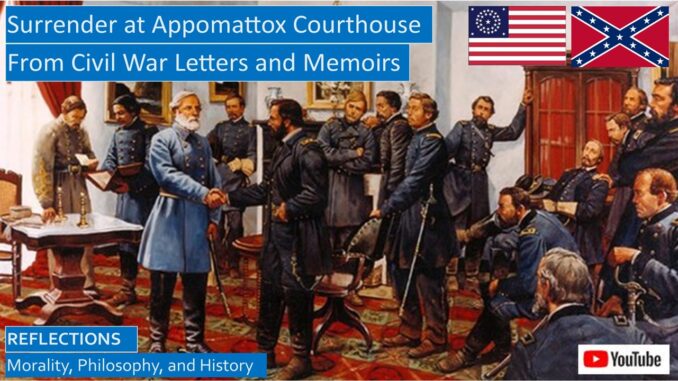

What happened when Robert E Lee surrendered his army to General Ulysses S Grant at the Appomattox Courthouse? Why were the Confederates forced to surrender? Were the Confederate forces and horses starving?

Why didn’t General Grant wear a dress uniform like Robert E Lee? Why did he refuse his sword?

What were the terms of surrender? Were the Confederates able to keep their horses for the next planting?

YouTube video for this blog: https://youtu.be/_Dr7qia6XkQ

THE TIDE OF WAR TURNS AGAINST THE CONFEDERACY

There were two theaters of war, the Western Theater, where the Union was mostly victorious, gradually winning control over the Mississippi Basin, and the more visible Eastern theater centered in Virginia, where the able Confederate General Robert E Lee won notable battles. In addition, the Union won victories in Tennessee and the border states, and the Union navy strengthened its blockade of Southern ports, capturing many port cities and coastal areas.

The tide of war decisively turned in favor of the Union on July 3rd, 1864, when General Grant prevailed in his long Siege of Vicksburg, which meant that the Union forces controlled the entire Mississippi River basin, beginning from the captured port of New Orleans, cutting off Louisianna and Texas from the rest of the Confederacy.

Siege of Vicksburg: Ordinary Union Soldiers and Generals Grant and Sherman Recount the Struggle

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/siege-of-vicksburg-ordinary-union-soldiers-and-generals-grant-and-sherman-recount-the-struggle/

https://youtu.be/U6KNO6IkVQs

Following several Confederate victories, General Robert E Lee took the war to Pennsylvania, hoping to gain recognition for the Confederacy from France and England, knowing that a victory might threaten the capitol of Washington, DC. He ordered the infamous Pickett’s Charge, decimating the Confederate infantry, leading to a devastating defeat on the same day as Vicksburg fell.

Gettysburg was the bloodiest battle of the war, over fifty thousand soldiers and many officers and generals lost their lives in three days of battle. While the Union forces could replace their losses, the Confederacy could not.

Gettysburg: Ordinary Soldiers and Generals Pickett and Longstreet Remember the Bloody Charges

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/gettysburg-ordinary-soldiers-and-generals-pickett-and-longstreet-remember-the-bloody-charges/

https://youtu.be/ibTm3l-C8VQ

After Vicksburg, Abraham Lincoln knew he had finally found a general who would not only deliver victories, but who would relentlessly pursue and grind down the Confederate Army until victory was achieved. Six months after Gettysburg and Vicksburg, General Grant was promoted to lead all the Union armies.

Confederate armies were engaged on all fronts. To damage the Confederate supply lines, General Sheridan devastated the farms in the Shenandoah Valley. General Sherman captured Atlanta and devastated the countryside of Georgia in his March to the Sea, then went north to devastate the Carolinas.

General Grant’s Army of the Potomac continually attacked Robert E Lee’s forces in bloody battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, sometimes losing, mostly winning, especially at the Battle of Five Forks, the Waterloo of the Confederacy, but always flanking the Confederates, forcing them to stretch their front lines. General Grant’s army broke the Confederate forces after the Siege of Petersburg, forcing the Confederate government and army to abandon the Confederate Capitol of Richmond, Virginia.[1]

Initially, I was not planning on reflecting on the Civil War battles, instead concentrating on emancipation and civil rights, but then I discovered how many paintings and lithographs existed of nearly every conflict of the Civil War, including paintings by Winslow Homer that captured the emotions of the nation during and after the war.

Civil War Through Paintings

https://youtu.be/2hoBOSOBUP8

HAMPTON ROADS AND TALK OF PEACE

Leaders on both sides were pressured to explore peace talks, leading to talks between President Lincoln, Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens, and other Union and Confederate officers on a steamboat in Hampton Roads, Virginia, discussing slavery, emancipation, and terms of surrender, but were unable to come to an agreement.[2]

In General James Longstreet’s memoirs, there is a chapter titled Talk of Peace, which is before the chapters on the Confederate defeats at the Battle of Five Forks and the Siege of Petersburg. During a meeting arranged between him and Union General Ord, they informally discussed peace initiatives. Longstreet remembers: “Referring to the recent conference of the Confederates with President Lincoln at Hampton Roads, he said that the politicians of the North were afraid to touch the question of peace, and there was no way to open the subject except through officers of the armies. On his side they thought the war had gone on long enough; that we should come together as former comrades and friends and talk a little.”

Longstreet’s memoirs continue, “General Ord suggested that the work as belligerents should be suspended; that General Grant and General Lee should meet and have a talk; that my wife, who was an old acquaintance and friend of Mrs Grant in their girlhood days, should go into the Union lines and visit Mrs Grant” with an escort of Confederate officers. “Then Mrs Grant would return the call under escort of Union officers and visit Richmond; that while General Lee and General Grant were arranging for better feeling between the armies, they could be aided by intercourse between the ladies and officers.”

What a bizarre proposal for a peace initiative! Civil War wives serving as diplomats! We doubt this was seriously discussed. What is certain is that Lee corresponded with Grant in March 1865 on possible peace initiatives and exchanges of prisoners of war.[3] Previous discussions on prisoners of war were inconclusive due to the Southern enslavement of black Union soldiers, denying them prisoner-of-war status.

Longstreet recalled in his memoirs that after the defeat at Petersburg, “we passed abandoned wagons and artillery caissons in flames.” “One of my battery commanders reports that his horses were too weak to haul his guns. He was ordered to bury the guns and cover them up with old leaves and brushwood. Many weary soldiers were picked up, and many came to the column from the woodlands, some with, many without, arms, all asking for food.”

The horses often suffered even more than the soldiers in the incessant campaigning in the last year of the war, as Grant’s armies sought to grind down the Confederate armies and destroy the agricultural base of the Confederacy. We learned this from a letter from a Union cavalry officer describing how the horses on both sides suffered and died from exhaustion and starvation in large numbers.

Horses and Cavalry from Xenophon in Ancient Greece to the American Civil War, and in New York City

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/horses-and-cavalry-from-xenophon-in-ancient-greece-to-the-american-civil-war-and-in-new-york-city/

https://youtu.be/lB6x-__GHy4

In early April 1865, an informal group of Confederate generals met and asked General Pendleton to inquire about peace with General Lee. Longstreet says he asked him whether he knew that “officers or soldiers who asked commanding officers to surrender should be shot.”

When he conferred with Robert E Lee, he responded: “The enemy does not fight with spirit, while our boys still do.” “We had sacred principles to maintain, and rights to defend, for which we were in duty bound to do our best, even if we perished in the endeavor.” Pendleton praised Robert E Lee: “Where his conscience dictated and his judgment decided, there his heart was.”

The last straw was when the Union forces captured a Confederate supply train. General Longstreet remembers: “General Sheridan was informed of four trains of cars at Appomattox Station loaded with provisions for General Lee’s army. He gave notice” to his cavalry “and rode twenty-eight miles in time for General George Custer’s army to pass the station, cut off the trains, and drive back the guard advancing to protect them. He helped himself to the provisions and captured besides twenty-five pieces of artillery and a wagon and hospital train.”

When General James Longstreet informed General Robert E Lee about the wretched condition of the Confederate armies, Lee responded: “There is nothing left me but to go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths. Is it right to surrender this army? If it is right, then I will take the responsibility.”[4]

GRANT SUGGESTS SURRENDER TO ROBERT E LEE

On April 7, 1865, after the capture of Richmond, General Grant wrote Robert E Lee: “The results of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia in this struggle. I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood, by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the Confederate States army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.”

That same day Robert E Lee replied, “Though not entertaining the opinion you express on the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia, I reciprocate your desire to avoid useless effusion of blood, and there, before considering your proposition, ask the terms you will offer on condition of its surrender.”

The next day, Grant advised Lee: “There is but one condition I would insist upon, namely: that the men and officers surrendered shall be disqualified for taking up arms again against the Government of the United States.”

Lee’s army was crumbling as many of his soldiers deserted to return home to their Virginia farms. He had planned to replenish his troops at Appomattox, but that supply train had been captured by Custer’s cavalry, and his armies were blocked from fleeing west to the Blue Ridge mountains to continue the fight. Robert E Lee set up a white flag to halt the fighting, sending Grant a note requesting a meeting near Appomattox Court House.

ROBERT E LEE SURRENDERS AT APPOMATTOX

Historians have long commented on how crisp General Lee’s uniform was at the surrender compared to the frumpy appearance of General Grant. Robert E Lee was expecting to be arrested and thrown in jail as a prisoner-of-war and wanted to surrender in a dignified uniform. On the other hand, General Grant thought it would be discourteous to keep Lee waiting, he did want to delay by going back to camp to change into a dress uniform. And indeed, a general on the battlefield in full dress uniform was a tempting target.

Grant remembers that day: “When I had left camp that morning, I had not expected” to meet with Lee “so soon,” “and consequently was in rough garb. I was without a sword, as I usually was when on horseback on the field, and wore a soldier’s blouse for a coat, with the shoulder straps of my rank to indicate to the army who I was.”

Grant continues, “General Lee was dressed in a full uniform which was entirely new, and was wearing a sword of considerable value, very likely the sword which had been presented by the State of Virginia. At all events, it was an entirely different sword from the one that would ordinarily be worn in the field. In my rough traveling suit, the uniform of a private with the straps of a lieutenant-general, I must have contrasted very strangely with a man so handsomely dressed, six feet high and of faultless form. But this was not a matter that I thought of until afterwards.”

Grant speculates in his memoirs: “What General Lee’s feelings were, I do not know. As he was a man of much dignity, with an impassible face, it was impossible to say whether he felt inwardly glad that the end had finally come, or felt sad over the result, and was too manly to show it. Whatever his feelings, they were entirely concealed from my observation; but my own feelings, which had been quite jubilant on the receipt of his letter, were sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, thought that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse. I do not question, however, the sincerity of the great mass of those who were opposed to us.”

Both Lee and Grant had attended West Point and had served under General Winfield Scott in the Mexican War in the 1840’s, as had many of the leading officers of both armies. They first engaged in small talk, General Lee said he recalled meeting Grant in that war, though this may have been a courtesy. General Lee then asked what the terms of surrender would be.

Robert E Lee ceremoniously offered his sword, but Grant refused it Grant wrote out the terms, which paroled the Confederates on the condition that they “would not take arms against the Government of the United States.” “The arms, artillery and public property are to be parked and stacked.” “This will not embrace the side-arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage. This done, each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by the United States authority as long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.” This meant that the Union would not hold any Confederate soldiers as prisoners of war.

Grant recalls that when General Lee “read over that part of the terms about side arms, horses, and private property of the officers, he remarked, with some feeling, I thought, that this would have a happy effect upon his army.” Lee pointed out that some Confederate cavalrymen and artillerists who were not officers provided their own horses, and if they could modify the terms to take this into account. Grant replied that although he would not modify the formal parole terms, he would instruct that all Confederates would be permitted to keep their horses.

In his memoirs, Grant showed compassion for the Confederates. “The whole country had been so raided by the two armies that it was doubtful whether they would be able to put in a crop to carry themselves and their families though the next winter without the aid of the horses they were then riding. The United States did not want them.” “Lee remarked again that this would have a happy effect.”

I have never read any explanation for why the officers were permitted to keep their sidearms. Were these sidearms intended to deter horse thieves?

Finally, as Grant remembers, “General Lee, after all was completed and before taking his leave, remarked that his army was in a very bad condition for want of food, and that they were without forage” for the horses, “that his men have been living for some days on parched corn exclusively, and that he would have to ask me for rations and forage.” He instructed Lee to send his quartermaster to the captured supply trains at Appomattox Station, that he could have all the provisions he needed. But he answered that even the federal horses had no fodder or hay, they could only graze on the grass in the fields.

The terms were similar to the terms offered to the Confederates surrendering after the Siege at Vicksburg, and at both Vicksburg and Appomattox, the Union soldiers were forbidden to celebrate publicly. Grant recalls: “When news of the surrender first reached our lines, our men commenced firing a salute of a hundred guns. I at once sent word, however, to have it stopped. The Confederates were now our prisoners, and we did not want to exult over their downfall.”

In Longstreet’s memoirs, he remembered that “as General Lee rode back to his army, the officers and soldiers” assembled “in anxious wait for the loved commander. From a force of habit, a burst of salutations greeted him, but quieted as suddenly as they arose. They were standing “with hats off, heads and hearts bowed down. As he passed, they raised their heads and looked upon him with swimming eyes. Those who could find voice said good-bye, those who could not speak, and were near, passed their hands gently over the sides of Traveller,” his horse. “Lee rode with his hat off, and had sufficient control to fix his eyes on the line between the ears of Traveller, and look neither to right nor left until he reached a large white oak tree, where he dismounted to make his last headquarters, and finally talked a little.”

When asked by Grant whether General Lee could influence the surrender of the other Confederate armies, he said that he could not do this without first conferring with the Confederate President, who had already fled south and was incommunicado. Generals Grant and Lee permitted the soldiers on both sides to visit their friends in the opposing armies.[5]

FIVE DAYS AFTER APPOMATTOX, LINCOLN IS ASSASSINATED

Sarah wrote her brother Jimmie, “A week ago today I wrote you that it was a day of rejoicing over victories achieved” when General Lee surrendered at Appomattox. “Today that joy is turned to sorrow. Last night the news reached us that Lincoln had been assassinated.”

“Today in church, while they were singing the second time, someone handed Minister Keely a paper announcing the death of Lincoln and Seward.” Secretary of State Seward eventually recovered from his assassination attempt. “It was the first the congregation had heard of their death. All had hoped they might live. I don’t think there was a dry eye in the church when he read it. His feelings so overcame him that he asked to be excused from preaching that morning. After a short prayer, the congregation was dismissed. It has cast a gloom over the entire north. All have felt the shock.”[6]

DISCUSSING THE SOURCES

Ulysses S Grant wrote his personal Civil War memoirs when he was on his deathbed to provide for his widow, this was a best-seller when originally published after 1885, and helps bring alive the many battles of the Civil War, reminding us that history when lived is not inevitable. Ron Chernow wrote an excellent biography of Grant in 2017, although Grant’s Memoirs were his main source for the events surrounding the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse. We also quoted from one Civil War Letter.

To defend his military reputation, since many former Confederates wanted to blame him for the Gettysburg defeat for political reasons, James Longstreet published his memoirs in 1896, using the information he gathered for Lee’s abortive memoirs. His memoirs are not as memorable as Grant’s memoirs, and he has few observations apart from a strict military history.

The closing chapter of Grant’s Memoirs reveals that immediately after Appomattox, Grant sent Sheridan’s Union troops to the Mexican border to protest French mischief in the New World, and also with his obsession to annex Santa Domingo, which today is the Dominican Republic, bordering Haiti.

Another major source we consulted was the Great Courses/ Teaching Company lectures on the Civil War by Professor Gary Gallagher. This is both a history of the Civil War battles and an account of the social and political conditions, both North and South, during the war.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Civil_War and Gary Gallagher, The American Civil War (The Great Courses, www.thegreatcourses.com, 2000)

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hampton_Roads_Conference

[3] James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox, Memoirs of the Civil War in America, Chapter XL, Talk of Peace, pp. 318-320.

[4] James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox, Memoirs of the Civil War in America, Chapter XLIII, Appomattox, pp. 336-339.

[5] The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S Grant, Chapter 67, pp. 721-727 and James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox, Memoirs of the Civil War in America, Chapter XLIII, Appomattox, pp. 340-343.

[6] Civil War Letters, From Home, Camp & Battlefield, edited by Bob Blaisdell (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2012), pp. 140-142.

3 Trackbacks / Pingbacks