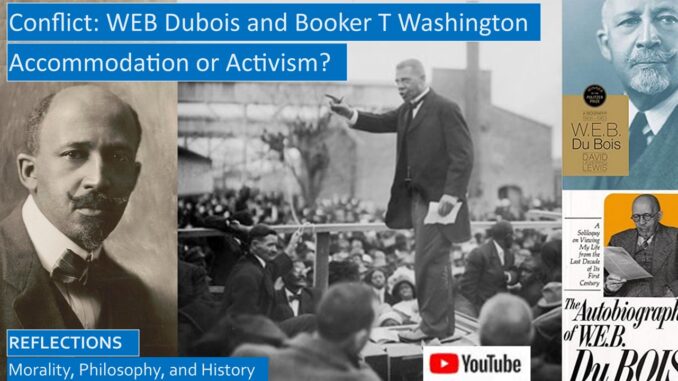

As WEB Du Bois, our contrarian activist leader, rose in prominence in the black civil rights movement, he came into conflict with the accommodationist Booker T Washington, founder of Tuskegee Institute. While Booker T Washington always encouraged blacks to be subservient and to work hard and save their pennies so that someday their lives will improve, WEB Du Bois demanded dignity, civil rights, and real economic opportunity for blacks.

Booker T Washington was an excellent administrator and delegator, he not only believed that the staff should help build the school, they should learn how to run the school also. When Tuskegee really started expanding, he would spend six months out of the year crisscrossing Northern cities, giving lectures and visiting philanthropists looking for additional funding for black colleges and his other projects.

Booker T Washington knew had to dwell on the positive, praising the many whites who supported black education, but not dwelling on the negative, including the many lynchings and humiliations and discriminations that dogged him and every black man of his era, so he could make a good impression of the moneyed white Northern philanthropists and businessmen.

YouTube video for this blog: https://youtu.be/Ntjl4xqQSfw

Script with Amazon book links: https://www.slideshare.net/BruceStrom1/conflict-between-web-dubois-and-booker-t-washington-accommodation-or-activism

Booker T Washington was harshly criticized by both WEB Du Bois and Ida B Wells for his accommodating position on lynchings, sometimes adopting the narrative that somehow the victims brought it upon themselves, or that they had improperly approached or molested white women, which was nearly always a lie, an all-too-common narrative by white supremacists.

Booker T Washington was always persistent and patient, and his persistence and patience paid off during the many years he spent fund-raising. Usually, the really large donations came from businessmen he had been calling on for many years. The businessman who donated five dollars this year might donate five thousand a few years from now, and fifty thousand in his will.[1]

The pinnacle of Booker T Washington’s fund raising and public relations efforts the Atlanta Exposition in 1895 that he helped to organize and promote, and where he delivered the keynote speech known as the Atlanta Compromise. This was the very first time a black man addressed such a large and influential body of white businessmen and white national politicians. All the major newspapers in the country promoted the Atlanta Exposition.

In his speech, Booker T Washington rhetorically addressed both the black worker and the white businessmen, but his real audience was the white businessman. He wanted to reassure him that the black workers were hard working and not too eager to rock the boat with talk about civil rights. [2] One of his fears was that the white employers might, instead of employing blacks, employ cheap Chinese workers, as was the practice in California.

But WEB Du Bois was not a party to this careful compromise between Booker T Washington and his wealthy donors. He wrote a newspaper article on Washington’s 1895 Atlanta speech, “There might be a basis for a real settlement between whites and blacks in the South, if the South opened to the Negroes the doors of economic opportunity and the Negroes cooperated with the white South in political sympathy. But this offer was frustrated by the fact that between 1895 and 1909 the whole South disenfranchised its Negro voters by unfair and illegal restrictions and passed a series of Jim Crow laws which demoted the Negro citizen to a subordinate caste.”[3]

The national debut of WEB Du Bois was his article in the Atlantic Magazine in 1897, Strivings of the Negro People, many of these thoughts would be repeated in the opening chapter of the Souls of Black Folk, entitled Of Our Spiritual Strivings, which included a criticism of the teaching and civil rights credos which Booker T Washington espoused.[4]

PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY AT ATLANTA UNIVERSITY

In 1898 WEB Du Bois accepted a position as head of the sociology department at Atlanta University. Tuskegee Institute and Howard University had been holding annual conferences on agricultural and trade issues for the rural blacks who attended these industrial schools, so the year before Du Bois was hired Atlanta University hosted annual conferences that were more centered on the needs of blacks who lived in cities.[5]

His biographer Lewis states that the “creed of the 1890’s,” as put forth by the Tuskegee trade school movement, “held that it was a dangerous conceit to expose black people to literature, history, philosophy, and ‘dead’ languages, thereby spoiling them for the natural order of southern society in which their place was a vote-less, industrious farmhands, primary school teachers, and occasional merchants.” But Atlanta University did not reject industrial training courses, but their industrial courses that were reinforced by liberal arts rather than undermined by them.”[6]

This struggle between the accommodationist Tuskegee machine and the activists was harming the funding sources of Atlanta University. WEB Du Bois explains, “Atlanta University from the beginning had taken a strong and unbending attitude toward Negro prejudice and discrimination; white teachers and black students ate together in the same dining room and lived in the same dormitories,” which also caused them to lose their annual land grant appropriation from the legislature. The state of Georgia also took issue with the University permitting the white students who were the children of their white professors attending school with black students.

Even though the industrial training in many black colleges, including Tuskegee, was often done by Atlanta graduates, WEB Du Bois said that the controversy between him and Booker T Washington “became more personal and bitter than I had ever dreamed, and which necessarily dragged in the University.” WEB Du Bois underestimated the vast influence of the Tuskegee machine when it interfered with his studies of the American Negro, and with the University’s fundraising. [7]

Why was the Tuskegee philosophy so popular with whites? WEB Du Bois believed that “this philosophy seemed to say that the attempt to over-educate a ‘child race’ by furnishing college degrees to its promising young people must be discouraged. In a world ruled by white people,” “the place of Negroes must be that of a humble, patient, hard-working group of laborers, whose ultimate destiny would be determined by their white employers.” College was for whites, elementary training and “training in farming and industry” was for blacks, “to make the mass of Negro laborers content with their lot and cheap to hire.”[8]

WEB Du Bois notes, “in 1903 Andrew Carnegie made the future of Tuskegee certain by a gift of $600,000.”[9] These were the years where the Tuskegee machine held the most influence, “Tuskegee became the capital of the Negro nation. Negro newspapers were influenced and finally the oldest and largest was bought by white friends of Tuskegee. Most of the other colored papers found it to their advantage not to oppose Mr. Washington, even if they did not wholly agree with him.”

WEB Du Bois resented this choking of criticism of Tuskegee, he also considered a job offer from Tuskegee. But he decided against it, he feared he would “sink to the level of a ghost-writer.”

There were efforts to repair the rift between them, they met several times. WEB Du Bois relates how different they were, he “was quick, fast-talking, and voluble,” while Booker T Washington was “wary and silent,” carefully measuring his words until he knew what his opponent’s wishes or desires were. IMHO, WEB Du Bois misinterpreted this cautious speech as suspicion.

In essence, WEB Dubois was accusing Booker T Washington of behaving like a salesman! Which indeed he was, he even has a chapter in his autobiography on sales techniques he honed from years of calling on white businessmen.

These efforts at reconciliation were dashed when he released his collection of essays, Souls of Black Folk, including a chapter “Of Mr Booker T Washington and Others.” WEB concludes this chapter: “So far as Mr Washington preaches Thrift, Patience, and Industrial Training for the masses, we must hold up his hands and strive with him, rejoicing in his honors.” “But so far as Mr Washington apologizes for injustice, North or South, does not rightly value the privilege and duty of voting, belittles the emasculating effects of caste distinctions, and opposes the higher training and ambition of our brighter minds,” “we must unceasingly and firmly oppose him.”

WEB Du Bois continues, “By every civilized and peaceful method, we must strive for the rights which the world accords to men, clinging unwaveringly to those great words” of our Founding Fathers, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”[10]

THE NIAGARA MOVEMENT AND THE TALENTED TENTH

WEB Du Bois compared the ideological differences between his Talented Tenth movement, that sought a liberal arts college education for the “Talented Tenth who through their knowledge of modern culture could guide the American Negro into a higher civilization,” to the belief by Booker T Washington that hard work and pinching pennies could eventually improve the lives of blacks. Whites could not always be trusted to provide this leadership to benefit the black race.

On the other hand, though Booker T Washington did not oppose college education for blacks, as his own children attended college, he proposed to emphasize training blacks in agriculture and the skilled trades. The problem is that blacks were unable to ever accumulate capital as long as the Jim Crow system exploited their labor.[11]

Accumulating capital is the phrase Booker T Washington and many white preferred. In many places, I substitute “pinching pennies” for “accumulating capital,” because if you are paid starvation wages, you cannot accumulate capital, you cannot even save your pennies.

Disenchanted with the Tuskegee leadership, in 1905 WEB Du Bois sent invitations to black leaders for a conference to be held at Niagara Falls, twenty-nine black leaders agreed on these principles for the Niagara Movement:

- “Freedom of speech and criticism.

- An unfettered and unsubsidized press.

- Manhood suffrage.

- The abolition of all caste distinctions based simply on race and color.

- The recognition of the principle of human brotherhood as a practical present creed.

- The recognition of the highest and best human training should not be monopolized by any class or race.

- A belief in the dignity of labor.

- United effort to realize these ideals under wise and courageous leadership.”[12]

FOUNDING THE NAACP

Although the idea of the NAACP did not originate with WEB Du Bois, he was invited to be one of the founding members. Attendance at the Niagara Conferences tapered off during the next few years, but in effect this movement merged with the NAACP, a new organization founded in 1909 by a group of white liberals and black leaders. WEB Du Bois was invited to join and became the editor of the movement’s magazine, The Crisis. When he joined the NAACP, he resigned from his professorship at Atlanta University, so their fundraising could be revived in his absence. WEB Du Bois was permitted the freedom to express his own opinions, as they were in general agreement with those of the NAACP. WEB Du Bois wisely refused to be the executive of this new organization, he knew he was a thinker and contrarian, not a manager.

WEB Du Bois said the NAACP organizing conference had “four groups:

- Scientists who knew the race problem.

- Philanthropists willing to help worthy causes.

- Social workers ready to take up a new task of abolition.

- Negroes ready to join a new crusade for their emancipation.”

Another important group that would form after their founding was the lawyers they hired to fight segregation.

WEB Du Bois would be the editor of the Crisis for twenty-four years, from 1910 through 1934. The circulation started at one thousand and climbed to one hundred thousand by 1918. In addition to the magazine, WEB Du Bois continued to publish his books. The NAACP slowly eclipsed the Tuskegee Machine in its influence among black leaders.

In his autobiography, WEB Du Bois says he was not eager to attack the efforts by Booker T Washington, but he does offer this valid criticism: “Mr Washington’s large financial responsibilities have made him dependent on the rich charitable public that” “he has been compelled to tell, not the whole truth, but that part of it which certain powerful interests in America wish to appear as the whole truth.”

Again, WEB Dubois was accusing Booker T Washington of being a salesman! Which he certainly was.

WEB Du Bois bemoans how, under the Democratic Wilson administration in 1915, a flood of racial discriminatory legislation is passed by Congress. Then he mentions, in passing, in mid-sentence, how Booker T Washington died that year.[13]

His biographer Lewis recalls WEB Du Bois’ farewell to Booker T Washington in the pages of the Crisis: “Washington’s death marked ‘an epoch in the history of America.’ He was the ‘greatest Negro leader since Frederick Douglass, and the most distinguished man, white or black,’ to emerge from the South since the Civil War. There was much to thank him for: Tuskegee, the ideal of interracial cooperation in the South, the encouragement of thrift and business among African Americans, the acquisition of land.”

But WEB Du Bois qualifies his praise of Booker T Washington, even in his obituary, “Stern justice commanded that ‘we must lay on the soul of this man a heavy responsibility for’ Negroes losing the right to vote, ‘the decline of the Negro college and public school, and the firmer establishment of color caste in this land.’”[14]

REFLECTING ON THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF BOOKER T WASHINGTON

In his autobiography, Up From Slavery, Booker T Washington does not mention his conflicts with WEB Du Bois, his rival’s name may not even appear in this work. Perhaps he was sensitive to some of his rival’s criticisms, he is careful that he champions black suffrage and stark opposition to lynching in his autobiography. The main theme is how blacks can improve their lot by gaining a valuable skillset, working hard, and not making waves by being good employees.

We like our biographer Lewis’ description of Booker T Washington’s Up From Slavery, “The story was vintage American: faith in God and hard, hard work overcoming bleakest adversity. The cast of edifying characters included an unlettered, devoted mother, aristocratic and kindly white families, the white matron who admitted him to Hampton after a parlor-sweeping examination, father-figure General Armstrong,” headmaster of Hampton University, his alma mater, “and his ‘gospel of the toothbrush,’ the visionary ex-slave property owner, Lewis Adams, who negotiated Tuskegee’s existence, Washington’s self-sacrificing wives, and good friend the wealthy Andrew Carnegie.”[15]

What is meant by the “gospel of the toothbrush?” Plantation slaves in the Deep South were treated like talking livestock, many slaves were only given one change of clothes a year, nobody gave their slaves toothbrushes.

Plantation slaves were not taught table manners because they had no room for tables in their one room dirt floor shacks, they ate in the field, and some cruel owners fed colored children like they fed their hogs, at the trough. But educated blacks, after Emancipation, were expected to have manners, so black colleges included courses on etiquette and table manners. Booker T Washington, who was himself a former plantation slave, appreciated these etiquette classes at Hampton University, and duplicated them at Tuskegee.

Our biographer notes that, behind the scenes, Booker T Washington funded many individual civil rights initiatives.[16] Thomas Sowell wrote this: “Booker T Washington privately not only supported efforts to safeguard civil rights but also wrote anonymous newspaper articles protesting the violation of those rights, as did his trusted agents.” “He secretly financed legal challenges to Jim Crow laws,” sometimes secretly paying the legal fees for black defendants.

Thomas Sowell continues, “Booker T Washington also worked behind the scenes to get federal appointments for blacks in Washington and postmaster appointments in Alabama, as well as lobbying Presidents to appoint federal judges who would give blacks a fairer hearing.”[17]

In other sources I have read that Booker T Washington secretly helped fund the NAACP, but this is not mentioned in the sources for this video. We do know that Booker T Washington was not interested in discussing his disagreements with WEB Dubois in his autobiography. Perhaps he anticipated that a new generation of black activist leaders could take a more activist stance, perhaps he simply wished that WEB Dubois had been born a decade or two later.

After the death of Booker T Washington, the Tuskegee Machine declined in influence, and WEB Du Bois’ NAACP became the leading civil rights organization. WEB Du Bois would live to his nineties, passing away four decades later in 1963. During this time, the country experienced two world wars, the depression, the Cold War, and the Civil Rights successes of the Fifties and Sixties.

DISCUSSION OF SOURCES:

We prefer reading the autobiographies of black civil rights leaders because we want them to speak for themselves. We especially enjoy reading WEB Du Bois’ descriptions of the many challenges he faced in his life, with surprising self-revelations. And likewise for Booker T Washington, his description of what life was like as a slave was captivating, as was his climb out of slavery to become one of the leading spokesman of blacks in the country, as well as his many close relationships with leading white businessmen and philanthropists.

The excellent biography by David Levering Lewis did provide interesting independent observations about his complex relationship with Booker T Washington and WEB Du Bois. For this phase of his life there are many sources, but he heavily relies on the two autobiographies.

Another important source is WEB Du Bois’ Soul of Black Folk, which includes many of the original autobiographical essays that are repeated in his autobiography.

[1] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 12.

[2] Booker T Washington, Up From Slavery, Chapter 14.

[3] WEB Du Bois, the Autobiography of WEB Du Bois (Canada International Publishers, 1968, 2007), p. 209.

[4] David Levering Lewis, Biography, WEB Du Bois (New York: Holt Paperback, 2009), pp. 143-145, and the Souls of Black Folk (New York: Dover publications, 1903, 1994), pp. 1-8, 25-36.

[5] WEB Du Bois, the Autobiography of WEB Du Bois, pp. 213-214.

[6] David Levering Lewis, Biography, WEB Du Bois, p. 155.

[7] WEB Du Bois, the Autobiography of WEB Du Bois, pp. 222-224 and David Levering Lewis, Biography, WEB Du Bois, p. 155.

[8] WEB Du Bois, the Autobiography of WEB Du Bois, pp. 230-231.

[9] WEB Du Bois, the Autobiography of WEB Du Bois, p. 238.

[10] WEB Du Bois, the Autobiography of WEB Du Bois, pp. 241-245 and WEB Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, p. 35.

[11] WEB Du Bois, the Autobiography of WEB Du Bois, p. 236.

[12] WEB Du Bois, the Autobiography of WEB Du Bois, pp. 248-249.

[13] WEB Du Bois, the Autobiography of WEB Du Bois, pp. 254-265.

[14] David Levering Lewis, Biography, WEB Du Bois, pp. 326-327.

[15] David Levering Lewis, Biography, WEB Du Bois, p. 183.

[16] David Levering Lewis, Biography, WEB Du Bois.

[17] Thomas Sowell, The Thomas Sowell Reader (New York: Basic Books, 2011), p. 282.

2 Trackbacks / Pingbacks