomattox Courthouse. Both mother and her sons worked as stemmers in the tobacco factory for ten hours a day, six days a week, which was a great improvement over working in the fields under the overseer’s whip.

Many of the black Catholics attended St Boniface Church, where Father Schaffermeyer preached the Gospel and sermon in both German and English. Augustine was the first black to attend the Catholic School, and he learned to read and write in both languages. The white boys were particularly cruel with their racial slurs.

His mother switched to St Peter’s Church, where the German priest Father McGirr befriended the blacks, and where Augustine had fewer problems. Many of the white parishioners threatened to leave the church if they were too friendly with the blacks, but Father McGirr pushed back, preaching sermons on how Jesus came to save all Christians of all colors.

Father McGirr took a special interest in Augustine, and one day asked him if he thought about becoming a priest, and if that came to pass, Augustine would be the first black priest in America, though the Church had many black priests in Africa. But there was no enthusiasm in the hierarchy for a black priest. Since it would be impossible for Augustine to be admitted to college, let alone pay the tuition, he decided to give him lessons in Greek, Latin, and theology, which meant that in a few years he could read and write four languages, while he was working both at the tobacco factory and as a church janitor. After a few years he started studying under Father Richardt at St Francis College, which at this time was really a preparatory school.[5]

Year after year Augustine studied his Aquinas and Latin and Greek. Year after year his German priest wrote letters trying to get him admitted to a seminary, always with the response that people were just not ready for a black priest. Year after year they had to counter hostility towards their black parishioners. As our biographer tells us, “this dwindling black attendance saddened the priests; they expended every effort to prevent further loss of membership.” They preached the Gospel messages of “fraternal love: ‘As long as you did it to the least of my brethren, you did it to me; he who says he loves God and hates his neighbor is a liar;” and if your brother feels you wronged him, “leave thy gift at the altar and first be reconciled to your brother.’ Despite the pastoral exhortations, both parishes suffered an almost complete alienation of black members.”

The priests tried again, they started an apostolate for blacks, starting with a black St Francis Parish School. Augustine taught some of the classes, and he and his mother recruited many ghetto black children for the school. Also, our biographer tells us that “Augustine frequented the city’s saloons, where whites and blacks intermingled in daily and nightly bouts and brawls. He listened patiently, often far into the night, to a tangled woe drawled out by a bleary-eyed drunk.” Although many of his “converts” were temporary, he tried to convince many of these drunks to attend the Temperance Society meetings. “The silent, inobtrusive activity of Augustine Tolton was largely responsible for the success of the apostolate to the blacks of Quincy. Both he and his mother were tireless in their efforts to reinstate members of their race in the Church and to encourage others to study the Catholic religion.”[6]

THROUGH THE DARKNESS TO THE LIGHT

Finally, some encouragement. Our biographer tells us, “The year 1879 was a crucial year for Augustine Tolton. He was twenty-five years old. The regular tutoring by dedicated priests and nuns, his habitual self-discipline, his faithful observance of religious duties, and his twelve years of honest service as a wage earner had formed a character distinguished by determination, integrity, and leadership.”

The priests kept writing letters trying to get him admitted to an American seminary. Father McGirr told him why the Franciscan seminary was so reluctant to admit him, though he was eminently qualified. “These (foreign) priests were not accustomed to the American attitude towards the blacks. They deplored the fearful race hatreds and antagonism. Whites threatened them with fines and even violence when, in some areas, they befriended Negroes. This, as well as the many legal restrictions which controlled racial relations, are among the reasons why their superiors refuse black applicants,” “and the period of Reconstruction in the South has intensified popular resentment against blacks. Some Franciscans think that their work in the cause of Christ would be hindered, that their membership would decrease, and their influence diminish if blacks were seen in their ranks.”[7]

OFF TO ROME, AS A SEMINARIAN

The priests asked Augustine if he would like to be a missionary priest in Africa, and he responded that he would go anywhere the church asked him to go. His priests wrote lengthy, glowing records of recommendation, with the results of his education, and wrote to the head of the Franciscan Order in Rome. Finally, Augustine was accepted to attend the pontifical college in Rome in 1880, so he could train to be a missionary priest. A crowd of people bade him well at the train station, “family and friends, old and young, black and white, priests, college students, and school children.”[8]

In Rome, Augustine felt welcome. Our biographer tells us, “in a flood of relief and new happiness, Augustine discovered that the seventy or more fellow seminarians represented many races and nationalities, all of whom accepted him unconditionally and sincerely.” “The discrimination and prejudice that he had so often suffered in America all his life were unknown in the pontifical college.” “He experienced the security of equality and justice, a sense of dignity and worth, the comfort and companionship of friends, the joy of mutual charity and benevolence. He profited by the ready helpfulness of classmates with whom he could study and discuss, give, accept, and share. He never felt lonely, unwanted, or out of place. He was treated as a person, as a member of the Church, as a child of God.”[9]

For six blissful years Augustine studied in Rome before he was ordained to be a priest, with the special red sash of the pontifical college of Rome. His ministry would not have been filled with frustration if he had been sent to Africa as a missionary priest, but the Cardinal told him, “America needs black priests. America has been called the most enlightened nation. We will see whether it deserves that honor. If the America has never seen a black priest, it must see one now.”

“Augustine bowed his head and covered his face with his hands. “Back to America? Back to the country where I was a slave, an outcast, a hated black? Must I go back to America, where I was not wanted as a priest? Where seminaries and religious orders were not ready for someone like me? Lord, I can conquer ignorance, weakness, and heathenism. But Lord, I can conquer ignorance, weakness, and heathenism. But Lord, I cannot conquer the racial hatred in America.”[10]

PRIESTHOOD AND FRUSTRATION IN QUINCY

In July 1886, Father Augustine Tolton was installed as the first black priest in America serving the negro St Joseph’s parish in Quincy, which also had a school attached. In the first few years he had a measure of success, membership increased somewhat, and he had both black and white parishioners. Since the blacks were either poor or downright destitute, they really could not support the parish, the financial support of the white Catholics was critical for the success of St Josephs. Our biographer tells us, “Father Tolton won the hearts of old and young alike. The secret of his success lay in his innate simplicity and genuine love for all with whom he came into contact. He never tired of telling his people that God cared for each one of them and that he had a deep concern for the welfare of every one of his children.”[11]

But the white priest of St Boniface parish was facing a mountain of debt, and he was jealous of the white support Father Tolton was able to attract. After several years of obstruction, he forbade the white Catholics from supporting or even attending the black parish of Father Tolton, proclaiming that he was their only to minister to the black Catholics. Other pressures from Protestants and the unending misery of living in poverty also contributed to a drastic drop in membership by the black parishioners as well. The death knell came when the bishop ordered him to refrain from ministering to whites.[12]

ST MONICA’S CHURCH, FIRST BLACK PARISH IN CHICAGO

Father Tolton was granted permission to minister to the first black Catholic parish in Chicago, St Monica’s Church. The church was started in a storefront in the ghetto of Chicago. Construction began on a permanent church, and although it was finished to the point where services could be held, construction was not completed in his lifetime. Archbishop Feehan of Chicago permitted Father Tolton to solicit funds to support St Monica’s, as his black parishioners were employed mostly as servants and were mostly destitute. His mother was able to move to Chicago to assist him, but he started having health problems and did not have the energy he had in his youth.[13]

Our biographer tells us, “In spite of his fatigue, Father Tolton made the daily rounds of his parish, stepping over the uneven brick pavements and cobbled sidewalks or climbing steep rickety stairs. All too often he was horrified by the squalor, the ravages of poverty and disease, the prevalence of dissipation and vice. Many of his people were ex-slaves and totally illiterate; others suffered just as severely from moral deprivation.”

“Day after day Father Tolton was seen coming in or out of the shacks, the rat-infested hovels and tenement houses. He listened compassionately to complaints of unemployment, desertion, injustice, depravity. Father Tolton knew how to bring hope and comfort to the sick and dying; he knew how to mitigate human suffering and sorrow because eh himself had experienced the lash of the slave driver as well as the lash of the white man’s tongue.”[14]

In July 1897, when walking home from the train station as the temperature hit 105 degrees, Father Tolton fainted, and soon died. Thousands paid their respect at the funeral of this beloved priest who worked alone for so many years. He was only forty-three years old.[15]

[1] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1973, 2006), pp. 17-18.

[2] https://tolton.archchicago.org/ , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustus_Tolton

[3] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest, pp. 19-28.

[4] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest, pp. 29-34.

[5] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest, pp. 35-94.

[6] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest, pp. 95-101.

[7] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest, pp. 113, 116.

[8] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest, pp. 123-124.

[9] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest, pp. 134-135.

[10] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest, p. 154.

[11] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest, pp. 179-180.

[12] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest, pp. 182-187.

[13] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest, pp. 200-211.

[14] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest, p. 212.

[15] Caroline Hemesath, From Slave to Priest, pp. 217-220.

2 Trackbacks / Pingbacks