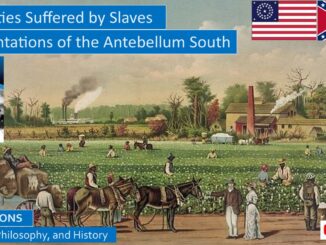

Booker T Washington’s autobiography, Up From Slavery, offers an interesting glimpse in what it was like to be born a slave, live through the tumultuous Civil War era, and as a young man to experience the consequences blacks faced with the end of Reconstruction when the Ku Klux Klan night-riders enslaved the former black slaves anew through terror by lynching them, burning their bodies and their farm and their churches, suppressing them and denying them justice, even denying them the ability to defend themselves in daylight through the courts.

Please view our video, is has material not included in this blog: https://youtu.be/yxDnJ6sBoJc

Frederick Douglas, born to the prior generation of black leaders, was also a former black slave and abolitionist who was a freedman and was able to publicly agitate for the equal treatment of blacks, including black suffrage, allowing blacks the right to vote. Likewise, WEB Dubois, co-founder of the NAACP, born in the subsequent generation of black leaders when tensions had eased slightly, was likewise able to break with Booker T Washington to publicly agitate for the equal treatment of blacks. But Booker T Washington was the leading black leader during the height of the KKK’s power, where anyone who publicly called for black suffrage, or even hinted that blacks were even capable of participating in governing or even holding any position of authority over white men, was risking the judgement of the noose and the lynching tree, a judgement that could not be appealed to the courts or even prevented by law enforcement, since many sheriffs themselves rode at night under the white hoods of the KKK night-riders. Booker T Washington does mention black suffrage a few times in his autobiography, but he is more accepting of the inequalities blacks had to suffer in his times.

We must withhold any judgement of Booker T Washington when he tactfully is forced to concede that it was misfortunate that blacks were prematurely granted the right to vote and hold office, especially when many black officeholders during the Reconstruction period were illiterate. We must withhold any judgement when he encourages blacks to win over their white taskmasters by being industrious workers, not workers who threaten white livelihoods, but rather docile hard-working field and factory workers, seeking to be tradesmen, or teachers training the next generation of black workers. We must withhold judgement when he refuses to directly condemn violent white supremacy, but rather simply urges whites to welcome and employ docile and industrious black agricultural and trade workers.

We must remember how Booker T Washington as a leading educator founded the Tuskegee Institute and schools across the South that taught eager blacks the practical job skills they needed to raise themselves out of abject poverty into moderate prosperity. We must remember that how his politically correct conciliatory rhetoric enabled him to raise vast sums of donations from white business philanthropists, including Andrew Carnegie and John D Rockefeller, to fund the building of dozens of black schools.[1] We also must remember that he secretly helped fund the activities of his rival, WEB Dubois and the NAACP, which suggests that he recognized that the next generation of black leaders could be far less subservient. We must remember that all black leaders lived figuratively with a loose noose around their neck that could be strung over a tree limb and pulled tight any night, we must remember that Booker T Washington was only partially protected from this fate by his national prominence and fame.

Booker T Washington briefly mentions in his autobiography describing the horrors of the Ku Klux Klan night-riders who lynched and terrorized the blacks in the Deep South without any fear of retribution or justice. In one section he suggests that this terror sprouted full bloom then quickly withered during Reconstruction.[2] His criticism of the KKK is unsparing but not sensationalist, he knew as well as we know that lynching was the scourge of the Deep South for many decades, but he does not want to dwell on this narrative, the story he wants to tell both his white and black audiences is that the Negro, with proper education, when given a chance can be as good or even a better employee or business owner than any white man.

CHILDHOOD AND PROPER NAMES

Booker comments that when his master purchased his mother at a slave auction, her purchase attracted as much attention as a new horse or a new cow. He never knew his father, did not even know his name, he supposed that his father was a white man living in a near-by plantation. Was this rape? He does not go there. He does mention that slaves are only known their first names, sometimes with the last name of their masters appended to theirs.

Booker never tells us his master’s last name, hinting that he never wanted to be known by his master’s last name, and indeed we never learn his master’s first name. As far as Booker was concerned, he did not have a last name until he went to school. He only tells us the first name of the master’s son, Mars’ Billy, diminutive for master, from fond memories of how slaves nursed him as a baby, how he was their playmate, and how he pleaded for mercy when the overseer was whipping the slaves. We surmise this was a modest and marginal plantation with at most a few dozen slaves. Booker says his master was not especially cruel, which meant he was not especially kind either.

Since his mother was the plantation’s cook, the family’s one room small cabin was also the plantation’s kitchen, with a hearth rather than a proper stove, windowless, with a door with uncertain hinges that let in the Virginia cold during the winter. There was no kitchen table, nor any proper furniture of any kind. There were no family meals, they ate their sweet potatoes and corn bread and pork on the run. Exhaustion ended the day, everyone slept among piles of rags on the dirt floor. The children only had one shirt, always an inexpensive flax shirt. You had to break in new flax shirts, wearing a new flax shirt was like wearing a shirt with hundreds of small needles.

Unending toil, dawn to dusk, was their life. Not only did Booker has no memories of sports or play as a youth, when he was young the thought that a youngster would have time to play never came to mind. When he was old enough to walk he was put to work tending chores, cleaning the yards, carrying water to the men in the fields, taking corn to the mill to be ground. Born in 1858, Booker was still a little boy when the Civil War ended, which meant he was not old enough to work the fields of the plantation.

Booker had vivid childhood memories of the Civil War. The front lines never reached their plantation, he remembers how the slaves learned about the Emancipation Proclamation freeing all the slaves in the rebelling Southern states and other war news by eavesdropping conversations in the post office. He remembers his mother kneeling over her children at night, fervently praying that Lincoln and his armies would win the war, and that one day she and her children would be set free. He remembers when the sons were all sent to war for the Confederacy, how the slaves were honored when it was their turn to sleep in the big house so the ladies of the plantation would not be alone, how their slaves we eager to protect them from possible deserters and intruders. He remembers fondly how the slaves were eager to nurse Mars’ Billy back to health as best they could when he returned wounded as a wartime casually.

THE END OF THE CIVIL WAR, THE BEGINNING OF FREEDOM

Booker remembers the excitement felt by the slaves after the war when they learned there would be a big meeting at the big house in the morning. Booker remembers that morning: a Union officer “made a little speech and the read a rather long paper, the Emancipation Proclamation, I think. After the reading we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased. My mother, who was standing by my side, leaned over and kissed her children, while tears of joy ran down her cheeks. She explained to us what it all meant, that this was the day for which she had been so long praying, but fearing that she would never live to see.”

Booker continues, “For some minutes there was great rejoicing, and thanksgiving, and wild scenes of ecstasy. But there was no feeling of bitterness. In fact, there was pity among the slaves for our former masters.” Why would they pity their masters? “Deep in their hearts there was a strange and peculiar attachment to “old Master” and “old Missus,” and to their children, who they found it hard to think of breaking off. With these they had spent in some cases nearly half a century, and it was no light thing to think of parting.” Plus, slavery had crippled the souls of both the masters and slaves. The white masters were so used to the slaves doing everything for them that they had no marketable skills, and the women did not even know how to cook or keep the house While the white masters never had to work hard, the black slaves never tried to work hard either since there was no real incentive to work hard, which meant that the plantation was never properly maintained, fences and doors were in disrepair, everything needed painting, nothing worked like it should.

One by one the older slaves wandered back to the big house to discuss with their “old Mars” how they could stay on as freed workers. His mother felt no attachment at all to her former master. [3] Booker did not know he had a stepdad, he lived on a neighboring plantation, but soon after the war he moved to coal mining country West Virginia and sent for the family to join him.

Booker never shares with us the name of his stepdad, we can surmise from his autobiography that his stepdad, like his old master, was not especially cruel, not especially kind. They lived in a one room cabin that was even worse than the cabin at the plantation. Unlike the plantation, many black and white low-lifes lived in some of the cabins, often there were drinking and carousing with late night fights many nights. But here they were free.

Unending toil, dawn to dusk, was their life. First his stepfather found him a job working a salt-furnace, often starting his workday at four in the morning. After some time he got work in a coal mine. Booker tells us, “the work was not only hard, it was dangerous. There was always the danger of being blown to pieces by a premature explosion of powder, or of being crushed by falling slate. Accidents were frequent, we were in constant fear.” Many small children worked in the coal mines, with no hope of gaining an education. “Young boys who begin life in a coal-mine are often physically and mentally dwarfed. They soon lose ambition to do anything else than to continue as a coal-miner.”

BOOKER T WASHINGTON STARTS HIS EDUCATION

Like many former slaves of all ages, Booker had a great thirst for education. Booker, on his own stubborn initiative, started his education in West Virginia. Sometimes his stepfather allowed him to attend day classes, which was like heaven to young Booker, but mostly his education was at night classes after a full day of back breaking work. Their family never had enough money and food and clothes to get by, so his stepfather tried to keep Booker working all the time, while his mother encouraged as best as she could for Booker to get an education. We encourage you to read his autobiography for details in his strivings to become educated.

Booker claimed his last name when he attended his first day of class. He was conscious of how many of his more well-off classmates had better clothes and hats than he had. They were recording attendance and everyone before him gave their first and last name. When his turn came, he thought about it, and decided his last name was Washington. When he got home he told his mother about his new last name. His mother informed him she had given him the last name of Taliaferro, which was news to him. So now he was now known as Booker T Washington.[4]

Booker T Washington was hard working, but he decided that any job would be better than digging out coal in perpetual darkness and danger underground. He had to get out of there. He heard there was a vacancy in the household staff of General Lewis Ruffner, owner of the salt-furnace and coal mine. Booker would be working for his wife, Mrs. Viola Ruffner from Vermont. The pay was a meager five dollars a month. She could not keep servants, she was much too strict, most servants stayed three weeks at the most. But Booker came to respect Mrs. Ruffner, in time counting her as one of his best friends, he worked for her for a year and a half.

General Lewis Ruffner and Mrs. Viola Ruffner are the first whites in Booker T Washington’s autobiography whom we know by their full proper names. Booker may be humble, but if you are a white who did not treat Booker with respect, you do not earn the right to be called by your proper name in his autobiography. Mrs. Ruffner treated him with dignity and respect as she would treat any white employee, and he learned from her the dignity of work. Booker T Washington remembers, “she wanted everything kept clean about her, she wanted things done promptly and systematically, and above all she wanted absolute honesty and frankness. Nothing can be slovenly or slipshod; every door, every fence, must be kept in repair.” Mrs. Ruffner encouraged him to continue his education, allowing him time off to attend classes an hour a day.

Booker T Washington sought to be admitted to Howard University, a leading black college five hundred miles away. He worked and scraped and saved and few neighbors gave him a few dollars, and he took trains and stagecoaches to Richmond where his money ran out. He went into the hotel to try to find a meager place to stay out of cold, but the desk clerk immediately told him they would not provide blacks food or lodging under any circumstances. For the next few days he worked at an odd job loading a ship in port to pay for meals, sleeping under the sidewalk to save enough to travel the remaining eighty miles to Hampton.

Out of the blue Booker T Washington showed up on the doorstep of Hampton Institute. There was no room at any inn nearby for him to freshen up, he had about run out of money, he presented himself to the head teacher poor and dirty and smelly from the long journey under the hot Virginia sun. She initially said there was no room for him, but he stayed waiting for several hours. Finally, she gave him a broom and said the recitation room needed sweeping.

Booker T Washington pretended he was still working for Mrs. Ruffner. He not only swept the room three times, he dusted and wiped down the walls and each table, chair, and desk four times and the closets also. When this Yankee head teacher wiped her glove vainly looking for any dust at all anywhere in the room or the closets, she quietly remarked, “I guess you will do to enter this institution.”

Booker T Washington fondly remembers, “I was one of the happiest souls on earth. The sweeping of that room was my college examination, and never did any youth pass an examination for entrance into Harvard and Yale that gave him more genuine satisfaction.”

In his autobiography we learn the proper name of this teacher after she offers him the position of janitor, in time she became quite impressed with the industriousness of our Booker T Washington, he tells us her name was Miss Mary Mackie. In time the headmaster of the school, the former Union General Samuel Armstrong, was also quite impressed with our friend. Before Booker T Washington worked during the day and went to school at night, now he went to school at night and worked during the day.

Booker T Washington remembers of his new experiences: “The matter of eating meals at regular hours, of eating on a tablecloth, the use of the bathtub and the toothbrush, as well as the use of sheets upon the bed, these were all new to me.” And he had decent clothes picked from barrels of used clothing shipped by northern patrons.[5]

We encourage you to read his autobiography to learn more about his years attending Hampton Institute. After Booker T Washington graduated, he was elected to teach at the colored school at his former home in Malden.[6] After several years he was invited back to teach the newly admitted Indian students at Hampton. He remarked that these Indian students, despite their negative reputation, “were about like any other human beings; that they responded to kind treatment and resented ill-treatment.”

Booker T Washington tells us a story about Frederick Douglass, the black abolitionist. He was once forced, because of his color, to ride in the baggage-car of the train. When some of the white passengers commented on how he should not have been degraded in this manner, he replied, “They cannot degrade Frederick Douglass. The soul within me no man can degrade. I am not the one who is being degraded on account of his treatment, but who are inflicting it upon me are those who degrade themselves.”

Booker T Washington also tells a story about his namesake, George Washington, who once tipped his hat in response to a colored man who tipped his hat to him on the road. His white friends criticized him for this courtesy, but George Washington asked, “Do you suppose that I am going to permit a poor, ignorant, colored man to be more polite than I am?”[7]

BLACK EDUCATION AFTER THE CIVIL WAR

Booker T Washington found that many blacks had unrealistic expectations about the benefits of education. Many blacks were raised on rural plantations like he was, many of these blacks were treated literally like they were talking livestock and had no concept of hygiene or table manners. This guaranteed their embarrassment if they associated with whites in any way. He tells us, “we wanted to teach the students how to bathe; how to care for their teeth and clothing. We wanted to teach them what to eat, and how to eat it properly, and how to care for their rooms. Aside from this, we wanted to give them such a practical knowledge of some one industry, together with the spirit of industry, thrift, and economy, that they would know how to make a living after they left us.”[8]

It was only natural that these students would want a professional job when graduating from a college so they would no longer have to work under the hot Southern sun, and many of them were able to get low-paying teaching jobs, but other than teaching there were not many professional jobs available for blacks. Many Hampton graduates instead became Pullman-car porters and hotel waiters.[9]

Eighty percent of the jobs in the South were agricultural jobs, and agriculture and the building trades were where the best paying jobs were for educated blacks. From its inception, Tuskegee was primarily a technical college, teaching its students practical job skills that would enable them to get hired for decent jobs in the Southern economy, and educated teachers who could teach these subjects. It was not uncommon for a Tuskegee graduate to double or triple the productivity of a farm using the latest farming techniques.

Booker T Washington was also concerned that many black preachers really were not qualified to preach, and many were illiterate. He tells the story of a “colored man in Alabama, who, one hot day in July, while he was at work in a cotton-field, suddenly stopped, and, looking towards the skies, said, ‘O Lawd, de cotton am so grassy, de work am so hard, and the sun am so hot dat I b’lieve dis darky am called to preach!’ ”[10] Although Tuskegee was a secular school, eventually it included Bible Study classes as part of the curriculum so black preachers would be better qualified.

BOOKER T WASHINGTON AT TUSKEGEE INSTITUTE

The Alabama legislature had appropriated two thousand dollars to start a school in Tuskegee. General Armstrong was asked to recommend if he knew any qualified white men who could organize and take charge of this new colored teaching school. General Armstrong replied that he did not know of any qualified white men, but that he knew a highly qualified educated black man, recommending Booker T Washington.

Tuskegee was a small town of about two thousand that was more progressive than most since it had a small white school. This was in the black belt, so named because of the thick, dark and naturally rich soil that made this prime agricultural land, attracting large plantations with a large work force.

When he traveled to Tuskegee, he discovered that there were no buildings for the school, and the appropriation only covered teacher salaries. The first classes were held in a renovated repurposed stable and hen-house. Booker T Washington introduced himself to both black and white town leaders seeking assistance in building the new school. Soon an abandoned plantation whose big house had burned down came up for sale, and Booker T Washington was able to collect enough donations locally to purchase this for the school.

He made the strategic decision that the students would do all the work building the campus themselves, which would gain them valuable trade experience, whether they wanted to become tradesmen themselves or teach at a trade school. Booker T Washington initially encountered resistance from the first group of students, they felt they no longer had to do manual labor while they were in college, but when they saw the master of the school roll up his sleeves and get to work, they worked beside him.

The students took great pride in their school since they helped build it. The students also planted crops in the fields of the former plantation. Mistakes were made, and they learned from their mistakes. They wanted to make their own bricks, especially since there was no brickyard nearby. They learned bricks were tricky to manufacture, they ruined three kilns before they succeeded with their fourth kiln. The school then sold bricks and farm produce and other products to the surrounding white businesses, which gained credibility for the school and better enabled its graduates to find decent paying jobs.[11] We invite the reader to read his autobiography himself to learn about this fascinating history.

Over the years they built more and more buildings on campus, and more and more black students enrolled in their classes, many of them just ad dirt poor and ignorant as was Booker T Washington when he first showed up at Hampton not too long before. The financial needs of this growing college soon outstripped the capacity of the local community to finance the expansion. He asked for assistance, and General Armstrong helped him his first fund raising lecture tour and fund-raising trip up North, with Hampton footing the expenses for the trip.

Booker T Washington was an excellent administrator and delegator, he not only believed that the staff should help build the school, they should learn how to run the school also. When Tuskegee really started expanding he would spend six months out of the year crisscrossing Northern cities, giving lectures and visiting philanthropists looking for additional funding for his projects. He knew had to dwell on the positive, praising the many whites who supported black education, but not dwelling on the negative, including the many lynchings and humiliations and discriminations that dogged him and every black man of his era, so he could make a good impression of the moneyed white Northern philanthropists and businessmen.

Booker T Washington was always persistent and patient, and his persistence and patience paid off during the many years he spent fund-raising. Usually, the really large donations came from businessmen he had been calling on for many years. The businessman who donated five dollars this year might donate five thousand a few years from now, and fifty thousand in his will. Carnegie eventually donated twenty thousand for a library. The Alabama Legislature increased their annual appropriation, and several trust funds also donated substantial sums annually.[12]

SPEECH AT THE ATLANTA EXPOSITION

Booker T Washington was perhaps the first black to run a major institution, his Tuskegee Institute, in the Deep South. He is most famous for his speech at the Atlanta Exposition in 1895, which he also helped to organize and promoted during his many fund-raising trips through the North. This was the very first time a black man addressed such a large and influential body of white businessmen and white national politicians. All the major newspapers in the country promoted the Atlanta Exposition, which included a large Negro exhibit which sought to encourage businessmen to hire and work with the many blacks who sought greater economic opportunity.

The speech was a resounding success. When the speech ended, Governor Bullock of Georgia and many others rushed across the platform to congratulate him. The newspapers enthusiastically reprinted the speech from coast to coast. He later received a letter from President Cleveland congratulating him for his speech.

We must remember this speech was the proper speech for him to make in 1895, at the height of Jim Crow, the KKK terrorism and lynchings, when blacks were effectively barred from seeking justice from the police and the courts. We must remember this speech was a sales pitch, pure and simple, to convince white businesses to hire more black workers, and do business with more small black businesses and contractors.

We encourage you to read the entire speech (see footnotes), Booker T Washington begins:

“One third of the population of the South is of the Negro race. No enterprise seeking the material, civil, or moral welfare of this section can disregard this element of our population and reach the highest success.”

This section was addressed to the black workers, and to the white man, assuring him that the black worker would work hard for his business:

“A ship lost at sea for many days suddenly sighted a friendly vessel. From the mast of the unfortunate vessel was seen a signal: “Water, water; we die of thirst!” The answer from the friendly vessel at once came back: “Cast down your bucket where you are.” A second time the signal, “Water, water; send us water!” ran up from the distressed vessel, and was answered: “Cast down your bucket where you are.” And a third and fourth signal for water was answered: “Cast down your bucket where you are.” The captain of the distressed vessel, at last heeding the injunction, cast down his bucket, and it came up full of fresh, sparkling water from the mouth of the Amazon River. To those of my race who depend on bettering their condition in a foreign land, or who underestimate the importance of cultivating friendly relations with the Southern white man, who is their next-door neighbor, I would say: “Cast down your bucket where you are” — cast it down in making friends in every manly way of the people of all races by whom we are surrounded. Cast it down in agriculture, mechanics, in commerce, in domestic service, and in the professions. And in this connection it is well to bear in mind that whatever other sins the South may be called to bear, when it comes to business, pure and simple, it is in the South that the Negro is given a man’s chance in the commercial world.”

This message to the black worker is the same message Booker T Washington preached to his students all his years at Hampton and Tuskegee, which we have heard before:

“Our greatest danger is, that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labor and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life; shall prosper in proportion as we learn to draw the line between the superficial and the substantial, the ornamental gewgaws of life and the useful. No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top. Nor should we permit our grievances to overshadow our opportunities.”

In 1895 the whites had all the wealth, the whites had all the jobs, the whites controlled all the opportunities. This was his message to the white businessmen:

“To those of the white race who look to the incoming of those of foreign birth and strange tongue and habits for the prosperity of the South, were I permitted I would repeat what I say to my own race, “Cast down your bucket where you are.” Cast it down among the 8,000,000 Negroes whose habits you know, whose fidelity and love you have tested in days when to have proved treacherous meant the ruin of your firesides. Cast down your bucket among these people who have, without strikes and labor wars, tilled your fields, cleared your forests, built your railroads and cities, and brought forth treasures from the bowels of the earth, and helped make possible this magnificent representation of the progress of the South. Cast down your bucket among my people, helping and encouraging them as you are doing on these grounds, and to education of head, hand, and heart, you will find that they will buy your surplus land, make blossom the waste places in your fields, and run your factories. While doing this, you can be sure in the future, as in the past, that you and your families will be surrounded by the most patient, faithful, law-abiding, and unresentful people that the world has seen. As we have proved our loyalty to you in the past, in nursing your children, watching by the sick bed of your mothers and fathers, and often following them with tear-dimmed eyes to their graves, so in the future, in our humble way, we shall stand by you with a devotion that no foreigner can approach, ready to lay down our lives, if need be, in defense of yours, interlacing our industrial, commercial, civil, and religious life with yours in a way that shall make the interests of both races one. In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”

The closing paragraph applies when it was delivered in 1895, definitely not 125 years later, and it really should not have been applicable then, but the first task facing the blacks when they were first freed from slavery was earning a living decent enough that you could feed and clothe your family.

“The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremist folly, and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than of artificial forcing. No race that has anything to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized. It is important and right that all privileges of the law be ours, but it is vastly more important that we be prepared for the exercises of these privileges. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera house.”[13]

BOOKER T WASHINGTON AND FORGIVENESS

The entire life of Booker T Washington can be summed up in this Bible verse:

“Then Peter came and said to Jesus, “Lord, if my brother sins against me, how often should I forgive? As many as seven times?” Jesus said to him, “Not seven times, but, I tell you, seventy times seven.”[14]

Booker T Washington demonstrates with his life that we must forgive constantly, forgive without expecting or asking for apologies, forgive even those who threaten us bodily harm or constantly humiliate us, always forgiving silently. This was the extreme forgiveness he had to show during the troubled times in which he lived, he had to forgive seven hundred times seventy times, so we can only have to forgive seventy times seven times in our lives. Booker T Washington forgave not with weakness but in strength, he never sacrificed his personal dignity while forgiving much, he forgave humiliation with strength of character. Rarely did he show anger, rarely was he angry.

Hard work and industriousness can win over many enemies, but not all enemies. Hard work and industriousness are futile if you are never given a chance, but that is not the project of Booker T Washington, that is the project of WEB Dubois and succeeding black leaders. But hard work and industriousness usually brings good results when we are persistent and patient, especially when you are looking for a job.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tuskegee_University

[2] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 3.

[3] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 1.

[4] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 2.

[5] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 3.

[6] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 4.

[7] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 6.

[8] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 8.

[9] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 5.

[10] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 8.

[11] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 8-10.

[12] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 12.

[13] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 14, https://iowaculture.gov/sites/default/files/history-education-pss-areconstruction-atlanta-transcription.pdf .

[14] https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Matthew+18%3A21-22&version=NRSVCE

6 Trackbacks / Pingbacks