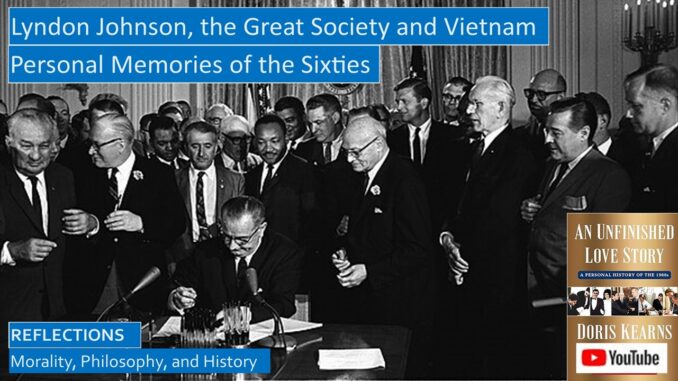

Why does Lyndon Baines Johnson have such a mixed legacy today?

How was LBJ able to pass so much legislation establishing the Great Society?

What was his working relationship with the Civil Rights activist Martin Luther King? How did King’s assassination, and the riots that followed, affect the passage of Civil Rights legislation?

Why didn’t Johnson end the War in Vietnam?

The YouTube video for this blog: https://youtu.be/MgVEipHdvfM

GOING THROUGH OLD BOXES OF MOMENTOUS MOMENTOS

During the Sixties, Doris Kearns was a White House intern, and then joined the staff, under LBJ, while Richard Goodwin was a speechwriter for JFK and LBJ, leaving shortly before Doris arrived. Doris spent many weekends and holidays at LBJ’s ranch in Texas after he retired from the Presidency. She wrote the definitive Johnson biography, which was more of an autobiography due to her extensive discussions with LBJ, starting with his boyhood and rise to power.

Lyndon Baines Johnson, Youth, Schooling, and Rise to Power

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/lyndon-baines-johnson-youth-schooling-and-rise-to-power/

https://youtu.be/hBYD1yDo9eE

She reflected on his Presidency, how he and Martin Luther King formed a partnership as they fought for greater Civil Rights, how he shepherded the legislation enacting the Great Society programs through Congress, and how the escalating War in Vietnam harmed his efforts and his legacy.

Presidency of Lyndon Baines Johnson, Civil Rights, Great Society, and Vietnam War

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/presidency-of-lyndon-baines-johnson-civil-rights-great-society-and-vietnam-war/

https://youtu.be/lydW8mfpJGQ

Dick was a widower when he finally met Doris at Harvard, proposing to her in 1972. Since his primary loyalty was to the Kennedys, and her primary loyalty was to Johnson, they would occasionally gently spar about their competing legacies.

Dick had hundreds of boxes of momentos documenting mixed memories they sifted through when he was in his eighties. Dick would pass away from cancer at 86 before she finished their Unfinished Love Story.[1] In part, it is unfinished because many of the legacies of the Great Society are still being challenged today.

LYNDON JOHNSON IS SWORN IN AS PRESIDENT

Three years into his presidency, John F Kennedy was suddenly cut down by an assassin’s bullet in Dallas, Texas. With Jackie Kennedy at his side, his Vice President, Lyndon Johnson, was quickly sworn into office on Air Force One, the Presidential plane.

We previously reflected on how the first few years of JFK’s administration were dominated by the Bay of Pigs disaster and the harrowing Cuban Missile Crisis, when the world feared a nuclear war would erupt with communist Russia. John F Kennedy belatedly supported a Civil Rights Bill that was stuck in Congress.

John F Kennedy, Cuba, Russia, and Civil Rights, Book Review of An Unfinished Love Story

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/john-f-kennedy-cuba-russia-and-civil-rights-review-of-an-unfinished-love-story/

Lyndon Johnson reminisced to Doris Kearns that after the assassination of John F Kennedy: “We were like a bunch of cattle caught in the swamp, unable to move to either direction, simply circling round and round. I understood that. I knew what had to be done. There is but one way to get the cattle out of the swamp. And that is for the man on the horse to take the lead, to assume command, to provide direction. In the period after the assassination, I was that man.”

LYNDON JOHNSON ADDRESSES THE NATION

Five days after JFK’s assassination, Lyndon Johnson addressed Congress and the nation, speaking of Kennedy’s domestic dreams, “the dream of education for all our children, the dream of jobs for all who seek them and need them, the dream of care for elderly, the dream of an all-out attack on mental illness, and above all the dream of equal rights for all Americans, whatever their race or color.”

Johnson emphasized, “No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy’s memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long. We have talked long enough in this country about equal rights. We have talked for one hundred years or more. It is time now to write the next chapter, and to write it in the books of law.”

Dick reminisced, “Impressive, a huge risk at the time. LBJ knew the path he was taking would cut him off from the southern bloc that was his heritage, isolate him from his oldest friends, and might well not succeed. But he was willing to take the path.”

LBJ challenged Dick, his new speechwriter, who coined the phrase, the Great Society. “It is not enough to just pick up the Kennedy program. We’ve got to use the Kennedy program to take on Congress, summon the states to new heights, create a Johnson program, different in tone, fighting and aggressive.” “Don’t worry about whether it is too radical or if Congress is ready for it.” “Everyone, deep down, wants something a little better for his children, everybody wants to leave a mark, something he can be proud of. And so do I. You, too, Bill and you, Dick. Well, now is your chance.”[2]

LBJ PASSING THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964

The first item on his agenda was passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that was stuck in Congress when JFK was assassinated. Before he was recruited to be Vice President, Lyndon Johnson was probably the most effective Senate Majority Leader in the twentieth century. He was an expert in shepherding legislation through Congress, keeping tabs on every Senator’s view and vanities.

Goodwin remembers, “Once signed,” the Civil Rights Act of 1964 “would outlaw the legal system of segregation that had provided the underpinnings of daily life in the South for seventy-five years. Jim Crow laws prohibited blacks from entering and eating in white-only restaurants, from sharing drinking fountains, bathrooms, and pools, hotels and motels, and concert halls. Overnight the new law of the land would begin to erase many of the indignities of the deep-seated system of segregation. The provisions of the bill would take effect immediately upon signing.”

At the signing ceremony, LBJ delivered this speech:

“We believe that all men are created equal. Yet many are denied equal treatment.

We believe that all men have certain inalienable rights. Yet many Americans do not enjoy those rights.

We believe that all men are entitled to the blessings of liberty. Yet millions are being deprived of these blessings, not because of their own failures, but because of the color of their skin.

But it cannot continue. Our constitution, the foundation of our Republic, forbids it,” “morality forbids it. And the law I will sign tonight forbids it.”

But after the signing, LBJ was in a melancholy rather than a festive mood. Johnson told Bill Moyers, “I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come.”

LBJ REELECTED IN PRESIDENTIAL LANDSLIDE OF 1964

The nomination of the ultra-conservative Barry Goldwater as the Republican candidate for President solved the Bobby problem for Johnson, enabling him to select Hubert Humphrey rather than Bobby Kennedy for Vice President. There was bad blood between Bobby and Johnson.

But Bobby refused to bow out of the race, but LBJ found a clever political solution. He delivered a televised statement at the Democratic Convention saying that it would be inadvisable for current Cabinet officials to run for Vice President, so they could concentrate on their duties, which included Bobby Kennedy, who was still the Attorney General.

Goodwin remembered that during the campaign, Johnson repeatedly pointed out that “while a minority still says NO, the overwhelming majority says YES to the policies he was proposing: a minimum wage, rights of the workingman, better education for our young, hospital care for our aged, a war on poverty, and equal rights for all.”

Johnson was reelected in 1964 by a landslide. “He had won by more than 15 million votes, 61 percent of all the votes cast. He had earned the mandate he sought to build the Great Society.”[3]

RAPIDLY PASSING THE GREAT SOCIETY LEGISLATION

With his landslide victory assured, LBJ prepared to seize the moment to pass as much Great Society legislation as possible. Goodwin recalls that a legislative “factory was assembled to investigate and produce landmark legislation on medical care, economic opportunity, education, the environment, the cities, immigration, housing and urban development, the arts, and much more that would alter the social, economic, and political landscape of the country.” “The massive problems of the cities” “resulted in a call for a new Department of Housing and Urban Development,” or HUD.

Goodwin continued: “LBJ instructed his task force to set goals ‘too high rather than too low.’ Final reports were to reach his desk around Election Day. It was imperative that the administration be prepared to move forward on the first day.” “LBJ resolved to deliver messages to Congress on Tuesdays and Thursdays, to allow briefing sessions on Mondays and Wednesdays for key members of Congress.” LBJ used his powers of persuasion honed when he was Majority Leader of the Senate to cajole congressmen to pass his legislation.

Much of this legislation was drafted with input from civil rights leaders, Martin Luther King in particular. Dick exclaimed: “They were in cahoots from the start.” Unlike Kennedy, who King had to persuade, LBJ was the initiator of the Civil Rights legislation. LBJ coordinated his legislative efforts with King’s protests that were publicizing the need for Civil Rights legislation.

Kennedy and Johnson’s relationship with Martin Luther King differed. Kennedy was not resolutely dedicated to passing Civil Rights legislation but was more likely to bail out King when he was sitting in a dangerous Jim Crow jail. Johnson was the opposite: while he doggedly pursued civil rights legislation, he would let King twist in the wind when he knew that the sympathy invoked by his suffering would increase the chances of passing the legislation they both desired.

MARCH AT SELMA AND VOTING RIGHTS LEGISLATION

Political calculations were made. Goodwin remembers: “Though King was in Alabama, organizing what was then his top priority, the coordinated drive to register black voters, he did not want to bring up voting rights. He knew that the president believed that voting rights should be addressed later so they would not lose southern support for federal aid to education, Medicare, poverty, and the cities.”

But in Selma, Alabama, the news crews were about to broadcast live to the living-room television sets of millions of Americans unimaginable scenes of police brutality against negroes who were peacefully protesting to gain the right to register to vote.

Martin Luther King, Bloody Struggles in Mississippi and Selma, Lewis’ Biography Chapters 8-9

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/martin-luther-king-bloody-struggles-in-mississippi-and-selma-lewis-biography-chapters-8-9/

https://youtu.be/eMA_7vLYcdM

Goodwin recalls: “Sheriff Clark and a squad of twenty nightstick-wielding state troopers launched a brutal attack against a peaceful voting rights march, sending the protesters, including young Jimmie Lee Jackson, his mother, and eighty-two-year-old grandfather, fleeing for safety. The troopers chased Jackson and his family into a café where they beat him as he tried to protect his mother, then shot him twice in the stomach and dragged him into the street. He died eight days later.”

In response, Martin Luther King and the protesters planned to march from Selma to Montgomery to present to Governor Wallace a demand to end police brutality and voter suppression. Tens of millions of Americans watched as they “reached the crest of the bridge” at Selma, where “a wall of helmeted state troopers,” some with gas masks, some on horseback, “blocked their way.”

Goodwin recalls: “The order came: ‘Troopers advance!’ and the blue-uniformed line tore into the marchers’ orderly columns. Troopers bludgeoned the marchers with clubs, nightsticks, and whips, felling the unarmed activists to the ground. Then, as tear gas bombs were set off, the mounted men spurred their horses forward, trampling fallen bodies and lashing the retreating crowds with nightsticks. Over the screams and cries of the marchers could be heard the crazed whoops and cheers of white spectators waving Confederate flags.”

Goodwin continues: “Dozens were hospitalized with fractured skulls, arms, and legs, and scores more were receiving emergency treatment on-site.” Two days later, James Reeb, a white minister, and two colleagues were brutally beaten by white men shouting: “Nigger lovers.” Reverend Reeb died two days later, becoming another Selma martyr.

Where were the federal troops? Why didn’t President Johnson nationalize the National Guard? Protesters in Washington DC demanded that the president take action. But LBJ sensed that sending federal troops to Selma could endanger the passage of the Voting Rights Bill, since it could cause blowback from Southern white voters.

This impasse was resolved when Governor Wallace insisted on meeting personally with President Johnson in the White House. There he was subjected to the Johnson treatment, where LBJ persistently wheedled and cajoled his target into submission. Goodwin repeats their actual dialogue, which begins with LBJ showing Wallace photographs of police beating Black protesters on the Selma bridge.

LBJ: “Now that’s what I call brutality. Don’t you agree?

WALLACE: Yes, but they were just trying…

LBJ: Now, Governor, you’re a student of the Constitution. I’ve read your speeches and there aren’t many who use the text like you do.

WALLACE: Thank you, Mr President. It’s a great document, the only protection the states have.

LBJ: And somewhere in there is says that Nigras have the right to vote, doesn’t it Governor?

WALLACE: They can vote.

LBJ: If they’re registered.

WALLACE: White men have to register too.

LBJ: That’s the problem, George; somehow your folks down in Alabama don’t want to register them Negroes. Why, I had a fellow in here the other day” with a “PhD, and your man said he couldn’t registra because he didn’t know how to read and write well enough to vote in Alabama. Now, do all your white folks in Alabama have PdDs?

WALLACE: These decisions are made by county registrars, not by me.

LBJ: Well then, George, why don’t you just tell them county registrars to registra those Nigras?

WALLACE: I don’t have that power, Mr President, under Alabama law…

LBJ: Don’t be modest with me, George, you had the power to keep the president” “off the ballot.”

LBJ was referring to the last election, when Wallace had deleted Johnson from Alabama’s ballot. LBJ then asked Wallace to think about his legacy. Did he want to be remembered as someone who built something better, or rather as someone who just hated?

After this meeting, Governor Wallace agreed to request federal troops to help tamp down the violence at Selma, which meant that federal troops were not going to be seen as invading Alabama. Marchers marched across the bridge at Selma unhindered by State Troopers, and a few hundred activists were permitted to march to Montgomery, where they were again joined by the mass of protesters for the final leg of the journey to the state capitol.

Wallace later groused to the press, “Hell, if I’d stayed in that meeting much longer, he’d have had me coming out for civil rights!”

With this free television publicity from covering the Selma march, Lyndon Johnson was now ready to risk sending the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to Congress. On March 15, LBJ, on television, addressed both Congress and millions of Americans with the speech coined by Dick Goodwin:

“There is no Negro problem. There is no southern problem. There is no northern problem. There is only an American problem.”

“There is no moral issue. It is wrong, deadly wrong, to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country. There is no issue of states’ rights or national rights. There is only the struggle for human rights.”

“There is no cause for pride in what has happened in Selma.” “But there is cause for hope and for faith in our democracy in what is happening here tonight. For the cries of pain, and the hymns and protests of oppressed people, like some great trumpet, have summoned into convocation all the majesty of this government of the greatest nation on the earth.”

“The real hero of this struggle is the American Negro. His actions and protests, his courage to risk safety and even to risk his life, have awakened the conscience of this nation.” Then Johnson repeated the refrain so often used by Martin Luther King: “We shall overcome!”

Johnson had instructed Dick to include in his speech his personal story, which explained why he felt so deeply about the Great Society legislation. “My first job after college was as a teacher in Cotulla, Texas, in a small Mexican American school.” “My students were poor and often came to class without breakfast, hungry. And they knew, even in their youth, the pain of prejudice. They never seemed to know why people disliked them. But they knew it was so, because I saw it in their eyes. I often walked home later in the afternoon,” “wishing there was more that I could do.”

LBJ continues: “Somehow you never forget what poverty and hatred can do when you see its scars on the hopeful face of a young child. I never thought then, in 1928, that I would be standing here in 1965. It never even occurred to me in my fondest dreams that I might have the chance to help the sons and daughters of those students and to help people like them all over this country.”[4]

VIETNAM AND RIOTS THREATEN THE GREAT SOCIETY

Johnson’s administration faced a fork in the road in July 1965. “Vietnam is getting worse by the day,” LBJ confided to Lady Bird. “I have the choice to go in with great casualty lists or to get out with great disgrace.” Goodwin recalls, “Despite Operation Rolling Thunder,” the massive bombing campaign of North Vietnam, “and the presence of 75,000 American troops, the Viet Cong forces had taken the initiative with large attacks on the South Vietnamese Army. The civilian government in South Vietnam had collapsed, its economy was in free fall. The time had come for a major decision about America’s commitment to South Vietnam.” Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara recommended sending in an additional 300,000 troops to Vietnam.

LBJ told Goodwin, “I could see and almost touch my youthful dream of improving life for more people and in more ways than any other political leader, including FDR. I was determined to keep the war from shattering that dream, which meant I simply had no choice but to keep my foreign policy in the wings. I knew the Congress as well as I know Lady Bird, and I knew that the day it exploded into a major debate on the war, that day would be the beginning of the end of the Great Society.”

There were some domestic triumphs left. Johnson decided to move the signing ceremony for the passage of the Medicare bill, establishing federal health insurance for the elderly, to Independence, Missouri, so the elderly former President Harry Truman could witness the signing, since he had begun the battle for national health insurance so many years ago.

Goodwin recalls, “Life expectancy would increase, and infant mortality would decrease through Medicare and Medicaid. Segregated hospitals would vanish from the South once the government made clear that hospitals requesting Medicare funds” could no longer exclude blacks. Head Start programs would ensure that low-income children would be fed at school, and immigration reform ended a quota system that favored white immigrants.

Segregated hospitals caused many unnecessary deaths of Blacks after Reconstruction. In the Souls of Black Folk, WEB DuBois, co-founder of the NAACP, tells us how his first-born son died from diphtheria because the white hospital in Atlanta refused to admit black patients.

WEB Du Bois: The Souls of Black Folk, Personal Essays From Reconstruction Era

http://www.seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/web-dubois-souls-of-black-folk-fighting-for-dignity/

https://youtu.be/x212gx1lNIA

Pressure generated by Martin Luther King’s protests demanding black suffrage at Selma, Alabama, finally enabled Johnson to push the Voting Rights bill through Congress. Johnson chose to sign the bill in a ceremony in the halls of Congress, a tradition that had ended with Herbert Hoover.

LBJ delivered a short lyrical speech:

“Today is a triumph for freedom as huge as any victory that has ever been won on any battlefield.

Yet to seize the meaning of this day, we must recall darker times.

Three and a half centuries ago the first Negroes arrived at Jamestown.”

“They did not arrive in brave ships in search of a home for freedom.”

“They came in darkness, and they came in chains.”

“It was only at Appomattox, a century ago, that an American victory was also a Negro victory. And the two rivers, one shining with promise, the other dark-stained with oppression, began to move toward one another.

Yet, for almost a century, the promise of that day was not fulfilled.

Today is a towering and certain mark that in this generation, that promise will be kept.”

But five days later, serious riots erupted in the black neighborhood of Watts in Los Angeles. Dozens were dead, a thousand injured, and hundreds of buildings were looted and burned. Both Lyndon Johnson and Martin Luther King were devastated.

But LBJ was also sympathetic. “You have no idea of the depth of feeling of these people.” “They have absolutely nothing to live for, forty percent of them are unemployed.” “We have just got to find a way to wipe out these ghettoes and find some housing and put them to work.” But many whites who witnessed these riots in living color on their black and white televisions were not sympathetic.[5]

During the summer of 1965, Dick composed for Johnson his wishful Guns and Butter speech.

“This nation is mighty enough,

its society is healthy enough,

its people are strong enough,

to pursue our goals in the rest of the world

while still building a Great Society at home.”

Goodwin remembers: “Reviews of the speech noted a disquietude, a sense that something was out of joint. While liberal papers applauded the promise to sustain and even expand the Great Society, they were disconcerted by Johnson’s emphatic pledge ‘to give our fighting men what they must have; every gun, every dollar and every decision, whatever the cost or whatever the challenge.’”[6]

American involvement in Vietnam escalated, by January 1967, the troop levels had surged to 435,000 troops. Although more bombs were dropped on Vietnam than World War II and the Korean War combined, these bombs did not diminish North Vietnamese resolve or capacity to fight.

Democrats lost seats in the midterm elections, and Johnson could not thwart a Senate filibuster blocking a third major civil rights bill outlawing discrimination in the rental and sale of housing. Enthusiasm for civil rights was fading. Robert Kennedy called for a bombing halt so peace negotiations could begin. Johnson was devastated when Martin Luther King publicly opposed the Vietnam War in April 1967. The break with administration was permanent, LBJ and Martin Luther King would never meet again.

Martin Luther King & LBJ: Great Society, Vietnam, Chicago & Memphis, Lewis Biography Chapters 10-12

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/martin-luther-king-lbj-great-society-and-vietnam-northern-civil-rights-biography-chapters-10-12/

https://youtu.be/IeKssG8mrlk

Soon after Dick left his position as Johnson’s speechwriter to work for Robert Kennedy, Doris joined the White House staff as a Harvard intern. She almost did not get the job because she was co-author of her first published article in the New Republic, in which the editor attached the misleading title: HOW TO REMOVE LBJ IN 1968. Her selection as a White House intern was reconsidered after this article appeared. But after talking to Doris, LBJ thought she had been framed, and offered her the position, telling his staff: “Bring her down here for a year, and if I can’t win her over, no one can.”[7]

LYNDON JOHNSON DROPS OUT OF PRESIDENTIAL RACE

By the end of March 1968, LBJ’s approval rating had dropped to 36 percent, the lowest level of his presidency, and only 26 percent supported his handling of the war. His generals recommended committing another 200,000 troops, but he knew that the North Vietnamese would simply match the increase. The massive bombing was ineffective. How could America break this stalemate?

Johnson told his speechwriter, “I want out of this cage.” To break the stalemate, Johnson delivered a televised speech addressed to all Americans: “Tonight I want to speak to you of peace in Vietnam,” offering to “stop the bombardment of North Vietnam unilaterally.” If Hanoi responded, he would withdraw American forces as Hanoi withdrew its forces to the North.

Then Johnson stunned America further. “With America’s sons in the fields far away, with America’s future under challenge here at home, I do not believe I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties other than the awesome duties of this office, the Presidency of your country.”

“Accordingly, I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president.”

FAIR HOUSING ACT PASSED AS CIVIL RIGHTS EFFORTS SLOWED

Johnson told Doris Kearns that now his office could concentrate on accomplishing as much as they could to further civil rights without the political distractions in the remaining time of his presidency. About that time, against the advice of his advisors, Martin Luther King was planning another march on Washington. Perhaps there could be a reconciliation with Lyndon Johnson now that he committed to leaving Vietnam.

April 4, 1968, started as a hopeful day. The day before the White House had received news that Hanoi was ready to talk. Discussions with UN Secretary-General U Thant on peace in Vietnam were hopeful. But that evening, Johnson was handed a short bulletin: “Martin Luther King has been shot.”

Riots erupted immediately across the country. Calls were made by the White House to mayors and governors in vain to reach out to poor Black neighborhoods. Riots erupted in hundreds of cities, even a few blocks from the White House. Americans saw on their television sets scenes of lawlessness: bricks were thrown through store windows, there was rampant looting and fire and flames everywhere, and buildings were burnt to the ground. On the next night, thousands of troops were patrolling the streets of the Capitol.

In the wake of this assassination, enough goodwill remained for Lyndon Johnson to succeed in enacting the Fair Housing Bill, the third and last great Civil Rights Bill of his administration, “outlawing discrimination in the sale and rental of 80 percent of America’s homes.”

But there would be no celebrations, Johnson would not deliver a speech to a joint session of Congress. As Goodwin recalls: “A canvass of congressional opinion had made clear that the riots had turned compassion for Martin Luther King’s death into bitterness and fear. The public was in no mood to hear about massive programs for the inner cities.”

RFK ASSASSNATED, NIXON NARROWLY WINS PRESIDENCY

Due to his unpopularity, Lyndon Johnson stayed out of the Presidential race. Then prior to the Democratic Convention, the nation was again in shock when the frontrunner, Robert Kennedy, was shot. Goodwin remembers, “Dick had often said that for him, the Sixties came to an end that day.”[8]

Antiwar riots erupted at the Democratic Convention. The unending riots enabled Nixon to paint the Republican Party as the party of law and order. Johnson disappointedly canceled his plans for a dramatic entrance, there were fears that his attendance would spark more protests and violence. Instead, he watched the Democratic Convention on television from his Texas ranch. Hubert Humphrey, the Democratic nominee, distanced himself from Johnson to enhance his standing in the polls. Both South and North Vietnam backed out of peace talks, it was suspected and recently confirmed that this was due to illegal meddling by the Nixon campaign staff.

Nixon won a close election. Goodwin recalls, “Nixon won the election with 43.4 percent of the vote; Humphrey received 42.7 percent, Wallace 13.5 percent,” although the electoral count was 301 for Nixon, 191 for Humphrey, and 46 for Wallace. “With such a narrow margin, ‘the outcome would have been different,’ Johnson was convinced, ‘if the Paris peace talks had been in progress on Election Day.’”[9]

DISCUSSING THE SOURCES

We enjoyed reading the Goodwins’ recollections of how the Great Society was birthed in the momentous decade of the Sixties. With John F Kennedy, there was hope for the future, but after his assassination, under Lyndon Johnson, there was action, as he skillfully passed much of the Great Society and Civil Rights legislation. We did not discuss Dick Goodwin’s contributions to the campaigns of Robert Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy, nor did we cover the dramatic events of the Democratic Convention. Doris also recalls how Dick wrote the concession speech for Al Gore when he lost the 2020 Presidential Election when the Supreme Court ordered that the Florida ballots should not be recounted.

We have a more in-depth discussion of our sources on our first reflection on their memories of John F Kennedy’s administration.

John F Kennedy, Cuba, Russia, and Civil Rights, Book Review of An Unfinished Love Story

https://seekingvirtueandwisdom.com/john-f-kennedy-cuba-russia-and-civil-rights-review-of-an-unfinished-love-story/

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doris_Kearns_Goodwin

[2] Doris Kearns Goodwin, An Unfinished Love Story (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2024), Chapter 6, Kaleidoscope, pp. 150-166.

[3] Doris Kearns Goodwin, An Unfinished Love Story, Chapter 7, Thirteen LBJ’s, pp. 182-203.

[4] Doris Kearns Goodwin, An Unfinished Love Story, Chapter 8, And We Shall Overcome, pp. 209-234.

[5] Doris Kearns Goodwin, An Unfinished Love Story, Chapter 9, The Never-Ending Resignation, pp. 247-256.

[6] Doris Kearns Goodwin, An Unfinished Love Story, Chapter 10, Friendship, Loyalty, and Duty, pp. 271-273.

[7] Doris Kearns Goodwin, An Unfinished Love Story, Chapter 10, Friendship, Loyalty, and Duty, pp. 296-307.

[8] Doris Kearns Goodwin, An Unfinished Love Story, Chapter 11, Crosswinds of Fate, pp. 330-358.

[9] Doris Kearns Goodwin, An Unfinished Love Story, Chapter 12, Endings and Beginnings, pp. 364-372.

2 Trackbacks / Pingbacks