Today we will reflect on the history of the legal struggles by the NAACP attorneys, mainly Thurgood Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston, that sought to dismantle the Jim Crow segregation and discrimination laws. We ponder:

How was the Supreme Court Brown v Board of Education decision, which ordered the desegregation of public schools, the culmination of decades of litigation?

What persuaded the Supreme Court to rule that the previously decided Plessy v Ferguson decision, which stated that Separate But Equal facilities for blacks and whites were acceptable, violated the Fourteenth Amendment?

How did the efforts to upgrade the premier black law school at Howard University enable black attorneys to further civil rights for blacks?

YouTube video for this blog: https://youtu.be/fBSNQXDziDU

YouTube script with more book links: https://www.slideshare.net/slideshows/naacp-attorneys-thurgood-marshall-and-charles-houston-challenge-jim-crow-in-the-courts/266298378

PUBLIC OPINION SLOWLY SHIFTS

Before the courts started to slowly turn away from segregation and the Jim Crow legal system, public opinion in the South had to shift, which happened ever so slowly. During Reconstruction, immediately after the Civil War, many whites joined the Ku Klux Klan and other white terrorist groups to keep the Negro down through violence and intimidation, and often lynchings and murders of blacks went unpunished. There were entire towns that resisted the federal Union troops sent into the South to guarantee the civil rights and voting rights of the freed slaves. Also, the 1619 Project features many horrid stories of the injustices blacks suffered in the Deep South before the Civil Rights Era of the Sixties.

Chaos of Reconstruction, Terror After the Civil War

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/chaos-of-reconstruction-terror-after-the-civil-war/

https://youtu.be/ZEX050eTn38

Terror During Reconstruction, White League Confronts General Longstreet and Union Army

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/terror-during-reconstruction-white-league-confronts-general-longstreet-and-union-army/

https://youtu.be/bF3w2RrSaM0

Critical Race Theory: Reviewing the 1619 Project and Beloved

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/critical-race-theory-reviewing-the-1619-project-and-beloved/

https://youtu.be/JRdnB0lqN5o

This Old Deep South White Christian Reflects on How To Teach Both Sides of Critical Race Theory

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/this-old-deep-south-white-christian-reflects-on-critical-race-theory/

https://youtu.be/lAa_jqL3S7I

This opposition to civil rights in the South was not monolithic. For example, the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, founded by the black leader Booker T Washington in 1881, initially relied upon funds raised from the local Alabama business community. It helped that Tuskegee was a university town that was more tolerant of blacks.

Up From Slavery: Autobiography of Booker T Washington

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/up-from-slavery-autobiography-of-booker-t-washington/

https://youtu.be/yxDnJ6sBoJc

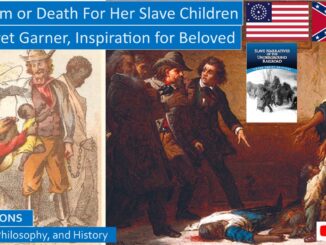

During the Reconstruction and the Jim Crow eras, lynching was so endemic in the South that often these gruesome events would be advertised in the newspapers, and body parts of the blacks who were lynched were sometimes displayed as souvenirs in store windows. It was rare for a Southern jury to ever convict a white man of even the most heinous crimes committed against a black man. If blacks called the sheriff to complain, often they were the ones arrested.

Ida B Wells, Journalist, Brave Woman, and Anti-Lynching Activist

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/ida-b-wells-journalist-brave-woman-and-anti-lynching-crusader/

https://youtu.be/sLDHs0AigvY

It was also common for Southern sheriffs to pick up young black men and charge them for vagrancy so their services could be sold to plantations, mines, the railroads, and other businesses as convict labor, which in many cases was even worse than slavery. Theodore Roosevelt’s Attorney General tried to combat this scourge, with minimal success. Afterwards, state investigations in Georgia and elsewhere eventually started turning public opinion, until the Justice Department under FDR during World War II started eliminating this inhuman treatment of black convicts, as Jim Crow was a propaganda coup for the Nazis.

Slavery By Another Name, Convict Labor in the Jim Crow Deep South

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/slavery-by-another-name-convict-labor-in-the-jim-crow-deep-south/

https://youtu.be/2TCXcEpohaM

By the twentieth century, black attorneys who volunteered their services to the NAACP started to chip away at the Jim Crow legal system. Thurgood Marshall’s devotion to the NAACP cases forced him to continue living at his parents’ home, as his practice had few paying clients. His mentor, Charles Hamilton Houston, convinced the NAACP to pay Thurgood a salary, they would be the only paid NAACP attorneys for many years, though by mid-century there were four other attorneys on staff, and there may have been more by the 1950’s. This bare-bones legal staff accomplished a great deal, winning many cases before the Supreme Court.

Although the black leader WEB Du Bois was a co-founder of the NAACP, he was not involved in the administration but was rather the editor of the Crisis magazine. He had little to do with the legal department, his name is not included in the index of the book we are reviewing, though our two NAACP attorneys often wrote articles for his Crisis magazine.

WEB Du Bois and the NAACP, Continuing the Fight For Civil Rights

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/web-du-bois-and-the-naacp-continuing-the-fight-for-civil-rights/

https://youtu.be/MNhkq69CIfo

HOWARD UNIVERSITY, PREMIER BLACK LAW SCHOOL

In 1929, Justice Louis Brandeis, the first Jewish man appointed to the US Supreme Court and an advocate for those abused under and by the law, ruefully told” Mordecai Johnson, “the president of Howard University, ‘I can tell most of the time when I am reading a brief by a Negro attorney. You have got to get yourself a real faculty out there or you’re always going to have a fifth-rate law school. And it’s got to be a full-time and a day school.’”

Johnson agreed. Although Howard University was the premier colored law school in the country, it was not accredited. If the attorneys graduating from Howard University were to have any chance in challenging the Jim Crow legal system, they had to be just as competent as their best white lawyers opposing them. He knew just the person who could make this leap, one of the most brilliant colored lawyers in the country, Charles Hamilton Houston.

Houston’s family was part of the Negro aristocracy of Baltimore, Houston’s father was an attorney who worked for the federal government before starting his own practice. They sent Houston to the school at Amherst, he was the only black student, graduating with honors. At Harvard Law School, he was the first African American member of the law review, earning an advanced law degree. Houston was appointed Assistant Dean, but he ran the day program since the white school dean taught at the night-school.[1]

As a first step, Charles Houston pressured lackadaisical professors to resign and replaced them with top-notch black attorneys. Then he tightened up the admission standards, accepting only blacks graduating from accredited colleges. Then in 1930 he made the big leap, seeking permission to close the night school.

Coming in the depths of the Depression, this was highly controversial. All the white professors resigned. Many of the black professors also protested; most of the alumni had attended night school; they did not want to “Harvardize Howard.” Johnson assigned the duties of the dean to Houston, who added tens of thousands of volumes to the student law library.

Half of the student body were not able to make the transition, many were unable to make the financial sacrifices necessary. Houston slipped money to some students who were struggling financially. But those who stayed became top-notch attorneys who could advance civil rights issues in the courts, who could be social engineers, who could “use the law to change the law.” Most importantly, in 1931, for the first time, the American Bar Association awarded Howard University Law School full accreditation and approval for the very first time.[2]

CHARLES HAMILTON HOUSTON AND THURGOOD MARSHALL TEAM UP

Dean Charles Houston became a mentor to the studious, hard-working Thurgood Marshall, who was top of the class. Our author, Rawn James, said that “in Houston’s presence, Marshall sparked like a match touched to flame. He admired the dean’s singular devotion to excellence, his contempt for good enough, and this admiration kindled within him these same traits.” He enjoyed repeating Houston’s maxim, “Lose your tempter, and you lose your case,” which was especially good advice for colored attorneys in those trying times. Another maxim was “Doctors can bury their mistakes, lawyers cannot.”[3]

Soon after graduating as valedictorian at Howard University, Thurgood Marshall accompanied Charles Houston on a fact-finding tour of the Deep South for the NAACP. This was a dangerous journey; many blacks were lynched in the Deep South.

Rawn James notes that “contrary to popular belief, most lynchings did not result from allegations of black men assaulting or even flirting with white women. Only sixteen percent of lynching victims were accused of sex crimes,” many “breached one of the South’s countless rules of racial etiquette.” There were “black women who were massacred at the rope, women like Mary Turner, who was seized in the Georgian night, strung up a tree by her ankles, sliced open with a buck-knife and forced to watch upside down as the men pulled her unborn baby from her screaming insides and killed it first.”

Houston later testified to Congress that “in 1933’s lynchings the most striking feature of nearly every press photograph is the number of women and little children present at the festivities.”[4]

Charles Houston spent more and more time on NAACP legal cases, as did Thurgood Marshall after he opened his private law practice. After several years, Houston left Howard on a leave of absence to work on the NAACP cases, and in time both he and Marshall Thurgood accepted a modest salary to become paid legal counsel for the NAACP.[5]

They worked closely together on many cases; Houston would be a mentor to Marshall until he passed away. However, Houston often sought to give credit to his brilliant understudy, allowing him to make public appearances, knowing that one day he would take over the reins of the NAACP’s legal struggle against the Jim Crow legal system. They were a resource for attorneys fighting for civil rights all over the country, Houston and Marshall would personally litigate only a small portion of the appeals for justice that were submitted to the NAACP.

BATTLING SEPARATE BUT EQUAL BY INSISTING ON EQUAL EDUCATION

Plessy v Ferguson was an NAACP test case in 1896 where Homer Plessy, a black man, bought a first-class railroad ticket, and was arrested when he refused to move to the blacks-only carriage, in violation of the state Jim Crow law. The majority Supreme Court opinion ruled that separate facilities for whites and blacks were permitted as long as they were equal. Justice Marshall Harlan wrote the famous dissenting opinion.

“The white race,” Harlan wrote, was undoubtedly the dominant race” in wealth, power, prestige, and achievements. However, the Constitution itself is color-blind. The thin disguise of equal facilities was not an innocuous separation of the races but is rather an expression of racial dominance rooted in slavery. The law assumed that blacks were “so inferior and degraded that they cannot be allowed to sit in proximity to white persons.” “In my opinion,” Harlan added, “the judgement this day rendered will, in time, prove to be as pernicious as the Dred Scott opinion.”

Justice Harlan correctly predicted that the decision would unleash a flood of statutes segregating every realm of Southern life. In fact, segregated facilities were almost never equal. [6]

Second Founding: The Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution, by Eric Foner

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/second-founding-the-reconstruction-amendments-to-the-constitution/

https://youtu.be/UciDV5laOLg

In the early part of the twentieth century, the NAACP did not battle segregation. The issues that took precedence were opposing lynching, improving due process and voting rights for blacks, and improving the economic conditions of blacks.

WEB Du Bois and the NAACP, Continuing the Fight For Civil Rights

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/web-du-bois-and-the-naacp-continuing-the-fight-for-civil-rights/

https://youtu.be/MNhkq69CIfo

Houston and Marshall agreed to take up the case of Donald Gaines Murray who had graduated from the mostly white Amherst College and had applied to the University of Maryland School of Law in 1934. He was eminently qualified but was rejected solely because they did not accept Negro applicants, violating the Fourteenth Amendment. They said blacks could instead apply to attend Princess Anne Academy, which had no law school and mostly high-school level classes. Marshall argued that since a law school for blacks did not exist in Maryland, the Plessy precedent dictated that Murray be permitted to attend the University of Maryland School of Law, and the local judge agreed, ordering that Murray be allowed to attend.

The university appealed, and the Appellate Court ruled in Murray’s favor, which meant that Marshall could not appeal the case to the US Supreme Court, which meant that this case would not create federal precedent. Murray graduated from law school and got along with both school officials and his fellow white students.[7]

In an article in the NAACP Crisis magazine, Houston explained they were demanding:

- “Equality of school terms.

- Equality of pay for Negro teachers.”

- “Equality of transportation for Negro school children at public expense.

- Equality of building and equipment.

- Equality of per capita expenditure for education of Negroes.

- Equality in graduate and professional training.”[8]

Marshall would represent William Gibbs, serving as both teacher and principal of Rockville Colored Elementary School in Maryland, who was paid less than half of his fellow white teachers. He petitioned for equal pay in 1936. A Maryland court held in favor of Gibbs, and the county announced that it would equalize the salaries of black and white teachers and principals over two years, since the county had to raise revenues for these raises. Although this did not set federal precedent, it made equal salaries more palatable without overturning the entire Jim Crow legal system.[9]

In Missouri, Lloyd Gaines applied to the Missouri School of Law and was at first accepted, but was then rejected when the registrar, SW Canada, learned that Lloyd was black, advising him to either attend the colored Lincoln University, which had no law school, or enroll in a school in another state with Missouri reimbursing his tuition. This was inherently unequal, in part because an out-of-state law school would not teach Missouri law. Houston decided to file the case seeking to have Gaines admitted to the law school as Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, emphasizing that he was really representing the interests of all blacks in Missouri.

When the court hearing commenced, there were few blacks witnessing the trial, since several lynchings deterred many from attending. But unlike in Maryland, in Missouri both the local and appellate court ruled in favor of the law school, arguing that Plessy sanctioned the separation of the races in all circumstances.

The case was appealed to a US Supreme Court where FDR had appointed several judges sympathetic to civil rights. The Gaines case set a valuable precedent, stating that Missouri could not shift its responsibility to furnish equal facilities and opportunities to its citizens to other states, ruling that he should be admitted to the Missouri School of Law.

Our author Rawn James notes that “Gaines weakened the holding of Plessy v Ferguson in two crucial respects:

- First, Gaines demonstrated that the Court no longer would defer to southern states’ dubious claims of providing an equal education for their black and white citizens; the chief justice’s opinion made clear that the judiciary henceforth would closely examine whether a defendant-state provided equal education to its residents regardless of race.

- Second, by declaring that Gaines’ educational right to be a ‘personal one,’ the justices preempted any state’s claim that it need not establish a substantially equal school for one or two black students.”

Sadly, Lloyd Gaines was having a difficult time supporting himself and was receiving death threats. While he was preparing to attend Missouri School of Law, he disappeared in New York City. His body has never been found. But his portrait now hangs on the wall of the Missouri School of Law.[10]

FIGHTING LILY WHITE JURIES AND RACIAL INJUSTICE

When a white man who had been threatening black women about town was killed in Paducah, Kentucky, in 1938, the police arrested a nineteen-year-old black youth named Joe Hale, who vigorously protested his innocence. His lawyers filed to quash his indictment because the county had excluded blacks from jury duty for fifty years. The account suggests the evidence tying him to the crime was scanty.

When both the local court and the appeals court ruled against Joe Hale, Houston appealed the decision in Hale v Kentucky to the US Supreme Court. As Rawn James notes, “Joe Hale’s murder conviction was overturned, and the Supreme Court’s unequivocal language left no room for obfuscation: The Constitution did not allow courts to exclude eligible citizens from jury service on account of race.”[11]

In another 1938 case in Montgomery, Alabama, two white sisters were beaten horribly while picking flowers, and one of them later died. The police immediately swept through the adjoining black neighborhood searching for suspects, they arrested Dave Canty based on the testimony of a fortune-teller seeking the reward offered by the governor. When he protested his innocence, they whipped and starved him in an isolated cell in prison until he confessed.

The author notes that this was progress, in prior decades he would have simply been lynched. At trial, he protested his innocence, saying he never met these white women, and that he confessed only because he had been beaten and starved for a week. He was convicted and sentenced to death; this sentence was upheld by the Alabama Supreme Court. Thurgood Marshall appealed to the Supreme Court, which ruled that confessions extracted by beatings were inadmissible evidence and ordered that the case be retried. This time he was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison, where he died many years later.[12]

In a prior ruling, the Supreme Court had ruled in Grovey v Townsend that a whites-only Democratic primary in Texas did not violate Texan’s right to vote because the Democratic Party preventing Negroes to vote in the primary was not an act of the state. The Supreme Court proclaimed this was wrongly decided in an appeal filed by Marshall in Smith v Allwright that excluding Negroes from voting in the primary elections was an act of the state, especially since there was not meaningful competition in the general election.

By the mid-1940’s, our author Rawn James notes that “Thurgood Marshall was engaged in a subtle dialogue with the Supreme Court. The justices knew him, his astute deference and easy insistence, and he had come to understand them.” “By their questions, asked and unasked, they told him their concerns and advised him where and how they were willing to step next.”[13] Although Houston still worked on NAACP cases, and although Marshall often asked his advice, he had returned to private practice a few years before, he would pass away in 1950, before the Supreme Court issued its Brown decision.

RACIAL RESTRICTIONS IN DEED COVENANTS NOT ENFORCEABLE

Spotwood Robinson, a student attending Howard Law School, wrote a thesis arguing that racist restrictive deed covenants, which forbade selling homes or real estate to Jews or blacks that neighbors found objectionable, should become unenforceable. His study included “data on the actual effects of racist covenants: how they skewed neighborhoods and cities.”

Thurgood Marshall was impressed and commissioned him to expand the argument for use in litigation in 1944. Marshall was coordinating as best he could the efforts of three dozen attorneys filing cases attacking these restrictive covenants across the country; he convened a meeting in Chicago of anti-covenant lawyers in 1945.

Two cases where neighbors sued to block the sale of homes to blacks, and where the state courts ruled for the restrictive covenants, were appealed to and consolidated by the Supreme Court, one of them was Houston’s case, Hurd v Hodge. Three of the justices recused themselves from the case because their houses were subject to these racially restrictive covenants. The Truman Administration filed a brief supporting the NAACP’s position.

These covenants were not mere private transactions immune from public scrutiny. Rawn James notes that “Marshall contended that state action commenced when buyers and sellers entered into a contract because the force of their agreement depended on judicial enforcement of the contract.”

The Supreme Court ruled unanimously “that in granting judicial enforcement of the restrictive covenants,” “the states have denied petitioners the equal protection of the law.” These petitioners “had been denied rights of ownership or occupancy enjoyed” “by other citizens of different race or color.” This violated the Fourteenth Amendment.[14]

BROWN DECISION, DESEGREGATION IN PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Quite often when the Supreme Court ruled in favor of civil rights for blacks, many states ignored the rulings, which led to appeals on issues that were already settled, which tried the patience of the justices. In some cases, cities simply closed pools and parks rather than integrate them. When a lawsuit was filed in Missouri by a black seeking entry to the white college School of Journalism, the state legislature shut down both the white and black Schools of Journalism.[15] Many state legislatures in the Deep South belatedly sought to appropriate more funds for black schools, pools, libraries, and parks, but the facilities were far too unequal, so these efforts were often far too little, far too late.[16]

The case that likely paved the way for overturning the Separate But Equal Plessy doctrine was the Oklahoma case, McLaurin v Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education. George McLaurin had sought a doctorate degree in Education but was not only denied admission because he was black, they also did not offer comparable in-state education for blacks.

When a federal judge ruled in his favor, the state reluctantly admitted George into its program, but insisted on humiliating him. The school officials forced him to sit in the hallway so segregation of the races was maintained, he had his own grim area in the cafeteria, and could only work at a desk hidden away from him when he used the library.

The NAACP appealed his case to the Supreme Court. The lawyers in Texas stated that Marshall’s brief did not cite any case contesting the Plessy Separate But Equal doctrine, because there were no opposing cases. The Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the University of Oklahoma cease humiliating George McLaurin. But the Chief Justice refused to overturn Plessy.[17]

Now was the time to end segregation once and for all, Thurgood Marshall announced to a key meeting of the members and attorneys of the NAACP in 1950. In future cases involving public schools, he planned to use a psychological study compiled by Kenneth Clark. In this study, foot-tall dolls, two brown, two white, were presented to black children aged three to seven.

Rawn James recollects that “the Clarks instructed each black boy or girl: ‘Give me the doll you like to play with;” then the nice doll, and then the dolls that is a nice color. Black children across the country displayed an “unmistakable preference for the white doll and a rejection of the black doll.” When he asked one black boy which doll he didn’t like, “he pointed at the brown doll,” “and he blurted, ‘That’s a nigger, I’m a nigger.’” Dr Wikipedia discusses the doll test in detail in its page on Kenneth and Mamie Clark.

The NAACP was appealing several cases, including blatant inequalities in South Carolina and Virginia public schools. But Marshall also chose to appeal a case in Topeka, Kansas, Brown v Board of Education, because Topeka had arguably equal school facilities for blacks and whites. Marshall would instead argue that black segregation itself harmed the black schoolchildren. These cases were consolidated by the Supreme Court.

Chief Justice Fred Vinson scheduled oral arguments for December 1952, but the justices were hopelessly fractured, Vinson did not want to abandon Plessy. A second round of oral arguments were scheduled for December 1953, but Chief Justice Fred Vinson died of a heart attack in September.

After attending his funeral, Justice Felix Frankfurter quipped to a friend, “This is the first indication I have ever had that there is a god.”

President Eisenhower appointed long-time Republican Earl Warren as Chief Justice, he later said this was his life’s “biggest damn fool mistake.” Earl Warren convinced his fellow justices that this needed to be a unanimous decision. Warren said this, summarizing the court’s opinion, “Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other tangible factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does.”[18]

John F Kennedy nominated Thurgood Marshall to be a judge on the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1961. His successor, Lyndon Baines Johnson, appointed him to be the Solicitor General in 1965, and then appointed Marshall to the Supreme Court in 1967, where he would serve until 1991. He was familiar to the justices since he presented oral arguments before the Supreme Court on many prior occasions.[19]

Even though many Northern and Border States complied with the Brown decision, resistance was widespread in the South, in Little Rock the public schools were closed for a year. Eisenhower had federalized the state National Guard to protect the black students selected by the NAACP to desegregate Little Rock High School. On the day of the Brown decision, black teachers warned their students to go home as soon as possible. This was a warning worth heeding, as an angry white man was prevented from raping one of these future Little Rock students that day.

American Civil Rights History: Yale Lecture Notes

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/american-civil-rights-history-yale-lecture-notes/

Civil Rights Era, Sixties and Beyond: Yale Lecture Notes

https://youtu.be/GQesHoV5IdI

In the Brown decision, the Supreme Court had signaled that it sought to promote civil rights and dismantle the remaining remnants of the Jim Crow segregation laws. This decision enabled the protest movements publicized by Martin Luther King.

To adequately understand the Civil Rights Struggle, you should view it from the perspective first of the lawyers, including Thurgood Marshall, who enabled

Martin Luther King, Youth and Schooling, Lewis’ Biography Chapters, 1 and 2

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/martin-luther-king-youth-and-schooling-lewis-biography-chapters-1-and-2/

https://youtu.be/_64FMZ6AlEg

Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks, Montgomery Bus Boycott, Lewis’ Biography, Chapter 3

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/martin-luther-king-and-rosa-parks-montgomery-bus-boycott-lewis-biography-chapter-3/

https://youtu.be/TuiyFycWE-U

Martin Luther King, Lunch Counters, Freedom Riders, and Albany, Lewis’ Biography Chapters 4-6

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/martin-luther-king-lunch-counters-freedom-riders-and-albany-lewis-biography-chapters-4-6/

https://youtu.be/_TLt2fQqL4w

Martin Luther King, Birmingham, Nonviolent Protests v Bombs and Brutality, Biography Chapter 7

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/martin-luther-king-birmingham-nonviolent-protests-v-bombs-and-brutality-biography-chapter-7/

https://youtu.be/5y0v0tYMdy8

Comparing MLK’s Letter from Birmingham Jail with Hannah Arendt’s Banality of Evil in Nazi Germany

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/comparing-martin-luther-kings-letter-from-the-birmingham-jail-with-hannah-arendts-the-banality-of-evil/

https://youtu.be/PqFAUEXbi8k

Martin Luther King, I Have a Dream Speech, March on Washington DC, Biography Chapter 8

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/martin-luther-king-i-have-a-dream-speech-march-on-washington-dc-biography-chapter-8/

https://youtu.be/IJ64y3nQA4Q

Martin Luther King, Bloody Struggles in Mississippi and Selma, Lewis’ Biography Chapters 8-9

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/martin-luther-king-bloody-struggles-in-mississippi-and-selma-lewis-biography-chapters-8-9/

https://youtu.be/eMA_7vLYcdM

Martin Luther King & LBJ: Great Society, Vietnam, Chicago & Memphis, Lewis Biography Chapters 10-12

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/martin-luther-king-lbj-great-society-and-vietnam-northern-civil-rights-biography-chapters-10-12/

https://youtu.be/IeKssG8mrlk

Martin Luther King, Summary of Biography by David Levering Lewis

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/martin-luther-king-summary-of-biography-by-david-levering-lewis/

https://youtu.be/XtdVGx2C3Cc

Martin Luther King conferred often with President Lyndon Baines Johnson, and they coordinated their activities to enable the passing of the Great Society legislation that furthered civil rights, voting rights for blacks, and enacted programs to fight poverty.

Lyndon Baines Johnson, Youth, Schooling, and Rise to Power

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/lyndon-baines-johnson-youth-schooling-and-rise-to-power/

https://youtu.be/hBYD1yDo9eE

Presidency of Lyndon Baines Johnson, Civil Rights, Great Society, and Vietnam War

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/presidency-of-lyndon-baines-johnson-civil-rights-great-society-and-vietnam-war/

https://youtu.be/lydW8mfpJGQ

DISCUSSING THE SOURCES AND CONCLUSIONS

Rawn James’ Root and Branch is an excellent history of the decades-long legal struggle against Jim Crow segregation and discrimination. He includes interesting short biographies of Charles Houston and Thurgood Marshall. There were several instances where his life was in some danger, though they do not have any personal experience with attempted lynchings.

What struck me was how stubborn many in the Deep South clung to the Jim Crow segregation system, many of the lawsuits I described had to be fought multiple times when many politicians and policemen in the Deep South simply ignored the Supreme Court decisions. Also included were discussions about NAACP’s battles against lynching. In the closing pages we learn that when more conservative judges were appointed to the Supreme Court, Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote many dissenting opinions for cases that rolled back some of the civil rights reforms.

[1] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2010), Chapter 2, Ambitious, Successful, Hopeful Dreams, pp. 16-24.

[2] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 3, No Tea for the Feeble, pp. 30-35.

[3] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 4, The Social Engineers, pp. 50-54.

[4] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 5, South Journey Children, pp. 55-57.

[5] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 6, The Law Offices of Thurgood Marshall, Esq., pp. 59-64.

[6] Eric Foner, The Second Founding (New York: WW Norton & Company, 2019), pp. 160-164.

[7] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 7, Murray v. Maryland, pp. 65-78.

[8] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 8, Don’t Shout Too Soon, p. 86.

[9] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 9, Special Counsel and Assistant Counsel, pp. 95-97, 101-102.

[10] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 10, On the Cusp in Missouri, pp. 103-122.

[11] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 12, Hope Looms, pp. 138-140.

[12] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 13, Marshall at the Helm, pp. 157-159.

[13] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 15, War at Home and Abroad, pp. 186-187.

[14] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 16, Supreme Broken Covenant, pp. 189-198.

[15] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 13, Marshall at the Helm, p. 151.

[16] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 18, Marshall at the Helm, p. 220.

[17] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 17, Peace of Mind, pp. 210-214.

[18] Rawn James, Jr., Root and Branch, Chapter 17, Root and Branch, pp. 219-235 and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kenneth_and_Mamie_Clark .

2 Trackbacks / Pingbacks